When Marina Abramovic Dies

12.05.10

When Marina Abramovic Dies is a biography of the Serbian-born artist written by her former assistant, James Westcott. The author’s first job for Abramovic was to painstakingly transcribe video tapes of The House With The Ocean View (2002), a performance in which Abramovic lived on-view in a gallery for twelve days. Westcott wrote down everything she did in those seventy-two hours of footage: sleeping, sitting, standing, drinking, urinating. Westcott’s biography performs another function for the artist, making a case for Abramovic’s contribution to the last four decades of art history by presenting her live art and life story in prose. The book suggests that in order to become sacred, one must tend to one’s own mythology: it is titled after Abramovic’s proposed final performance, her funeral, which requires three coffins be buried on three separate continents. And Antony and the Johnsons will sing. Writing with a former employee’s insight, Westcott appears an acolyte preemptively eulogizing his master.

When Marina Abramovic Dies is a biography of the Serbian-born artist written by her former assistant, James Westcott. The author’s first job for Abramovic was to painstakingly transcribe video tapes of The House With The Ocean View (2002), a performance in which Abramovic lived on-view in a gallery for twelve days. Westcott wrote down everything she did in those seventy-two hours of footage: sleeping, sitting, standing, drinking, urinating. Westcott’s biography performs another function for the artist, making a case for Abramovic’s contribution to the last four decades of art history by presenting her live art and life story in prose. The book suggests that in order to become sacred, one must tend to one’s own mythology: it is titled after Abramovic’s proposed final performance, her funeral, which requires three coffins be buried on three separate continents. And Antony and the Johnsons will sing. Writing with a former employee’s insight, Westcott appears an acolyte preemptively eulogizing his master.

Westcott took Abramovic’s boot camp-style “Cleaning the House” workshop in rural Andalusia, and was subjected to five days of fasting and total silence during which “reading, sex and cell phones were also forbidden.” The author engaged in exercises, standing naked and blindfolded in the hot sun while being photographed for the Abramovic archive, enduring forced staring contests with the other participants, “trying to live up to Abramovic’s example, after all.” In writing about Abramovic’s method of teaching her “transcendental strain” of performance art, the writer ponders the question, “Why were we doing this?” Tellingly, it is the one question Abramovic instructs her students not to ask. The answer for Westcott may be found in a passage in which the author describes Abramovic’s effect on the Dutch art circle that embraced her in the 1970’s: “Marina’s charisma beguiled almost everyone she met. She was also capable of absorbing enormous amounts of dedication…it was an exhilarating and blessed place to be, bathed in Marina’s aura.”

If Westcott has a tendency to inflate Abramovic’s “aura,” it is motivated by the subject herself. At the age of twenty-seven, Abramovic asked a prominent curator, “Am I still young and beautiful enough to become a famous artist?” The answer is still “yes”. Suddenly omnipresent in a media obsessed with the nude bodies on display in her MoMA retrospective, one may wonder when Abramovic’s long sought apotheosis occurred. According to Westcott, it was in 1997, when she won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. However, the world did not have proof until Seven Easy Pieces at the Guggenheim in 2005, when Abramovic “re-performed” the greatest hits of performance art. By adapting iconic performances by Vito Acconci, Joseph Beuys, Valie EXPORT, Bruce Naumann and Gina Pane (with permission; only Chris Burden vetoed a re-do of Transfixed), Abramovic transformed them into durational artworks, each lasting seven hours. With gold-leaf on her face, Abramovic is photographed also Explaining Pictures to a Dead Hare, for posterity. Two Abramovic pieces, one old and one new, were also presented in the week-long program. Thus, the artist asserts a canon of performance art history that places her oeuvre, and her body, at its center.

When Marina Abramovic Dies gives Abramovic’s narrative the full star treatment. Exciting descriptions of action-packed performances are accompanied by lots of pictures of nudity and self-inflicted violence. Sexy relationship drama takes center stage when Abramovic begins her twelve-year collaboration with the irascible Ulay, an eccentric German artist who provides an unforgettable foil for our heroine. A traumatic childhood complicated by Soviet Era politics fills the first few chapters with compelling tales of murky Eastern European histories and Oedipal tragedies. Later in the book, Westcott details the high-stakes financial dealings behind raising the hundreds of thousands of dollars needed to complete a performance in which Abramovic and Ulay walked the entire length of the Great Wall of China from opposite directions, meeting in the middle only to end their relationship (The Lovers, 1988). There is art world gossip too (she had an affair with Klaus Biesenbach). Throughout, Abramovic is written about like a foreign movie actress (she is described by video artist Charles Atlas as having a face fit for a close-up on the silver screen). Notably, quotations from interviews are reprinted without correcting her non-native English grammar. The author asserts that this communicates her story-telling style. Exoticized in her own biography, Marina Abramovic is willingly re-invented as a literary character.

