Sailing With Artist Charles Ray

05.01.06

Charles Ray’s modest house is a stone’s throw from the Santa Monica Airport and the Marina on the west side of Los Angeles. A large ovular block of wood painted to look like a human eye peers out from a clutch of bougainvillea grown up and around the step path that leads you to the front door. Inside things are very simple, the decor is spare. A living room: small couch, coffee table, book shelf, desk. A kitchen: old gas stove, fridge, small formica-top table and a couple chairs. "We have a lot of coffee here," Charles says. "Espresso." We sit down at the kitchen table.

Charles Ray’s modest house is a stone’s throw from the Santa Monica Airport and the Marina on the west side of Los Angeles. A large ovular block of wood painted to look like a human eye peers out from a clutch of bougainvillea grown up and around the step path that leads you to the front door. Inside things are very simple, the decor is spare. A living room: small couch, coffee table, book shelf, desk. A kitchen: old gas stove, fridge, small formica-top table and a couple chairs. "We have a lot of coffee here," Charles says. "Espresso." We sit down at the kitchen table.

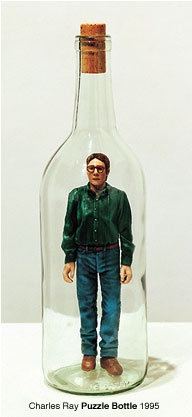

He doesn’t look much different than one of his mannequins or the numerous other self-portraits he’s shown over the years. Like No, or Yes: if you have seen those images, that is pretty much what he looks like, no big surprises. He doesn’t seem to have aged much at all since those were done. Bespectacled, with those ever wind-tasseled hyperborean locks, he’s dressed in a navy blue Polo t-shirt, blue jeans, and topsiders. A youthful, somewhat dowdy sailor, he brings his own microphone and plugs it into my dictaphone, playfully wielding it newscaster-style and asking me about how I edit interviews as we check that the thing’s recording.

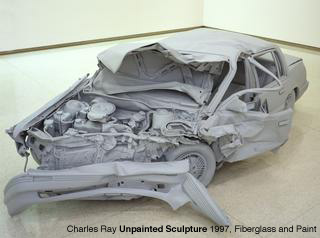

Ray’s work is at once majestic and sublime and really weird. But the quality that unbalances me is the meticulous, obsessive edge most evident in Unpainted Sculpture, the wrecked Pontiac Grand Am he took apart piece by piece, cast in fiberglass, and reassembled exactly over the course of years. His sculpture projects often take as much time and involve such painstaking attention to detail. And there’s the unrevealed labor, the many nuts and bolts hidden far inside the mangled car engine.

I figure there are multiple avenues to a discourse on an artist’s work, and the more oblique ones can be surprisingly revealing. A circuitous tack also eliminates the rote interview answers (and also celebrates the amateur in us all). So when I found out that Charles Ray was an avid sailor, I thought, this is a hobby that should give unique personal insight into the way this curious, scientifically engaged artist approaches his environment, consistently melding untamed natural beauty and hard physical mechanics. Thus sailing (with no divergence), was the term to which he agreed.

FANZINE: What was your first boat?

FANZINE: What was your first boat?

CR: My first boat was a Sabot—a plywood Sabot. A little eight-foot pram. Have you ever seen a Sabot?

FANZINE: No, I’ve never seen one.

CR: A lot of times they had that little Dutch wood shoe on the sail. They can be gaff-rigged. Mine wasn’t. They have a square bow. My father bought it for my brother and I when I was seven. We named it the Little Dipper. I named it the Little Dipper, actually. We used to go away in the summer. We lived in Chicago but we went up to Sturgeon Bay on the lake side. Sturgeon Bay is in Dorr County, Wisconsin. About seven hours north of Chicago. You’ve heard of the Green Bay Packers, the football team? They’re in Green Bay, which is on one side of Dorr County—Dorr is a long, narrow peninsula that divides Green Bay from Lake Michigan. Towards the top of the lake. Sturgeon Bay is on the Green Bay side of the peninsula. There’s a canal that goes from Sturgeon Bay out to Lake Michigan. So it’s shorter for ships going from Michigan or coming from the St. Lawrence to cut across the lake and go through the canal into Sturgeon Bay and then out down into Green Bay, which is a port. We had a cottage on the lake just south of the canal. About a half mile or so. We had been going to Wisconsin ever since I was really little. Then they moved cottages. My grandmother started renting this place on the beach in this region.

