James Baldwin, Uncollected

21.09.10

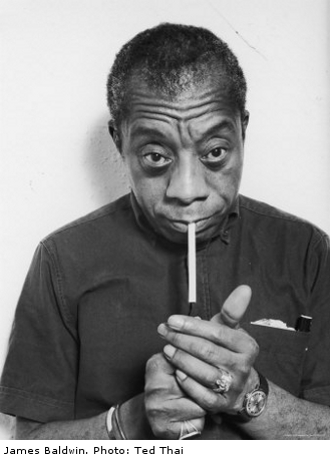

When I tell people how much I have always loved James Baldwin’s writing, they often respond by telling me, by gushing to me, really, about how much they love him, too. So often does this happen that I’ve come to believe that for many, proclaiming love for Baldwin’s writing is also proclaiming a love for Baldwin, the person, and, by extension, one or more of the diverse constituencies he’s so frequently taken to represent—a black writer, a gay writer, a civil rights activist, a writer whose language is infused with the sermonic cadences of the black church, a transatlantic traveler and ambivalent Parisian flâneur, a friend to celebrities from Nina Simone to Marlon Brando, and, for a good while there, a celebrity of significant proportions himself. The list goes on and on.

When I tell people how much I have always loved James Baldwin’s writing, they often respond by telling me, by gushing to me, really, about how much they love him, too. So often does this happen that I’ve come to believe that for many, proclaiming love for Baldwin’s writing is also proclaiming a love for Baldwin, the person, and, by extension, one or more of the diverse constituencies he’s so frequently taken to represent—a black writer, a gay writer, a civil rights activist, a writer whose language is infused with the sermonic cadences of the black church, a transatlantic traveler and ambivalent Parisian flâneur, a friend to celebrities from Nina Simone to Marlon Brando, and, for a good while there, a celebrity of significant proportions himself. The list goes on and on.

One of the other things people often say to me, even those who’ve already made clear their love for Baldwin, is how much they prefer his essays to his novels, an opinion shared by any number of Baldwin critics, scholars, and biographers. Baldwin’s best writing came, the common wisdom goes, in the intensely introspective essays in which he often drew upon his experiences growing up black and poor in Harlem, and then, later, as a black American living abroad in France, in order to illuminate larger, and urgent, questions about the injustices of race in America.

A new Baldwin book out this month from Pantheon, The Cross of Redemption: The Uncollected Writings, will do little to overturn this widespread view of Baldwin as a master of the essay form––which, of course, he was, from his finely wrought early essays like the controversial “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” in which he took down his literary mentor, Richard Wright, to his signature melding of the personal and the political in “Notes of a Native Son.” Still, as a reader who longs to understand Baldwin better, both as a writer and as a man, I’m profoundly disappointed in this collection. Here’s why.

* * *

For me, in the beginning, it was Baldwin’s fiction that enthralled the most. Perhaps because that’s what I most wanted to write myself. I grew up in the ’80s in Washington, D.C., the only son of a civil rights lawyer and one of the few white students in the city’s embattled public schools. Unsure about my sexuality, I was drawn to the way Baldwin tackled the intertwined issues of race and sex in his fiercely and inimitably irreverent style, giving flesh and blood life to his characters on the page in a way I’d never seen before. In a way, in fact, I previously couldn’t have imagined possible.

At stake for me was more than a literary apprenticeship. Like many other gay men of my generation––which is to say, those of us born before the increased visibility of gays and lesbians in television, film, and other forms of popular culture––I needed to hear from writers (who were, in the end, strangers, really) that growing up gay under the shadow of AIDS might not mean the only future available to me was some grisly version of the early and excruciatingly painful death the whole world seemed to be saying was awaiting every last one of those kinds of men, who, in my mind back then, at least, were hardly men at all. The fact that Baldwin never wrote a single word about AIDS was one of the main reasons why he appealed to me so much, although, as I’d later learn, he did lose one of his last lovers to the epidemic, his ashes scattered in the garden of Baldwin’s farmhouse in Saint Paul-de-Vence, in the south of France, where Baldwin himself died, of cancer, in 1987. Reading his fiction allowed me to indulge in a fantasy of a time, and a gay life, before the onset of the AIDS epidemic, just recent enough to look familiar to me, but also unencumbered by the weight of death and disease present in so much of the gay fiction that was being published as I came into an awareness of my own, as they say, “sexuality.”

