The Haze Pervades: Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice

01.10.09

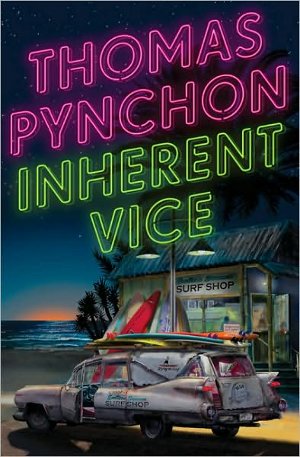

Inherent Vice

Inherent Vice

by Thomas Pynchon

Hardcover: 384 pages

Penguin Press HC

(August 4th, 2009)

––––––

‘Yeah, PIs should really stay away from drugs, all ’em alternate universes just make the job that much more complicated.’

—Fritz Drybeam, Inherent Vice

Did Thomas Pynchon write Vineland, the most cartoonish and tangential novel to carry his name? No. Or, perhaps more accurately, most Thomas Pynchons did not write Vineland. Likewise, it’s safe to say the Pynchon of Against the Day did not write Inherent Vice. Which of these Pynchons is responsible for this late, relatively breezy work? Inherent Vice bears some resemblance to Vineland’s countercultural fantasia, and is perhaps a distant cousin to his California-paranoia, shaggy dog story, The Crying of Lot 49. Nevertheless, all of these works take place in Pynchonia, an ever-expanding multi-verse that cannot be contained even in the weightiest of this oeuvre’s tomes.

Pynchon has always been a genre enthusiast, even as he tends to blenderize his registers. In this case, he shows us that a psychedelic detective story isn’t just colorized noir. Inherent Vice’s protagonist, Larry “Doc” Sportello, is a borderline narcoleptic private investigator approaching thirty, about the age Pynchon was at the dawn of the ’70s, when the novel is set. Prone to inopportune, dope-fueled fits of deep sleep, Doc routinely nods off to find himself in other worlds: some nostalgic, some fantastic, some auguring a bleak eternal recurrence.

Halfway through the neon dream of Inherent Vice, the lights go out and Doc is transported from hyper-colored ’60s to monochrome ’50s. Along the way, he undergoes an appropriate change of wardrobe, transforming from a hippie-fro’d and pizza-stained bubble-gumshoe into a fully-decked dick in a fedora and vintage John Garfield suit (mismatched with a sequined Liberace tie, a souvenir Doc picks up on his trip). Later, maritime lawyer and paranoid TV junkie Sauncho Smilax provides inadvertent commentary on the transition when he freaks out over the shift from black and white to color in The Wizard of Oz—“[I]f that’s what we see, what’s happening with Dorothy? What’s her ‘normal’ Kansas color changing into?” Pynchon’s dialogue has always been arch, pop-culture damaged, and/or downright goofy, so he expertly splices hippie-speak, surfer-tude, and hardboiled banter. He’s at his best when he keeps Inherent Vice talking.

Pynchon may be camera shy, even reclusive, but his novels are lively and every bit as strange and polyvocal as the world outside his head. Munching personal-sized pizzas with a fellow traveler in Pynchonia at a Greenwich Village restaurant, I recently compared notes on narrative structure and tone in various Pynchon novels. Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) has a long, arching shape to the narrative that reflects the novel’s preoccupation with parabolic rocket trajectories; it’s a further development of the yo-yoing eternal pursuit of Pynchon’s first novel, V. (1963). Similarly, the structure of Mason & Dixon (1997) matches its subject matter (the problematic establishment of the Mason-Dixon Line), and lays down a messy horizontal time line. Against the Day (2006), framed by a hot-air-balloon adventure tale, has an omni-directional, inter-dimensional narrative vectoring toward lateral realities. Vineland (1990), which some have found to be the most un-Pynchonlike of the lot (fringe theories suggest it was ghost written), reads like a series of comi-tragic digressions. Inherent Vice nods to many Pynchonian tropes, and the shiftiness of the plot relies on elements of strategies past, particularly those of The Crying of Lot 49 and Vineland. This time around, Pynchon’s narrative frame is a look back at something peering forward out of the haze, an intoxicating cloud of unknowing.