FANZINE: You’d go up for summers?

CR: We’d go up there during the summer. That was my mother’s family. My father’s family had another house at the very bottom of the lake in Indiana. At the Indiana Dunes. So sometimes the Little Dipper would follow us down there.

FANZINE: Did your father teach you how to sail?

CR: Mmm…Yes—the preliminaries. He didn’t sail too much but he got this boat for my brother and I and taught us the basics. And then we took sailing classes as well. I loved the boat. It was a beautiful little boat. White with a plywood interior. We could take the mast out, of course, and row. Which we did.

FANZINE: Does your brother still sail?

CR: Yes, he’s a very good sailor.

FANZINE: When you were a child did you have sailing heroes?

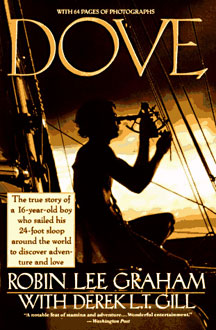

CR: Later. Not when I was seven. But later. Like Robin Lee Graham, who sailed the Dove around the world. Do you know him? Have you seen his pictures?…Let me grab that book.

Charles leaves the room and soon returns with a copy of Dove by Robin Lee Graham.

CR: This morning Silvia told me sailing interviews are always the same. She said there’s always a big wave and a woman that crawls into the bunk. So I’m hesitant about—there’s never been a woman—I’m hesitant about the big waves.

FANZINE: Yeah. (laughs)

CR: (laughs) Or the disasters.

FANZINE: Right. I wouldn’t worry too much about it. So this is his book?

CR: Yeah. It’s quite beautiful because after all of that—sailing around the world and meeting his bride and the disasters, all when he was a teenager—it’s just a wonderful story. Why his parents ever let him do it I never figured out. But after all that he comes back and he stops sailing. You see, he became a hippie—a kind of born-again hippie. And he moved to Colorado with his family.

FANZINE: This was in the sixties, right?

FANZINE: This was in the sixties, right?

CR: Yeah, it was in the sixties. And then, it was quite beautiful because later when I first moved to Los Angeles I bought another boat about the size of the Little Dipper—just a little bit bigger. A nine-foot boat. I named it the Tea Spoon. Another beautiful little boat. I used to sail it out of the marina, out into the ocean. I fished off of it. Just had a great time with it. Then I bought a San Francisco Pelican that was about two-thirds finished. I completed that and sailed her around for a little bit. That was another twelve-foot boat. But very beamie and a very sea-worthy little ship. Then I wanted to go farther—be able to go off-shore and go off to the islands and whatnot. I bought a Lapworth 24 for $3,000, an old beater that was for sale up in the Channel Islands. It had a very beautiful hull shape—really beautiful. That turned out to be hull number one of the Lapworth 24’s—one of the first fiberglass boats to be made, I think around ’57. Lapworth was a great designer. He designed the Cal 40. One of the early people to start designing fin keels. His was the hull number one of the Lapworths. And Graham’s boat, the Dove, was a Lapworth 24. So I was quite happy with that. But his wasn’t as pretty as mine. I wish I had a picture of the old Glass Slipper. It had a larger cabin top. The first one, its cabin was much smaller—one window and much more sporty. Almost like the new C-Squared.

FANZINE: So were you and your brother following this story of Robin Lee Graham? I’m trying to figure out exactly when this was…

CR: I don’t know that we followed it as it happened. But in and about there we got a hold of National Geographic at some point and it had his story. It was wonderful. It was quite inspiring. We all wanted to be him.

FANZINE: Right.

CR: Standing at the back of the boat taking sextant sights and whatnot.

FANZINE: In the way that other kids would want to be Mickey Mantle?

CR: Yes, but I think that there was already kind of a lifestyle envy or something. You see this guy in his shorts and t-shirt, he’s sixteen years old, and, you know, “Why can’t I have parents like that?” (laughs) Even though it was beyond comprehension that this guy could go off at sixteen, and maybe it still is a little bit, but his parents said, “Yeah, it’s cool. We’ll help you fix the boat up.” And National Geographic went along with it and funded it and followed him from port to port.