At stake for me was more than a literary apprenticeship. Like many other gay men of my generation––which is to say, those of us born before the increased visibility of gays and lesbians in television, film, and other forms of popular culture––I needed to hear from writers (who were, in the end, strangers, really) that growing up gay under the shadow of AIDS might not mean the only future available to me was some grisly version of the early and excruciatingly painful death the whole world seemed to be saying was awaiting every last one of those kinds of men, who, in my mind back then, at least, were hardly men at all. The fact that Baldwin never wrote a single word about AIDS was one of the main reasons why he appealed to me so much, although, as I’d later learn, he did lose one of his last lovers to the epidemic, his ashes scattered in the garden of Baldwin’s farmhouse in Saint Paul-de-Vence, in the south of France, where Baldwin himself died, of cancer, in 1987. Reading his fiction allowed me to indulge in a fantasy of a time, and a gay life, before the onset of the AIDS epidemic, just recent enough to look familiar to me, but also unencumbered by the weight of death and disease present in so much of the gay fiction that was being published as I came into an awareness of my own, as they say, “sexuality.”

Baldwin’s writing spoke to me so powerfully early on because my knowledge of his homosexuality brushed up against my growing understanding of his close affiliation with the civil rights struggle in the popular consciousness, a movement that had been formative for my father, who’d attended the March on Washington as a young, idealistic law school graduate and anti-war activist in D.C. It was Baldwin’s blackness, I felt, that gave me the permission to love him, and to say so out loud in front of other people, including, eventually, my family. By saying I loved James Baldwin, I was clearly trying to align myself with my father and his political commitments. But I was also struggling to find a way to love myself, not in spite of my desire for other men, but because of it, without having to fully admit to myself (or to anyone else, for that matter) that this was what I was trying, and failing miserably, to do.

The first book I read by Baldwin was his 1952 novel, Giovanni’s Room, which describes a tragic love affair between two men, a white American and an Italian, in Paris. I was fifteen years old when I borrowed my twin sister’s copy of the novel, without telling her, after hearing someone at school describe Baldwin as a faggot. I can vividly remember taking the book into my bedroom, how I locked the door behind myself, out of fear that someone in my family would see it in my possession, and think I was a faggot, too. I pored through its pages, reading it cover to cover in one sitting, before finally hiding the book beneath my mattress when I was finished, as if it were pornography.

There was one passage in particular that I returned to so many times in the weeks and months that followed that after a while whenever I opened the book, it would turn right to this page, automatically, almost as if an unseen hand were guiding me. The narrator, David, is describing his first sexual encounter with another boy back in the States. “Joey’s body was brown, was sweaty, was the most beautiful creation I had ever seen,” Baldwin writes,

There was one passage in particular that I returned to so many times in the weeks and months that followed that after a while whenever I opened the book, it would turn right to this page, automatically, almost as if an unseen hand were guiding me. The narrator, David, is describing his first sexual encounter with another boy back in the States. “Joey’s body was brown, was sweaty, was the most beautiful creation I had ever seen,” Baldwin writes,

But Joey is a boy. The power and the promise and the mystery of

that body made me suddenly afraid. That body suddenly seemed to

be the black opening of a cavern in which I would be tortured til

madness came, in which I would lose my manhood…I could have

cried, cried for shame and terror, cried for not understanding how

this could have happened to me, how this could have happened in me.