When Marina Abramovic Dies gives Abramovic’s narrative the full star treatment. Exciting descriptions of action-packed performances are accompanied by lots of pictures of nudity and self-inflicted violence. Sexy relationship drama takes center stage when Abramovic begins her twelve-year collaboration with the irascible Ulay, an eccentric German artist who provides an unforgettable foil for our heroine. A traumatic childhood complicated by Soviet Era politics fills the first few chapters with compelling tales of murky Eastern European histories and Oedipal tragedies. Later in the book, Westcott details the high-stakes financial dealings behind raising the hundreds of thousands of dollars needed to complete a performance in which Abramovic and Ulay walked the entire length of the Great Wall of China from opposite directions, meeting in the middle only to end their relationship (The Lovers, 1988). There is art world gossip too (she had an affair with Klaus Biesenbach). Throughout, Abramovic is written about like a foreign movie actress (she is described by video artist Charles Atlas as having a face fit for a close-up on the silver screen). Notably, quotations from interviews are reprinted without correcting her non-native English grammar. The author asserts that this communicates her story-telling style. Exoticized in her own biography, Marina Abramovic is willingly re-invented as a literary character.

According to this book, the story of Marina Abramovic is one of supernatural determination, what Westcott deems her “will power.” The reader learns of this power early on, when two-year old Marina is witnessed sitting completely still for hours, next to a full glass of water, to the astonishment of her grandmother. It is this “will power” that makes possible Abramovic’s life-long project of devising endurance trials for herself, and her audience. In the Rhythm series of the 1970s, Abramovic subjected herself to self-mutilation and asphyxiation, provoking her audience to either torture her, or save her from herself. Abramovic’s uncanny endurance was first exploited in this masochistic (or “self-sadistic” as Westcott argues) vein of body art. The Rhythm series resembles the conceptual woundings of Burden and Pane, with the baroque flair of the Actionist’s ritualistic oeuvre. Ambramovic participated in a Hermann Nitsch performance in Vienna in 1975, and her work of this period used a related vocabulary. The difference lay in Abramovic’s engagement with both mythic and political associations. When she cut an inverted pentagram onto her stomach for a lover whose name was Thomas Lips (1975), the act may have evoked a magic spell, but when Abramovic lay surrounded by a flaming star until she lost consciousness in Rhythm 5 (1974), no one in the Belgrade audience overlooked the fact that she was being immolated by a symbol of communism.

Feminist projects, like Role Exchange (1976), in which Abramovic sat in a window in the Amsterdam red light district while a prostitute took her place at an opening at de Appel, gave way to a bodily confrontation with physicality when Abramovic teamed up with Ulay. The two wrote a manifesto for what they termed “Art Vital,” rules modeled on an idealized asceticism, in order to structure their aesthetics of reduction. Among the rules of Art Vital: “Permanent movement,” “Self-reflection,” “Passing limitations,” “Extended vulnerability,” and “Exposure to chance.” The regimen appears a reaction to the undifferentiated concepts of the self they encountered in their respectively Communist and Fascist childhoods. Tellingly, the strictures that proved most difficult to adhere to differentiated their work from theater: “No rehearsal,” “No predicted end,” and “No repetition.”

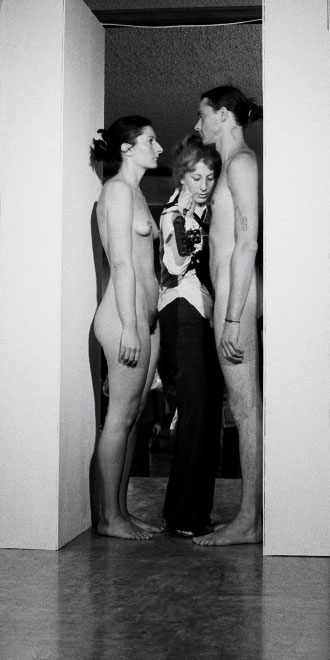

When Abramovic invited Ulay to the Venice Biennale in 1977, the post-minimalist attraction the two artists created was called Relation in Space. Westcott describes it like a romantic dream sequence: “The towering Ulay, taught and wiry without an ounce of wasted or suspended energy stored in him; Abramovic slim and nubile, with thick hair flowing majestically behind her as she ran.” The author adheres to a classical gendering of the artist’s bodies. Although Westcott notes that some feminist critics were disappointed by Abramovic’s decision to work with a man, he does not parse the gendered significations. While the performance art of this period is linked historically to the development of feminist art practices, that is not the critique readers will find here. Instead, we are given a heterosexual love story, one which ends when the artist-lovers take a fateful vow of celibacy, which they only honor with each other. Toward the end of their collaboration, the duo performed Nightsea Crossing (1984) ninety-nine times, staring at each other from across a table for several hours a day. Ulay developed a herniated disk; Abramovic thought his agony was psychosomatic.