Commodore Tompkins pointed something out to me, a good thing for all sailors to realize. That everything in a boat is inter-related. If you take a boat and you go cruising with it and load it down, it sinks deeper into the water. So it not only makes it a little slower, but it makes it a little stiffer. Meaning it doesn’t tip as quickly. So if it tips at, say, twenty degrees in fifteen knots of wind, it might not heel to twenty degrees in twenty-two knots of wind. The wind doesn’t spill out of the sail quite as quickly because the boat is stiffer. But the rigging is set for the way the boat was originally designed to sit on its lines.

A couple of times Graham was loaded down for cruising and the one thing he hadn’t thought of in the preparations was to increase the size of the rigging. And thus he broke stays. I broke a couple stays on my Lapworth too, but the mast was actually carried away on him twice.

FANZINE: So was that an embarrassment to him?

FANZINE: So was that an embarrassment to him?

CR: Well, I don’t think so. He was a kid.

FANZINE: To the designers?

CR: No, no, no. I think it just was part of the adventure. Mine leaked like a sieve at the hull-deck seam, too. I was always trying to fix the leaky deck on mine. And I was quite pleased when I went back and saw that he had the same problem. He was always re-caulking that hull-deck joint. Really a beautiful boat, though. Do you like the name, The Dove? Maybe?

FANZINE: Well, for—

CR: For him it was good. Maybe because of love.

FANZINE: Do you like the name?

CR: Yeah, yeah, I kind of do. How about this picture (shows a picture of Robin Lee Graham topless playing the guitar)? That was in National Geographic.

FANZINE: (laughs) That’s great. So you liked his story for the fantasy. For the adventure.

CR: Yeah, I occasionally have found, every time I go into an old bookstore—you know, a really crazy bookstore that is full of old mildewing things and has stacks of magazines in the back—if they have National Geographic, I always look for those issues. I had them for a few years then gave them away.

FANZINE: Do you throw everything out every couple years?

CR: Yeah, I try to. Not everything, but…’65! See: "The morning of July 27th, 1965 was a marvelous one, with the sun burning off the mist of the outer harbor. Excitement killed my appetite, but I sat down with Judd Croft and ate a bowl of breakfast cereal. Joel Gibson, a girlfriend who’d come up from Newport delighted the cameraman by giving me a kiss. Then my father came aboard. He looked ill-at-ease, uptight, and when he put out his hand I noticed it was crumpling. He said something about seeing me in Hawaii. Then exactly at ten o’clock, I started up Dove‘s inboard engine. That was the beginning of it all." Let’s see the chapters: "Loneliness and Landfalls". "Love and Blue Lagoons". That must have been before the movie Blue Lagoon—yeah, ’65. This is (points to picture of Robin Lee Graham’s boat, Dove) kind of the size of the Little Dipper.

FANZINE: Can I take a picture of that? Tell me if I take too many pictures.

CR: No, you can take as many as you want.

FANZINE: (Takes picture) That’s great.

CR: Maybe you should take a picture of him playing the guitar.

FANZINE: Yeah. (Takes picture) Was everyone so taken by his story—the whole country?

CR: No, I don’t think the whole country. I was, really. But, I mean, my God… I thought it was really easy to fantasize, to project yourself into his place. Just the whole aspect of…leaving. Getting on a boat, and being away from your parents. Boats, for me, were summer. You know? The lake. The waves. It was wonderful. There was some kind of legitimacy to it too. His parents let him do it. My parents wouldn’t even let me take the train and go to the other side of the city for the weekend and visit my girlfriend.

CR: No, I don’t think the whole country. I was, really. But, I mean, my God… I thought it was really easy to fantasize, to project yourself into his place. Just the whole aspect of…leaving. Getting on a boat, and being away from your parents. Boats, for me, were summer. You know? The lake. The waves. It was wonderful. There was some kind of legitimacy to it too. His parents let him do it. My parents wouldn’t even let me take the train and go to the other side of the city for the weekend and visit my girlfriend.

FANZINE: So what happened when you went to military school—with sailing?

CR: Well, I wasn’t there in the summers. I’d go home in the summer so I could still sail. was the happiest on the beach when I was a kid at my grandparents’ summer houses. It was just wonderful to get on boats and go swimming and poke around and do beach kinds of things. You know, I was more popular with kids in the summers on the beach. I wasn’t so popular in grade school because I wasn’t into sports and I wasn’t that good academically. So leaving all that behind and stepping into the world of the beach was a different thing, because it wasn’t baseball or school. It was more swimming or body-surfing, messing around with the boats and sand-surfing and these kind of things.

