Talk Show 28 with Thomas Beller, Joshua Furst, Elizabeth Graver, Dave King, and Binnie Kirshenbaum

29.07.09

Thomas Beller’s short stories have appeared in The New Yorker, The Southwest Review, Ploughshares, Harper’s Bazaar, Mademoiselle, Best American Short Stories, and are forthcoming from Another Chicago Magazine, The Seattle Review and The St. Ann’s Review. He is the author of three books, Seduction Theory, The Sleep-Over Artist, and How To Be a Man, and editor of several anthologies, including Lost and Found: Stories From New York, forthcoming this spring. He is a founder and co-editor of Open City Magazine, and creator of the website www.mrbellersneighborhood.com. He teaches at Tulane University. Visit Tom at www.thomasbeller.com.

Joshua Furst is the author of two books, Short People, a collection of stories, and The Sabotage Café, a novel. He lives in New York City and teaches fiction and playwriting at The Pratt Institute. Visit Joshua at www.joshuafurst.com.

Elizabeth Graver is the author of three novels: Unravelling, The Honey Thief, and Awake, as well as a story collection, Have You Seen Me? Her work has been included in Best American Short Stories, Best American Essays, and Prize Stories: The O. Henry Awards. At work on a new novel, she teaches at Boston College. Visit Elizabeth at www.elizabethgraver.com.

Dave King is the author of the novel The Ha-Ha, named one of the best books of 2005 by The Washington Post, The Christian Science Monitor, and The Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, and a film version is in development by Warner Brothers Pictures. In addition, The Ha-Ha earned Dave King the 2006 John Guare Writers Fund Rome Prize Fellowship from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Dave’s poems and essays have appeared in The Paris Review, The Village Voice and Big City Lit, and in the Italian literary journal Nuovi Argomenti. He divides his time between Brooklyn and the Hudson Valley of New York and teaches at New York University’s Gallatin School of Interdisciplinary Studies. Visit Dave at www.davekingwriter.com.

Binnie Kirshenbaum is the author of five novels and a story collection. She is currently the chair of the M.F.A. program at Columbia University, and her new novel, The Scenic Route, will be published in May 2009 by Ecco/HarperCollins. Visit Binnie at www.binniekirshenbaum.com.

––Name a ribbon or certificate you won in grade school.

Beller: It was in Camp—Tennis VI. This was the highest rank of tennis accomplishment at the Cape Cod Sea Camps, which I attended.

Furst: First Place: Medley Relay – Arlington County, Virginia, YMCA Intramural Swim Meet 1976. An actual blue ribbon embossed in gold.

Graver: When I was in 2nd Grade, I wrote a story called “A Moment Too Late,” in which a girl and her sister go on a great ocean adventure and end up being swallowed by a whale. In the first version, fairies try to rescue the two girls but arrive “a moment too late.” This—“A Moment Too Late”—was the last line of the story, as well as the title. I remember enjoying the symmetry of that. My teacher wanted me to enter the story into a children’s writing contest sponsored by the local newspaper, but she strongly advised me to revise the ending and make it happy if I wanted to have a shot at winning. My story won 3rd place for the Grades 1-3 category.

King: In third grade I wrote a Halloween story that was judged the best in our class.

King: In third grade I wrote a Halloween story that was judged the best in our class.

Kirshenbaum: I thought for sure I must have won something in grade school; I was a good student and not the worst athlete, but if I did win a ribbon or certificate, I don’t remember it, which leads me to conclude that I didn’t win anything because surely I would’ve remembered if I had. The closest I came to an accolade, any recognition of achievement was in the fifth grade when I made the snowflakes for the Winter Pageant. On the program, at the bottom, on a line unto itself was printed: Snowflakes by Binnie Kirshenbaum.

––How did you win this accolade?