An overwhelming sense of terror and relief washed over me when I read these words for the first time. Terror, because Baldwin seemed to be describing, and with such stark precision, the deep shame I felt about my own burgeoning desire for the bodies of the other boys at school, who more often than not were black. But relief, also, because it was proof that homosexuality could be found in something that I loved: books. All at once, it seemed, I began to realize that the word “gay” might mean something other than a diseased future, a living death, really, or something the boys at school called each other, and called me, as well, whenever they wanted to pull forth something particularly nasty from their catalogue of insults. Instead, it was something a famous writer, a black writer, a writer valued by my teachers at school, took seriously enough to write about, and to describe as beautiful, of all things.

All of which is to say that for me, from the very beginning, falling in love with Baldwin’s writing was like falling into a deep well of ambivalence and loss, with no one, and nothing, to help me climb my way out. By the time I graduated from high school, I’d read two more of his novels, the first of which, Go Tell It On the Mountain, I actually read in one of my English classes. And though nobody mentioned homosexuality in our class discussions, the relationship between the protagonist, John, and an older boy, Elisha, struck me immediately as a homoerotic one, thanks to passages like this one:

He had sinned. In spite of the saints, his mother and his father,

the warnings he had heard from his earliest beginnings, he had

sinned with his hands a sin that was hard to forgive. In the school

lavatory, alone, thinking of the boys, older, bigger, braver, who

made bets with each other as to whose urine could arch higher, he

had watched in himself a transformation for which he would never

dare to speak.

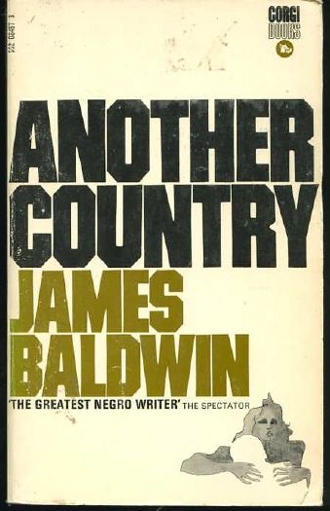

Actually, to be honest, the term, “homoerotic,” is probably not the one I would have used to describe the experience of reading this passage back then. It’s too definitive, too analytical, and too comfortable in its own knowledge, its own skin. Instead, I felt it as a kind of electricity running up my spine. Next, on my own, I read Baldwin’s best-selling 1962 novel, Another Country, which returned me to the terrain of the terrifying in the form of the abusive relationship depicted between Rufus Scott, a black trumpet player, and his Southern white girlfriend, Leona. But it also provided an image of the possibility of blissful love between men in Paris, in the form of the characters of Yves and Eric, and I remember, as I entered their world in Baldwin’s pages, I began to think that maybe, just maybe, being gay wouldn’t be quite so bad after all.

It wasn’t until I got to college that I finally read those majestic essays of his. And they were a revelation for me, from “Equal in Paris” to “No Name in the Street.” Even though I was white, or perhaps because I was white, I immediately understood and identified with Baldwin’s closing point in “Stranger in the Village,” his reflection on his experience as the only black person in the small Swiss Village where he completed his first novel: “This world is white no longer, and it will never be white again.” In junior high school, as the only white boy on the basketball team, my teammates had given me the nickname “Politics” because they felt, and rightly so, that the coach had only put me on the team because he wanted to have at least one non-black player on the squad. Reading Baldwin’s essays gave Politics a way to think about politics. They gave me a language for thinking about not just blackness, but my own whiteness, in a self-conscious, self-critical way. And in doing so, made it impossible for me to ignore the inextricable relationship between the personal and the political, and how the vast majority of white Americans had never looked deeply into themselves in order to question their sense of racial belonging, their privileges, and their complicity, sometimes unconscious, sometimes not, with racist institutions and practices.