FANZINE: But with sailing, there’s the solitary aspect to it as well.

CR: Well, when we were little, not so much. Yeah, you’d go off by yourself. It was solitary, but there’s always that wonderful… you know, there’s a kinesthetic joy to it that runs through the body when you’re moving in a boat. Catching waves, or you’re heading up-wind. That appealed to me when I was a youngster, too. You know, incremental steps or senses of adventure. I was scared, too, when I was kid. Going out too far, and big waves, and tipping over. It was a scariness that also draws you into it.

FANZINE: Did you have any traumatic crashes or anything?

CR: Many over of the years. Many, many, many.

FANZINE: When you were a kid?

CR: Many, yeah. A few. They almost lost me in the Little Dipper the first or second year we had it.

FANZINE: What happened?

CR: Well, my father wasn’t there during the week. The fathers would only come to these summer houses on the weekends. Which was great. You’re just there with the cousins and the aunts and the grandmas and your mother. In Sturgeon Bay we had two cottages—two houses right next to each other. It was just an enchanted place. The houses were on a tiny hill––just a driveway’s length––and there was a dirt road and a very small bluff––maybe fifteen feet high, with trees on it––and then it angles down into a very long beach. Maybe forty yards, fifty yards––a big beach. And then a mile to the north you could see the breakwater for the canal and the lighthouse.

But the disaster: My father got a hold of an old buoy. Not a very big one––for fishing nets or something––and got some cement blocks and put it what I thought then was about a block out. I put everything in terms of blocks––twenty blocks, ten blocks––instead of yards or miles. So he put it about a block out and said, “Never go past these buoys, boys. That’s the one rule.” And he gave us another rule. He said, “If anything ever happens, you stay with the boat.” It was just hammered into me, before I ever got in a boat. “Stay with the boat, stay with the boat.” And he put this buoy out. And I got out one morning before anyone else got up. Maybe this was the first year we had the boat. There was a stiff off-shore breeze blowing. Most of the winds up there were off-shore because it’s on the Wisconsin side––the westerlies come across. There was a good breeze blowing and it’s very easy to sail down-wind, right? It’s harder to come back against the wind. I pulled the Little Dipper down to the beach, rigged it up. I drag it into the water and off I go.

At the canal there was a red buoy you could always see and it was very small. For some reason I thought I’d go check that buoy out. It was two and a half or three miles outside of the canal. It was the marker for big ships to turn––so they wouldn’t run aground. I got out there and by then it was wavy. It isn’t very wavy when you’re in close because there’s no fetch, but at two and a half miles out it was quite windy and choppy. I remember looking at this buoy. And it was huge. And I got really scared because it was so big. And it had ladders on it and hatches—you know, like submarine hatches with the big wheels on them that you could open, water-proof hatches. It was like two stories tall with ladders and a big red blinking light and a huge number on it. And I thought, “My God, what have I done? What in the world have I done?” It was so foreign to be out there next to this big weird object. I kind of knew instantly, just by the nature of the object, that I shouldn’t be there. I shouldn’t be seeing this big thing with these rivets on it. I should be looking at little ply-wood boats or something. This is big and red with rust streaks on it and waves smashing up against it. It was so windy that I swamped the boat. It filled with water and tipped half over and looked really low on its lines. I was just petrified. I kind of gathered up the sail, sort of tied it a little bit, and put the oars in the oar locks. I was going to try to row in this swamp boat. It was so low in the water that the first wave that came knocked the oars out of the oar locks. I just watched them drift away.

So there I was, sails flapping, drifting. It was too deep for the anchor to touch. I took out the ropes that I had, like the sheet and whatnot, to extend the anchor. I think it slowed it down, but it didn’t catch.