Beller: For each level, Tennis I, II, and so on, a counselor would put you through the paces on the court. You would have to hit a certain number of backhands, forehands, execute certain things. For the tennis six it was quite rigorous. I dimly recall there being a requirement for an "American Twist," serve. This involved throwing the ball above your head in such a way that you had to arch your back and give it a lot of topspin, coming over the ball. As you might gather from the name, Cape Cod Sea Camps was focused on sailing. I did not sail. The second most intense activity at the camp was tennis, and I was into tennis. However I was a dinker. I fought my way up the tennis ladder by being someone who would hit the ball back a lot and, at the key moment, dink it over the net so it hit the service line and just died. It is the least graceful form of tennis. I hated myself for playing that way, but then when the competition got intense I always went to this special skill, the dink. In some ways I feel like I have been a recovering dinker ever since. With this in mind I was not thought to be a big tennis talent and Tennis VI seemed beyond me. I had barely squeezed my way through the Tennis V test. I don’t recall who administered the test for Tennis VI. I think it was a woman. I do remember thinking she was being very easy on me. At the end she said I got it. I was amazed. And here is why this is important to me––I told my friends that night at assembly. It was a special assembly where the end of the year awards were given out. I told my friend Mike Kaneb in this really low key way that I passed Tennis VI, and in his fraught but understated way, he went nuts. He had a murmurous style, but he got quite animated, he thought it was the greatest thing, he couldn’t believe it, and neither could I. But I was already braced for the blow that was coming that night at the awards ceremony, where they handed out the prize for best this and best that. Among they prizes was best actor, or most accomplished in drama, or whatever the called it. There was a big musical at the end of camp – that year it was Oklahoma – and then throughout the season there were these funny little melodramas that were put on every week. You rehearsed like crazy all week and then put on the show on Sunday. I always did these weekly things, never did the big musical, and that year I had really been on fire in those weekly shows cracking everybody up. I still recall one of my lines, I was a cop, I looked around and said, "There’s something in the air!" For some reason people really laughed when I delivered that line. But the prize tended to go to whomever had been the lead in the musical. To this day I look back at that evening and my dread of what would happen and think it anticipates some of the weird tension between short story writers and novelists––weekly play versus end of year musical. So here comes the big moment and the winner is… The guy who was the lead in Oklahoma. As I knew it would be. And yet. So for me this great peak, Tennis VI, has always been redolent of the disappointment, oddly enough, that came later that night. I should add as an addendum that before changing it to the roman numerals, above, I wrote it out as words, Tennis One and so forth, and at the end there, I wrote Tennis Sex. Make of this what you will.

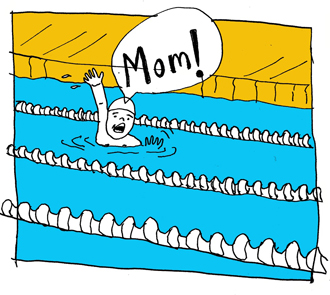

Furst: By five years old, I’d risen to the rank of Sea Horse in the swim classes I took at the Alexandria YMCA. This meant that I’d mastered the rudiments not only of the crawl but also of the breast- and backstrokes. I was no longer a Minnow. I had rank and expertise. Having shown such promise at such a young age, I joined the swim club. (Was it a club or a team? It must have been a club—I’d never have made the cut on a team).

In my one and only meet, I swam the breaststroke leg of the 50-yard relay. My partners in this race consisted of two tykes like me, and anchoring us on the butterfly, a toned and powerful Dolphin (a Dolphin being someone who’d risen as high as you could go in the YMCA’s system). It was an exciting day, charged with the smell of the chlorine and athlete’s foot. The fold-out risers were packed with parents, mine included. When my turn came, I dove off the blocks, swam halfway across the pool and stopped, treading water as I searched the stands for my mother. Finding her, I waved with furious pride—Mom! It’s me! Look! I’m swimming! Look! I’m racing! Look! Look! She waved back and the joy on her face in that moment drowned out the boos of my teammates.

Despite all this, we clobbered the competition.

Despite all this, we clobbered the competition.