It wasn’t until I got to college that I finally read those majestic essays of his. And they were a revelation for me, from “Equal in Paris” to “No Name in the Street.” Even though I was white, or perhaps because I was white, I immediately understood and identified with Baldwin’s closing point in “Stranger in the Village,” his reflection on his experience as the only black person in the small Swiss Village where he completed his first novel: “This world is white no longer, and it will never be white again.” In junior high school, as the only white boy on the basketball team, my teammates had given me the nickname “Politics” because they felt, and rightly so, that the coach had only put me on the team because he wanted to have at least one non-black player on the squad. Reading Baldwin’s essays gave Politics a way to think about politics. They gave me a language for thinking about not just blackness, but my own whiteness, in a self-conscious, self-critical way. And in doing so, made it impossible for me to ignore the inextricable relationship between the personal and the political, and how the vast majority of white Americans had never looked deeply into themselves in order to question their sense of racial belonging, their privileges, and their complicity, sometimes unconscious, sometimes not, with racist institutions and practices.

But his essays did more than that, because part of Baldwin’s brilliance is that he rarely wrote about racism as an isolated form of oppression. Instead, in essays like “The Male Prison,” “The Preservation of Innocence,” and “Here Be Dragons,” he forced readers to confront the connections between race, masculinity and sexuality. I devoured these essays, in particular, because they were the few places where he offered glimpses into his thinking about homosexuality, about how, in America, in his own words, “there is a panic which is close to madness” when it comes to “the ever present danger of sexual activity among men.”

As I tried to summon the courage to overcome my own panic and come out of the closet, I scoured Baldwin’s essays for any revelations about how he’d managed to come to terms with his sexual desire for other men. But except for the occasional vague paragraph or cryptic aside, there weren’t any. So I turned to his biographies. One of them barely mentioned his homosexuality at all. Another acknowledged it but hardly as something central to the person he was. Only David Leeming’s biography took the time to integrate these experiences into the narrative of his life, but in doing so he was forced to cloak the names of most of Baldwin’s male lovers in pseudonyms. And so I became adept at reading between the lines, seeking meaning in the gaps, the hesitations, the footnotes.

The more I learned, and didn’t learn, about Baldwin’s personal life, the more I came to understand that he was certainly no poster boy for the affirmation of gay identity. In fact, he disavowed the term “gay,” both as a way to describe himself, and, especially, his lovers, who were frequently involved with or married to women and, in any event, lived predominantly heterosexual lives. In an interview that took place just a few years before he died, for example, one of the rare moments when he agreed to speak publicly about the subject at all, Baldwin told the Village Voice that he saw homosexuality as a “verb,” not a “noun,” and went on to explain that “the word ‘gay’ has always rubbed me the wrong the way,” adding, tellingly, that “the people who were my lovers were never, well, the word gay wouldn’t have meant anything to them.”

As I read more about Baldwin’s life, and discovered queer theory, I came to believe that he was providing a useful critique of the way rigid categories of identity, such as gay, can be used to further police the socially marginalized. I also understood how coming out into a largely white (and racist) gay world must have been an unappealing proposition for him. And yet I continued to want to know. But to know what, exactly? Whether he was really “gay,” despite his protestations to the contrary? But everybody knew that he only really slept with men, so there wasn’t much to be discovered there. So what kind of personal information did I really want to know?

As I read more about Baldwin’s life, and discovered queer theory, I came to believe that he was providing a useful critique of the way rigid categories of identity, such as gay, can be used to further police the socially marginalized. I also understood how coming out into a largely white (and racist) gay world must have been an unappealing proposition for him. And yet I continued to want to know. But to know what, exactly? Whether he was really “gay,” despite his protestations to the contrary? But everybody knew that he only really slept with men, so there wasn’t much to be discovered there. So what kind of personal information did I really want to know?

When I came upon one of Baldwin’s biographers, James Campbell, briefly noting the “salacious stories” that swirled around his love life, and how many of them were set in motion by the fact that many of his lovers were younger than he was, I was stopped in my tracks:

While Baldwin himself would have attributed the urge to pass on

dirty stories about others as the conscious mind’s defense against

its own unconscious and forbidden longing, the gossip nonetheless

persists. Jimmy only liked fair young boys, reports one of Baldwin’s

friends; Jimmy only liked truck-driver types, says another, the bigger

the better. Jimmy only liked white, Jimmy only liked black…

Reading these words now, I’m struck by the irony of the fact that part of the genius of Baldwin’s writing is precisely his willingness, in his fiction, at least, to explore the complexities of “forbidden longing.” But back then, what I secretly wondered was this: in another world, if Baldwin were still alive, would he like, and maybe he even love me? Would I be able to love him back? Would I ever be able to love myself?

