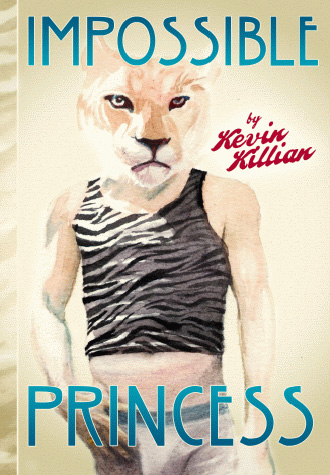

Impossible Princess by Kevin Killian

28.12.09

Having corresponded with Kevin Killian through a number of emails before reading Impossible Princess, his latest collection of stories, I was struck by how much of his personality is captured in his writing. When I read Impossible Princess it was almost as though it were written directly to me. This feeling of familiarity, however, was soon stopped abruptly by the appearance of an overwhelming darkness and longing that pervades these stories. And that’s the trick. Each of these stories (excluding “Young Hank Williams,” which serves as an introductory piece) sets a trap, a trap that entices the unsuspecting reader with a sheen of exquisitely written erotica and humor. The sex is reminiscent of what sex must have been like in 70s San Francisco before the AIDS plague struck and yet the reader, familiar with the modern dangers of sex, is confronted with his or her own reservations regarding the taboos of uninhibited promiscuity. As soon as one begins to get comfortable, Killian plunges them into something deeper, his real purpose. This isn’t just about getting your rocks off or being entertained for a moment or two. Those kind of stories would fade away almost immediately after turning the page. The stories in Impossible Princess stick.

Having corresponded with Kevin Killian through a number of emails before reading Impossible Princess, his latest collection of stories, I was struck by how much of his personality is captured in his writing. When I read Impossible Princess it was almost as though it were written directly to me. This feeling of familiarity, however, was soon stopped abruptly by the appearance of an overwhelming darkness and longing that pervades these stories. And that’s the trick. Each of these stories (excluding “Young Hank Williams,” which serves as an introductory piece) sets a trap, a trap that entices the unsuspecting reader with a sheen of exquisitely written erotica and humor. The sex is reminiscent of what sex must have been like in 70s San Francisco before the AIDS plague struck and yet the reader, familiar with the modern dangers of sex, is confronted with his or her own reservations regarding the taboos of uninhibited promiscuity. As soon as one begins to get comfortable, Killian plunges them into something deeper, his real purpose. This isn’t just about getting your rocks off or being entertained for a moment or two. Those kind of stories would fade away almost immediately after turning the page. The stories in Impossible Princess stick.

Every tale here emits a sensation of nostalgia or loss: in particular, nostalgia for lost love. And, yet, Impossible Princess is never depressing. It has the feel of Kevin Killian sitting next to you and telling you stories from his past. This feeling is deepened ever further by the fact that, in several stories, “Kevin” himself is the narrator. But the tricky thing for any reader confronted with a fictional text that reads like a confession is deciding whether or not you can believe the author. Is this really Kevin talking? Perhaps I don’t know him well enough. Doubtless, there is very little autobiography to be found in stories such as “White Rose”. But even when the autobiography element is absent, the author’s personality continues to pervade the story.

“White Rose”, for instance, can be read as a charming reexamination of Flannery O’Connor’s story, “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” Instead of beguiling a family to their death on a country road, here a could-be O’Connor villain (a la The Misfit) meets the narrator in a waiting room and takes him to an isolated location for a bout of rather rough sex (which is also reminiscent of Samuel Delany’s Hogg). By the time the reader has reached this story, they are comfortable with Killian’s combination of charm and dark humor. And, for some reason this reader isn’t at all surprised to find that Killian is a fan of O’Connor. Perhaps this is the reason that he, like she, is capable of skillfully combining dark undertones with an almost surreal sense of humor. In fact, I would go as far as to say that “White Rose” is the epitome of this text (although it was republished from Killian’s earlier, now out of print collection, I Cry Like A Baby) because it shows Killian’s literary roots, his ancestors. The more I think about it, the more Killian’s work reminds me of O’Connor’s collection A Good Man is Hard to Find.

Now for the salacious part. Are these stories sexy? Absolutely. But the sex scenes (and there is one in almost every story), while erotic, read like deliberate parodies of gay pornography. This is not a flaw. These sex scenes are often a huge part of the humor (read “Ricky’s Romance” to see my point) and are more meaningful than your average Best Gay Erotica sex scene. Take the bondage scene in “Spurt,” for example. The poor guy begging to be tied to the shower curtain rod and cut (carefully, mind you) gets exactly what he wants and more. Not to mention that Kevin ties him up using a rope a friend of his used previously to hang himself. However, the sex described in “Hot Lights” is potent in an entirely different way. Killian uses images of stretched assholes and cum-stained cocks to evoke a feeling of the almost Sadeian mechanics of the porn industry. Killian has immense talent when it comes to writing a sex scene beyond being merely “erotic”.

Three of the ten stories in Impossible Princess are collaborations and five of the stories have appeared in previous collections by Killian. The collaborations are proof of the strength of Killian’s voice; even though his voice is mingling with a coauthor’s, it never loses its own force and style. One almost feels as though you could pick these stories apart and discover which sections are written by Killian and which are written by the coauthor. And the fact that five of these stories have appeared elsewhere is irrelevant; all the stories fuse together to create one large, integrated piece––i.e., there aren’t any stories that don’t ‘fit.’ Readers familiar with Killian’s earlier work, no matter how familiar they believe themselves to be, are entering foreign terrain. It’s much darker here in the framing, but just as fantastic. Familiar or not, it’s a place worth seeing.

“Dietmar Lutz Mon Amour,” a new story, can be found right at the book’s center. The story ranges from the humorous to the, once again, longing aspects of a relationship between Killian and a painter, Dietmar Lutz, from Germany. Dietmar insists upon visiting Anton LaVey’s notorious “black house” and, when he and Kevin arrive to find it boarded up, they write notes to LaVey on paper airplanes and fly them into the windows. This is a very evocative scene that portrays, in its own unique way, the theme that the entirety of Impossible Princess manages to capture. And, in relation to the memoir aspect of the collection, I was not so surprised to find that one of Dietmar’s paintings mentioned is, in fact, real and hanging in the exact place Killian describes.

It might be corniness on my part, but I felt honored as a reader to be given these details of Killian’s life. And yet, whereas it’s nice to know that these nostalgic stories contain elements of truth, Killian also gives you stories like “Spurt” and “Hot Lights,” stories where the nostalgic memories are tainted by darkness and feelings of disillusionment. Killian is being honest. And that’s what a reader should expect. I was told by a friend that I should be sure to find something “wrong” with the collection in order to prevent the review from sounding like a blurb. Well, I can’t do that any easier than I would be able to find a flaw with Kevin himself. These are deeply personal stories and I think they are yet another testament to Kevin’s greatness and openness as both a writer and as a person.

––––––

Buy Impossible Princess here at the source. You can also read Killian’s work on Fanzine. We are still working on a collection of his film writings to be published by Fanzine Press in 2010, btw. After you buy and read Impossible Princess you can look forward to that, amongst the god knows what all else he has in the pot. It certainly is cooking.