Graver: I’ve always assumed it was because I changed the ending, but maybe the newspaper had an editor with a dark sensibility and I would have won first place if I’d stuck to my original draft. In the revised version, fairies swooped in a moment too late, as they had before, but then more fairies swooped in, a moment not too late. It was dumb. The title no longer worked, but I kept it anyway. I didn’t like the new version of the story, but I won a prize, and I liked that. Now I have a daughter in 3rd grade. One day she came home from school saying that all stories need to have a problem and a solution, and I found myself saying (shrilly) No, there doesn’t have to be a solution; in life, there’s not always a solution! Except in your life, I added pathetically. And your sister’s.

King: I cheated. My story had some sort of twist at the end, and though I made up my own characters and setting, I borrowed the twist from something I’d read. I think it’s possible that the whole class had read the story I plagiarized, for I can recall my feelings of shock and chagrin when the winning story was read aloud on Halloween day. I hadn’t bargained for that, and my classmates stared hatefully at me as it gradually became clear that a reprobate sat among them. I even wondered if the teacher had selected my story just to teach me a shaming lesson, for in those days I was still capable of attributing those kinds of motivations to adults.

Kirshenbaum: By default. In the fifth grade we auditioned for the school choir. It wasn’t really an audition because the choir was the fifth grade. There were two performances of the Winter Pageant. One in the afternoon right before Christmas vacation for the younger students, and one that night for the parents and the older kids. The first week of school, the music teacher called us up, one at a time, to where she sat at the piano; we’d sing the first stanza of "Happy Birthday" and she then designated us "altos" or "sopranos." The whole raison d’etre of the fifth grade was the choir. The Winter Pageant was breathtakingly beautiful and now I was going to be in it, on stage, instead of part of the audience. Except when I sang "Happy Birthday," the music teacher––Miss Gilbert, her I remember––said, No. Neither alto nor soprano, I could not be part of the choir, I would throw everyone around me off-key, she explained. Choir practice was on Fridays mornings, at 11 a.m., and on that first Friday when everyone went to the Music Room, my teacher took me to the Art Room. There, the art teacher showed me how to fold the silver foiled paper into fourths and then again, and snip, snip, and behold! A snowflake. Every Friday, for one hour, for three months, I made snowflakes.

––Who was your closest competition?

Beller: There was no direct competition.

Furst: No one. Our Dolphin lapped everybody.

Graver: The kids who won first and second place.

King: Some kid. I doubt there was anyone famous in my third grade class.

Kirshenbaum: I had no competition. I was the only fifth grader unable to carry a tune.

––What were some of the perks of winning?

––What were some of the perks of winning?

Beller: You got a patch. You got one for every level. So this was the last patch—It said Tennis VI, and had the camp logo. I think if I had gotten it early in the season there would have been an outcry of protest that a dinker got it, but it was right before the end of camp, real life was about recommence.

Furst: A satisfying, and completely unearned, sense of accomplishment. Also, the public shame of having displayed an unseemly amount of mother-love. And then, also, the warm glow of knowing my mother knew I loved her.

Graver: I got published in The North Adams Transcript at the age of seven. And sold my soul. That all made an impression on me, but especially the selling your soul part. I was taken aback by being asked to change the ending, though it didn’t occur to me in any serious way to consider saying no. It was an interesting introduction to the world of publishing.

King: The prize was not actually a ribbon or certificate, but a fancy die-cut model of a haunted house. It was from Hallmark, and I thought it was fantastic: incredibly intricate in all its details and in its clever use of folded cardboard. The teacher had already put the thing together, and when she unveiled it and said it would be the prize for the story contest, I knew I wanted it, whatever the cost. In fact, I’m not terribly materialistic, and this may be the incident of greatest covetousness in my entire life, so it was something of an aberration, but at the same time it was very real.

I suppose I could claim I was overcompensating because we’d just moved to that school district, and the kids in my new school had all learned multiplication, which hadn’t been taught yet at my previous school; so I entered third grade as one of the dumb kids. But at the same time, I was reasonably well liked. I had friends and did Cub Scouts and for a while our family went to church. So I really can’t lay this at a sense of inadequacy or social insecurity. I just had to have that haunted house. Desire’s such an odd thing.