* * *

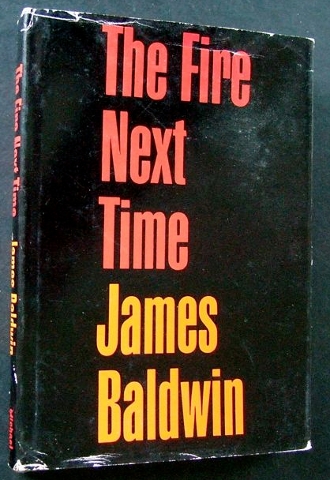

Love, after all, self-love and love for others, is one of Baldwin’s greatest themes, and quite possibly his most abiding concern of all. “If love will not swing open the gates, no other will or power can,” he wrote in one of his most important essays on race relations in the United States, “The Fire Next Time,” published just as Malcolm X was beginning to pose a serious challenge to the popular, non-violent ethos of Martin Luther King. Baldwin’s critics have sometimes called his belief in the redemptive powers of love sentimental, a fact he acknowledged himself with a self-deprecating sense of humor in Another Country when one of its bohemian characters says to another: “That love jive, sweetheart. Love, love, love!” But I think Baldwin’s conception of love is more layered, and edgier, than he is sometimes given credit for. Because in that novel, and elsewhere, including many of his best essays and short stories, Baldwin bravely explored the psychosexual elements of racism by consistently imagining the struggle for understanding between black and white Americans as a struggle between lovers; or, as he wrote, again, in his essay “The Fire Next Time”: “If we—and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others—do not falter in our duty now, we may be able, handful that we are, to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world.”

Many critics have argued, for example, that Baldwin intended the fraught relationship between Rufus and Leona in Another Country to stand as an allegory for the interracial violence, physical and psychological, internalized and externalized, at the heart of the nation’s long history of racial injustice. Others, meanwhile, have also suggested that sexual love between men in the novel––Yves and Eric, in particular, and for one night, Eric and Vivaldo––symbolizes the loosening of the social and sexual mores that underpin this society, and the breaking away towards the possibility of something revolutionary and new. Not that Baldwin imagined that this breaking away was going to be easy. On the contrary, as he wrote, once again, in “The Fire Next Time”: “What I am asking is impossible. But in our time, as in every time, the impossible is the least one can demand.”

Many critics have argued, for example, that Baldwin intended the fraught relationship between Rufus and Leona in Another Country to stand as an allegory for the interracial violence, physical and psychological, internalized and externalized, at the heart of the nation’s long history of racial injustice. Others, meanwhile, have also suggested that sexual love between men in the novel––Yves and Eric, in particular, and for one night, Eric and Vivaldo––symbolizes the loosening of the social and sexual mores that underpin this society, and the breaking away towards the possibility of something revolutionary and new. Not that Baldwin imagined that this breaking away was going to be easy. On the contrary, as he wrote, once again, in “The Fire Next Time”: “What I am asking is impossible. But in our time, as in every time, the impossible is the least one can demand.”

What Baldwin was asking for was for blacks and whites to find a way to love each other.

If the impossibility of this love, and its enduring necessity, was one of Baldwin’s most recurring themes in his public life as a writer, it was also the arena of some of his most profound personal disappointments. Not so much in the sphere of platonic love between the races, because this he found in his many friendships with white men and white women, including his high school teacher, Mary Painter, his high school classmate and eventual collaborator, the photographer Richard Avedon, and, later, famous writers such as William Styron, and even, in a more complicated way, to be sure, Norman Mailer. (Here I’m underscoring the reality that interracial friendship was central to Baldwin’s life world, but it’s important to acknowledge that many of Baldwin’s closest friendships were with other blacks, and that many of his most intense bonds were with members of his own family).