At a certain point—it must have been 7:00 or 7:30 by now—I saw a kid on the beach. He looked so small, like an ant. He had a little soccer ball he was kicking. And seeing someone on the beach, made it seem so desirable to not be on this boat. This is early June, and in Wisconsin the water’s very, very cold. So I decided to swim for it. I dove out of the boat. I was, I don’t know, seven and a half, eight. And I started swimming two and a half miles through twenty-knot, fifteen-knot off-shore breeze with waves and ice-cold water. I got—and again, there’s this distance thing—what I thought was about two blocks from the boat, and my dad’s voice started ringing in my ears: “Stay with the boat… Stay with the boat.” So I thought, “That’s a good idea!” So I turned around, I swam back to the boat, and somehow I skimmed up into it. What I remember most when it first happened was peeing in my pants. Then I remember, after I got back in the boat, praying, "Hail Mary, full of grace, Hail Mary, Hail Mary," over and over. Then eventually people got up and came down to the beach at 8:00, 8:30 and started saying, “Where’s Charles? Where’s the boat?” They saw the little sail out there, flapping, just half-up. You could barely see it. They called the Coast Guard and my mother got a hold of somebody else with a motorboat. Both the Coast Guard and the motorboat converged on me. It must have been 8:30, 9:00. As they were approaching the speakers started blasting, “Stay with the boat! Stay with the boat!” (laughs) So I was rescued.

FANZINE: You were out there for a good hour?

FANZINE: You were out there for a good hour?

CR: Hour and a half, maybe two hours. That’s probably my most traumatic sea story. After that there are many spills and tip-overs and stuff, but…

FANZINE: What did it take to get you out on the boat again?

CR: That wasn’t really the issue. I mean, it wasn’t scary to go back out again. I never felt that I was dying or going to die or something. It was more my mother. I think she didn’t tell my father. Or didn’t tell him until later or something…

FANZINE: The trauma was that you scared your mother?

CR: My mother was pretty scared. When you’re seven or eight, you don’t think you’re going to die, but I suppose it was traumatic to me. I certainly remember it quite clearly. I can’t quite remember what I was wearing, or what people were wearing—I don’t remember it photographically. More kinesthetically—I remember the wetness, the cold, the flapping, and the brightness of the sun on the plywood, on the sail, on the lines… it’s very vivid. And I think that’s what I like about sailing, the vividness.

It’s funny, when you sail off-shore, there’s an illusion there. If you haven’t gone off-shore, you look at a globe and you just see this big expanse of blue, so you think you’re in the middle of nowhere. But I always had this feeling that you are specifically somewhere. I have this very strange illusion always that I’m sailing in a fjord, up against a wall—that I’m really in a geographical location. I think it has to do with clouds and cloud formations and stars and stuff like that. I always feel like I’m really not in the middle of nowhere, but somewhere very specific. Geographically. Even though there’s no land. It’s a funny feeling.

FANZINE: I think that most people would, when you’re solo sailing out in the middle of the ocean, have a fear of—

CR: I’m not always solo. I like to sail solo a lot. When I went to Hawaii I went with a crew, which I was happy about. But it’s not so lonely…Well, I guess it’s lonely. It can be lonely. Scary lonely, maybe, less lonesome lonely.

FANZINE: You feel alone.

CR: Yeah. But it’s nice to feel alone sometimes too, huh? If you’re in a race with other people who are sailing alone, that’s nice. You don’t see them per se, but you’re with a group. You’re all doing something but you don’t have to put up with each other’s company. But you’re still being social, right, because you’re racing against these other guys, and checking in on radio every six hours. So there’s still this civilized or social gathering.

FANZINE: But this is something that interests me, because in that Dennis Cooper interview in Index you say that sailing is like “instant wilderness.”

CR: That’s true, yeah.

FANZINE: You were talking about the psychedelic, a narcotic experience, and making a correlation there.

CR: That may have been exaggerated, to… just a way to do an interview or to talk. Oh, I remember what that was about! I think to compare it to the psychedelic was a little bit pumped-up. You know, a little show-offy maybe. But it’s similar in that if you were taking acid and things got rough, you can’t just say, “Okay, that’s enough. I want to come down.” It doesn’t work that way. Sailing’s kind of similar. If you’re out off-shore or coming down the West Coast you can’t just say, “Okay, I want to get off the boat now.”

FANZINE: “Stay with the boat.”

CR: Yeah. You can’t just say, “I’ve had enough.” The west coast of California can be quite windy from southern Oregon to Mendecino. It’s awesome, really. For me anyway. You have to pay attention. It can be stormy, scary, and really blistery with big waves and stuff. And there’s nowhere to go. You can’t just say, “This is too much.” You could be 60 miles off or 100 miles off and you just have to keep doing it.