Much has been made of Inherent Vice’s ostensibly dumbed-down reefer madness (“Pynchon Lights Up,” announces Salon), but the real clouds come from the banks of time, and even if we haven’t taken a hit from one of Doc’s countless joints, we can agree: man, it’s complicated. The pro-and-analepsis get so thick that at times I wonder whether Pynchon himself is lost in the haze, but he hangs on to reasonable doubt with his roach-clip narrative. It’s tempting to read along with the Thomas Pynchon Wiki to cross-reference the appearances and disappearances of character and plot point, but fuck it: The haze is forgiving. Rooting through Inherent Vice’s earlier pages for the origins of later references has its pleasures; the flashbacks are enjoyable and inject an additional dose of non-linearity into the already spliced narrative, so any annoyance burns off quickly. At any rate, the back-and-forth reading provides analog kicks appropriate to the old wave we’re riding.

True to form, Pynchon introduces an extended cast of characters with an array of oddball monikers. Along our journey, we meet flat-landed femme fatal Shasta Fay Hepworth, semi-hidden sax man Coy Harlingen, kitchen psychotic Downstairs Eddie, Smile Maintenance specialist Dr. Rudy Blatnoyd, D.D.S., part-time cyborg acid-casualty runaway heiress Japonica Fenway, frozen-banana chomping hippie hater and self-described “Renaissance cop” Bigfoot Bjornsen, swastika-stamped, Aryan Brotherhood wannabe toady Puck Beaverton, Federal Agents Flatweed and Borderline, Sortilège, a vibe-sensitive guide and true believer in the lost, sunken Pacific island of Lemuria, and oboy, the list goes on! Not only are they cleverly named, but also iterated: Pynchon tells us everyone pronounces perma-stoned joker Denis’s name so it rhymes with “penis,” which gets us talking to ourselves while we read.

As usual with Pynchon, the plot is not the point, just a setup up for the writing and the sentiment, but here’s fair warning: spoilers loom on the horizon. Sailing in and out of the haze is the mysterious ship Golden Fang. Forget what it’s carrying—what is it? And what was that again? And so forth, as Pynchon is fond of typing into Doc’s mouth. There’s a love interest or three, and of course we’ll end up in Las Vegas, and, oh yeah, we’ll roll a few numbers, drive around happily captive to the Vibrasonic stereo… Hey, where are we going, exactly? Well, it seems we’re headed for the heart of darkness that lies in the dream of suburban planning. The plot, such as it is, is driven by a search for soul-challenged real estate developer Mickey Wolfmann after he sails off (perhaps) on the Golden Fang. And/or he might be heavily involved with a drug cartel by the same name, and he might also be involved in covert operations to use his latest radical gentrification project as training grounds for Blackwater-esque urban assault squads. On another hand, maybe he’s been committed to a high-class asylum by his wife and her lover. It’s, um, hazy.

We know Wolfmann is protected by a posse of Aryan Brothers who vaporize one day when Wolfmann himself steps into the haze at the temporary massage parlor outpost that services the workers at his latest environmentally unconscious housing development. Says Boris, a hunk of white meat for hire, “One minute you’re gettin a nice blowjob, the next it’s like fuckin Vietnam, assault teams everyplace you look, scuba units climbin out of the Jacuzzi, chicks runnin around screaming….” The haze, natch, intermingles with the fog of war. Here Pynchon heads for the PTSD lit section, where he rolls with Stephen Wright (Meditations in Green), Denis Johnson (Tree of Smoke), and James Crumley (Mexican Tree Duck). What happens to the killing machines that come back from battles abroad, not to mention the hard cases who re-emerge from the Joint in our incarceration nation? What sort of civilian complex will they inhabit and help build? And here’s where Inherent Vice threatens to engage with current events. After all, we’re building our own army of souls forged in the tank and the battlefield, for whom civilian life has become foreign. To whom are any of us loyal?

As Doc pursues some assemblage of truth, some dream of liberation from the agents of command and control, he realizes that he is not necessarily an agent of light cast in shadow. Indeed, he throws his own shade. Like us all, he is implicated in every plot he observes, and he sells himself along with his services. The haze pervades.

Related Articles from The Fanzine:

Michael Miller on Stephen Elliott’s The Adderall Diaries