But in his romantic and sexual relationships, particularly during the first half of his life, Baldwin’s often-thwarted desire for a number of white men, in particular, was a source of great pain and frustration for him. (Again, as is so often the case when writing about a figure as complex as Baldwin, another qualifying parenthetical is required to note that with the important exception of the man Baldwin called his “first love,” Teddy Pelatowski, Baldwin’s desire for white men was most often for European, not American, white men, a fact that many Baldwin critics overlook. Later in his life, Baldwin would become involved with a number of men of color, from the United States and from West Africa).

The truth is Baldwin’s erotic life was never exactly angled towards happiness. As Hilton Als writes in a piece on Baldwin that appeared in The New Yorker a few years back, Baldwin “tended to be attracted to straight and bisexual men, who increased the sense of isolation he fed on. Even Lucien, his great love, was primarily attracted to women. For Baldwin, the first principle of love was love withheld; it was all he had ever known.” Here Als is referring to the impact Baldwin’s relationship with his stepfather, who abused him physically and emotionally throughout his childhood in Harlem, would have on his romantic entanglements with other men as an adult. “Lucien,” meanwhile, is Lucien Happersberger, the seventeen year old would-be artist Baldwin met and fell in love with when he moved to Paris in 1948 at the age of twenty-four. After publishing book reviews in a number of smaller publications in New York, including The Nation, Baldwin had come to Paris on a small literary fellowship he’d been awarded from the Rosenwald Foundation. Baldwin wanted to avoid the trap of becoming just a “Negro writer,” as he later wrote of his decision to leave America, but the truth is he also came to the City of Light in search of love, and he found it, for a time, and then sporadically throughout his life, with Lucien, to whom he eventually dedicated Giovanni’s Room.

As the poet Richard Howard told Als, part of Baldwin’s problem, and his solution, in his love affair with Lucien, and others, was that Baldwin was “this rather silly, giddy, predatory fellow who was extraordinarily unattractive looking. There’s a famous eighteenth century person who used to say, ‘I can talk my face away in twenty-five minutes.’ And Jimmy could do just that.” Whether this rather unflattering portrait is an accurate one or not, it’s certainly the case that over the course of his life Baldwin managed to keep Lucien, and then after him, a fairly voluminous string of lovers, some more significant to him than others, by his side for long stretches of time. He did so through a combination of the inestimable force of his personality, his fame, the genuine affection many of these men had for him, and his money, with which he was apparently quite generous when he had it. In the end, however, none of them were able to provide Baldwin with what he claimed, time and time again, he wanted most: an enduring, and stable, domestic and romantic partnership with another man. Even with all of his many accomplishments as a writer and an artist, and the sense so many around him had that he was truly a wonderful friend, brother, and son, this was one of the great dreams that constantly eluded him.

As the poet Richard Howard told Als, part of Baldwin’s problem, and his solution, in his love affair with Lucien, and others, was that Baldwin was “this rather silly, giddy, predatory fellow who was extraordinarily unattractive looking. There’s a famous eighteenth century person who used to say, ‘I can talk my face away in twenty-five minutes.’ And Jimmy could do just that.” Whether this rather unflattering portrait is an accurate one or not, it’s certainly the case that over the course of his life Baldwin managed to keep Lucien, and then after him, a fairly voluminous string of lovers, some more significant to him than others, by his side for long stretches of time. He did so through a combination of the inestimable force of his personality, his fame, the genuine affection many of these men had for him, and his money, with which he was apparently quite generous when he had it. In the end, however, none of them were able to provide Baldwin with what he claimed, time and time again, he wanted most: an enduring, and stable, domestic and romantic partnership with another man. Even with all of his many accomplishments as a writer and an artist, and the sense so many around him had that he was truly a wonderful friend, brother, and son, this was one of the great dreams that constantly eluded him.