Kirshenbaum: In this case, I suppose I could say there were perks to losing. I learned to cut a mean snowflake. And I could push it and say it helped me develop a thicker skin and fostered a sense of individuality, especially when on the day of the pageant the fifth grade filed into the auditorium. We took our seats, and then after the principal made a speech, Miss Gilbert blew a C-sharp on her pitch pipe and the fifth grade rose up and took their place on the stage, leaving me in the midst of three rows of empty seats. But probably the only real perk was that I didn’t have to look at that bitch of a music teacher every week.

––Where do you think this ribbon or certificate is today?

––Where do you think this ribbon or certificate is today?

Beller: I know exactly where it is, in the top drawer of a desk at my mother’s house, my old desk, where I have a bunch of other childhood memorabilia. I’m glad I still have it. It’s a fair, sea-gray shade of blue, a hopeful color.

Furst: In a Phillips cigar box, along with my childhood bottle cap collection, somewhere in my mother’s unfinished attic.

Graver: I’d like to say I have no idea, that it’s been lost in the detritus of the past, replaced by more substantial honors, or by my ability to transcend the need for them. In fact, it’s on the mantelpiece in my study. For years, it was in a drawer in my parents’ house, but recently I found it and took it home, sort of as a joke and sort of because . . . why? Well, it’s hard to keep writing when the economy is collapsing and Americans don’t read fiction and you’ve made the mistake of joining Facebook and can sit at your computer reading about what 150 of your so-called friends are doing right now. It’s a framed certificate with my name in very nice calligraphy. Inside the glass of the frame is a little bookmark with an embroidered poem on it called “Little Things,” by Grace Haines. The prize is sweet and kitschy and, because of the story behind the story, complicated—all of which I like.

King: Can we please stop talking about the darn prize? That’s not the point! Because after that humiliation, everything changed for me. I wrote no more fiction, and I put on weight. I didn’t learn my multiplication tables for another decade or so, and my mother’s drinking escalated. I didn’t get into Yale. I traveled across country and worked in a factory, loitered around the men’s rooms of public parks and took acid and smoked pot. The one thing I can say is that I worked on my people skills, since it seemed that getting others to like me was my one ace in the hole. And I did fall in love. But even now, I trace every disappointment and failure I’ve experienced—all those nights I drank too much or too little, my tendency toward malapropisms and Freudian slips and misguided fashion choices, my failed painting career and a stammer I developed between 1996 and 1999, even the bouts of erectile dysfunction I may or may not from time to time experience—I blame all of it on the deep moral shame of October 31, 1963, and I’m still working through it. With the help of my therapist I’ve begun to acknowledge that the teacher may not have cared that an eight-year-old borrowed a plot point. That perhaps she gave me that prize because she liked the writing or the characters or the symbolism or the mise-en-scène; or because my story was the most ambitious that third grade class produced. I struggle to believe that, and I thank all the loved ones who support me in that belief. But it was only after my novel—invented, thankfully, out of my own head—won a commendation or two that I began really to heal. If, indeed, I have begun to heal.

Kirshenbaum: Indelibly etched in memory and being worked out on the analyst’s couch? When I was getting ready to go to college, my mother gave me a box filled with my grade school memorabilia. I sifted through my report cards, finger painting from kindergarten, a poem a wrote in third grade, and then there was the program for the Winter Pageant: Snowflakes by Binnie Kirshenbaum. I sort of laughed and sort of didn’t, and I threw it all in the garbage. So unless someone else from my fifth grade class saved their Winter Pageant program, it long ago biodegraded in a landfill somewhere.

Jaime Clarke is the author of the novel WE’RE SO FAMOUS, editor of DON’T YOU FORGET ABOUT ME: CONTEMPORARY WRITERS ON THE FILMS OF JOHN HUGHES, and co-founder of POST ROAD, a national literary magazine based out of New York and Boston