Abramovic’s confrontation with physical limitation, compounded by the passage of time, becomes a metaphor for her longevity in the art business. When Abramovic was advised to wait for ten years to sell her archive, as its value was sure to go up significantly, she replied, “I am patient.” The collection of dramatic photographs crystallize this tension between the archive and the lived action. The body of work and the body of the artist were both passively resistant to, and profoundly affected by, the artistic climate which blew by her.

Westcott spends equal time contemplating Abramavic’s less popular works. After the break-up with Ulay, Abramovic turned to making sculptural furniture, embedded with crystals purported to have healing properties. A foray into a gallery career which occupied the late eighties and early nineties, these were incredibly expensive and did not initially sell very well. What people wanted from Abramovic was Abramovic.

Less predictably, Abramovic turned to theater during the early 1990’s, collaborating with Charles Atlas on a series of somewhat camp experiments in stagecraft. Reacting against the years of puritanism proposed by “Art Vital,” the two concocted projects such as Biography (1992), in which actors re-perform Abramavic’s iconic pieces, and Delusional (1994), in which the performer sits on a stage surrounded by fake rats. Westcott has misgivings about Abramovic’s relationship to the proscenium. Writing about an Abramovic-Ulay collaboration which occurred in the theater, he concludes,

It may have felt like the stage was the natural –

terminal –destination for their work… But in the

theater, all ethical conundrums were blocked by the

fourth wall. With performance art the only kind of

disbelief the audience had to suspend was the

feeling of how can they be doing that to themselves?

Westcott’s attempt to grapple with the institutional frame of the theater space points to what may have been a failure of the artists to activate their “ethical conundrums.” Clearly, many complex dilemmas have been successfully staged despite the dreaded fourth wall. That said, what may be lost in a theater space is the audience itself: the viewers, seated and out of view of one another, are off the hook, and it may be that this absence is what Westcott is alluding in marking the territories of “theater” and “performance art.” Yet, Westcott notes, “working in the theater answered some deep desires for Marina: for confirmed adulation.”

Inevitably, Abramavic becomes a celebrity. One need only compare photos from the beginning of the book to those at the end to see that she had plastic surgery, and the book does reveal that she had a breast augmentation in Brazil in the 90s. The book jacket quotes Bjork calling Abramovic’s work “iconic/monumental” and we are told that Abramovic hung out with the Icelandic pop star at her Guggenheim birthday party. Also: Antonyof Antony and the Johnsons was there. Obligatory in a bio, star-sightings are fairly irrelevant. What I enjoyed reading (and took notes on) was Abramovic’s focus on cultivating her connections with curators: when RoseLee Goldberg visited Abramovic at her home in Amsterdam, there was a candle-lit bath tub full of mineral water waiting for her. Westcott ticks off a list of curator conquests, from Chrissie Iles to Germano Celant. The book draws to a close in 2006 at Abramovic’s sixtieth birthday party, held at the Guggenheim, a photo of the artist looking younger than ever in custom Givenchy. Knowing, as the reader does, that the best is yet to come, the accounts of adulation for her successes read like prophecy.

————————————————————————————

image credits:

Marina Abramovic Nude with Skeleton. 2002-05, black-and-white photograph. © 2010 Marina Abramovic. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Marina Abramovic and Ulay Imponderabilia. Originally performed in 1977 for 90 min. Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna, Bologna

© 2010 Marina Abramovic. Courtesy Marina Abramovic and Sean Kelly Gallery/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Marina Abramovic Seven Easy Pieces. Performed in 2005 for seven consecutive days for seven hours each day at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Day six: Marina Abramovic, Lips of Thomas, originally performed for two hours in 1975 at Galerie Krinzinger, Innsbruck. Photo: Attilio Maranzano. © 2010 Marina Abramovic. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

–––––––––––––––––——————————————————–

Related Articles from The Fanzine

An Interview with Alex Segade and Malik Gaines of My Barbarian