How curious, then, that with the important exception of David Leeming’s biography, chroniclers of Baldwin’s life have long overlooked the significance of the fact that the writing of arguably every single one of his books was influenced by his sexually-charged relationships with male mentors, lovers, friends, and protégés, and not only Lucien. (I’m thinking here, for starters, of Baldwin’s mentor, the black gay painter, Beauford Delaney, who fell in love with a teenaged Baldwin when they first met, and to whom Baldwin dedicated several literary works; and the enigmatic French artist, Yoran Cazac, Baldwin’s collaborator, to whom he dedicated his 1973 novel, If Beale Street Could Talk).

Which is to say, what’s been erased is that for Baldwin, the creative act was always an erotic one, a gap in knowledge that has been an enormous impoverishment for Baldwin scholars, biographers, and readers alike. Even James Campbell, who asserts in his Baldwin biography that “the same two obsessions dominated Baldwin through every period, in every place: his love life and his writing life,” is only able to provide glimpses of the first of these obsessions, and almost no discussion of the relation between the two. Instead, what we are left with is literature, and literary history, without key aspects of the author’s biography, a life stripped of the same-sex intimacy that inspired some of Baldwin’s most magnificent, and, in some cases perplexing, creations, a violation from beyond the grave of his own claim that “all art is a confession, more or less oblique. All artists, if they are to survive, are forced, at last, to tell the whole story; to vomit the anguish up.”

* * *

For some time now, I’ve been aware of the existence of an unpublished trove of Baldwin’s personal letters whose contents might begin to fill this gap in our understanding of his life and work. These letters are likely replete with all the anguish, and all the triumphs, that make Baldwin not just a famous writer but also a human being, like the rest of us. (Baldwin, who battled depression throughout his life, tried to commit suicide more than once. That he didn’t succeed is one of these triumphs). But in the pages of the New Yorker, Hilton Als laments that the Baldwin Estate has suppressed these letters (which he calls the “one great Baldwin masterpiece waiting to be published”) because his family “felt he shed a negative light on them, particularly David Baldwin, who was their father and not his; and they were uncomfortable with his homosexuality.”

When I saw the words “uncollected writings” and “redemption” in the title of the new Baldwin book, I thought for a moment that perhaps the Baldwin Estate had finally reversed its decision, my hopes bolstered by the fact that the black gay novelist, Randall Kenan, edits the volume (and whose textured introduction acknowledges that Baldwin was gay, the “ultimate outsider,” as he calls him). But I was wrong. The book offers no new writing from Baldwin, epistolary or otherwise. Instead, it brings together Baldwin’s previously published essays, reviews, and open letters that didn’t make the cut for his career-defining tome, The Price of the Ticket: Collected Non-Fiction, 1948-1985, which sits before me on my desk now, its coffee-stained pages highlighted in multiple colors, notes scrawled in the margins, all these markings remnants from my college days.

That’s not to say that this new volume isn’t a valuable one. There are some great pieces here, to be sure. Some of them I’d read before, including his excellent essays, “The Uses of the Blues,” “On Being White…and Other Lies,” and “Why I

Stopped Hating Shakespeare.” Many others I hadn’t read, most notably his fantastic profile, “The Fight: Patterson vs. Liston,” which is worth the price of the book on its own. Also included is a speech Baldwin made as part of the Liberation Committee for Africa in 1961, one that takes on a renewed resonance now in the Obama era:

Bobby Kennedy recently made me the soul-stirring promise that one

day—thirty years if I’m lucky—I can be President too. It never entered

this boy’s mind, I suppose—it has not entered the country’s mind yet—

that perhaps I wouldn’t want to be. And in any case, what really exercises

my mind is not this hypothetical day on which some other Negro “first”

will become the first Negro President. What I am really curious about is

just what kind of country he’ll be President of.