CR: Yeah. You can’t just say, “I’ve had enough.” The west coast of California can be quite windy from southern Oregon to Mendecino. It’s awesome, really. For me anyway. You have to pay attention. It can be stormy, scary, and really blistery with big waves and stuff. And there’s nowhere to go. You can’t just say, “This is too much.” You could be 60 miles off or 100 miles off and you just have to keep doing it.

FANZINE: And you like that.

CR: Well…

FANZINE: Some people, I think, would see that as a deterrent. Like the acid metaphor, it’s the bad trip.

CR: Yeah, but you can’t.

FANZINE: And that attracts you.

CR: Other things do too, though. Sailing’s kind of delayed gratification. It’s experiential. I think it’s safer than it seems. It seems scarier than it really is. To see a nice developed sea-way, it’s awesome. Majestic is the word. Coming down the West Coast it can be very, very windy. But not storming. It can be blowing 35, 40 knots, and not a cloud in the sky. So you have all these breakers as far as the eye can see. Just tumbling. Maybe 10-, 15-foot seas breaking all around you. Charging down, one wave after another. It can be scary. It’s just an awesome, majestic environment. Nature. You don’t have control over it.

FANZINE: So it’s like coming up against, interacting with a force as powerful as nature—it’s a power you have to reverence.

CR: Yeah. It’s not like coming up against a force, like there’s so many forces to choose from. It’s just experiential. It’s challenging. But it’s not all like that. A lot of it is just boring, quiet and stuff. It just feels good.

FANZINE: It’s that poetic thing. People talk about a man’s relationship with a horse. There’s something about that interaction. It’s not harnessing this force, but finding out how to integrate yourself into it.

CR: Yeah. Like if you know how heavy a bathtub full of water is and you start looking at waves, you kind of get awe-inspired by the power of the sun. Because it’s the solar energy moving all this water across the ocean. You can’t stop it. There’s a beautiful, fairly romantic quote about the ocean. Something like, “If you think the ocean is malevolent, or if you think the ocean is benevolent, you’re wrong. It simply doesn’t know you’re there.” That’s really beautiful. It doesn’t know you’re there. To be somewhere where you don’t matter. It’s not out to kill you; it just doesn’t know you’re there. So it’s not like you’re up against it.

FANZINE: You just find your way through it.

CR: You find your way through it.

FANZINE: You okay?

CR: Yeah I’m fine. Maybe we’ll get more coffee.

FANZINE: Is this the kind of thing that’s okay to talk about?

CR: Oh, yeah. We can go on for days. I’m fine.

(Sound of Charles getting coffee, pouring it.)

CR: Sailing, for me, it’s very rich. It’s always been my passion as a hobby. I really like doing it.

FANZINE: Has there ever been a time when you didn’t sail for an extended period?

CR: Yeah, and there are times when I don’t sail as much as other times. I’ve used it to… really just to get away. I’m a good sailor, not a great racer. I’m not like these people who have devoted their whole lives to it. I don’t think I could see doing that. In fantasy maybe. Can’t see living on a boat. I’m not really interested in cruising. I like making passages and sailing off-shore. Racing’s really nice. I like the competition, I’m a pretty competitive guy. Also it’s just an excuse to go sailing. It gives you a destination. I guess I like solo sailing because in some ways it’s a little less competitive. It’s almost like performance cruising a little bit. My group that I race with, you can kind of find your own level. And if you lose—and I lose plenty of races—you’ve still done the course by yourself. You’ve gone out and sailed 400 miles or something by yourself, you have that sense of accomplishment. Which probably people should anyway no matter what they do.

FANZINE: What is the social dynamic like when you’re out on these trips? Like the Hawaii trip.

CR: Well, people have to kind of slot in. You have to figure out what personality is what, you know, let the macho people be macho, in order for everyone to get along. You have to figure out everyone’s personality. It’s like being in this kitchen for two weeks or something. But if the weather is nasty, it’s really nice sometimes to be with people who know what they’re doing. I was really happy to go to Hawaii with five guys that first time. You kind of learn the way there. Maybe next time I’ll do it double-handed. And then maybe the third time I’ll do it single-handed.

FANZINE: Do you think that, with this competitive aspect of sailing, you channel all your competitive spirit into sailing? Are you competitive in other things?

CR: I’m probably pretty competitive. I don’t really recognize it. People say, "You’re so damn competitive," or something, so…

FANZINE: So you guess you are.

CR: Yeah. I always feel it’s good-natured.

FANZINE: Healthy.

CR: Healthy.