Moments like this one remind us that Baldwin was, after all, as so many described him, a prophet. But more than anything, as I made my way through the volume, I felt as if I were back in college again, trying to read between the lines of Baldwin’s non-fiction for news about him that was also news about myself, and coming up short time and time again. (I might have found some if the volume had included selections from Baldwin’s letters to the poet, Harold Norse, a friend and romantic interest of Baldwin’s in his early Greenwich Village years when he was struggling to come to terms with his sexual and racial identity. As Norse writes in his memoirs: “Jimmy’s letters from Woodstock, where friends put him up so he could work on his novel in a peaceful atmosphere, were full of fears about his future, about poverty, obscurity, lack of love. ‘What’s going to become of me?’ he’d write in hopeless despair… Jimmy said that he felt estranged from Harlem, with its poverty and limitations and, except in the Village, felt alien in the white world.”).

The absence of these kinds of letters are all the more glaring when one reads the volume’s inclusion of Baldwin’s 1968 ode to Stokely Carmichael, “Black Power,” a sad reminder of how badly he wanted to be accepted by a movement, and a younger generation of black male radicals, who rejected him precisely because of his sexual relationships with other men, and white men, in particular. (A strain of anti-Baldwin sentiment that reached its most vitriolic in Eldridge Cleaver’s 1968 tract, Soul on Ice, which condemned Baldwin’s homosexuality as a “racial death wish”). Indeed, Baldwin must have known that claiming a more public homosexual identity would have disqualified him from assuming a more prominent leadership role in the civil rights movement, but in the end this happened anyway, to a large extent, as rumor and innuendo earned him what is, let’s face it, the rather witty nickname, Martin Luther Queen.

The absence of these kinds of letters are all the more glaring when one reads the volume’s inclusion of Baldwin’s 1968 ode to Stokely Carmichael, “Black Power,” a sad reminder of how badly he wanted to be accepted by a movement, and a younger generation of black male radicals, who rejected him precisely because of his sexual relationships with other men, and white men, in particular. (A strain of anti-Baldwin sentiment that reached its most vitriolic in Eldridge Cleaver’s 1968 tract, Soul on Ice, which condemned Baldwin’s homosexuality as a “racial death wish”). Indeed, Baldwin must have known that claiming a more public homosexual identity would have disqualified him from assuming a more prominent leadership role in the civil rights movement, but in the end this happened anyway, to a large extent, as rumor and innuendo earned him what is, let’s face it, the rather witty nickname, Martin Luther Queen.

If there is any redemption to be found in The Cross of Redemption it’s in those places where the volume can’t help but hint at the unpublished, personal letters that aren’t there. In “A Word Directly from Writer to Reader,” Baldwin responds to an editor’s question about how writing in the ’50s made special demands on him as a writer: “But finally for me the difficulty is to remain in touch with the private life. The private life, his own and that of others, is the writer’s subject—his key and ours to his achievement.”

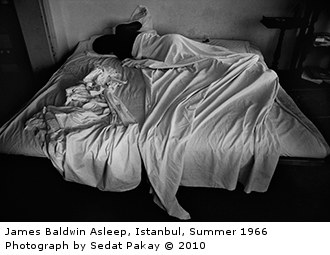

And in a wonderful series of open letters commissioned by and published in Harper’s in 1963, “Letters from a Journey,” Baldwin writes to his agent back in the States from Turkey, Israel, and elsewhere. Here he emerges not as a spokesperson for a movement, or a race, but as a living, breathing man, full of self- doubt, and in need of respite from all the pressures he faced back in the States: “I must say, it’s rather nice to be in a situation in which I haven’t got to count and juggle and sweat and be responsible for a million things that I’m absolutely unequipped to do.” But a couple letters later, just as it seems as if Baldwin is about to delve into some of the details of his personal life, he cuts himself off: “Well,” he writes, as if the whole world were watching. “More of this in a real letter.”

____________________

Related Articles from The Fanzine:

Louis Chude-Sokei on blackface, representing the other and Congolese writer Alain Mabanckou

Jeff T. Johnson on Thalia Field and Leslie Scalapino

Interview with Tony O’Neill, author of Sick City, in some of Los Angeles’ seediest bars