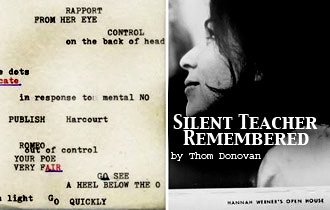

Silent Teacher Remembered: Hannah Weiner’s Open House

20.12.07

Silent Teacher Remembered

Silent Teacher Remembered

A Reading for Hannah Weiner’s Open House

November 28th, 2007

St. Mark’s Church

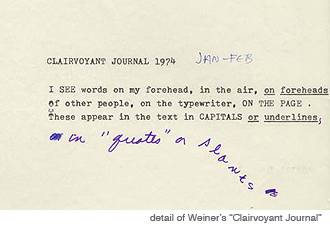

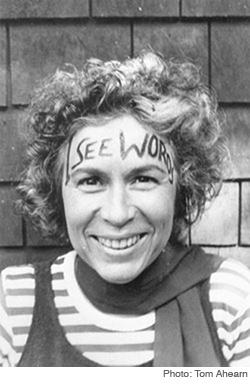

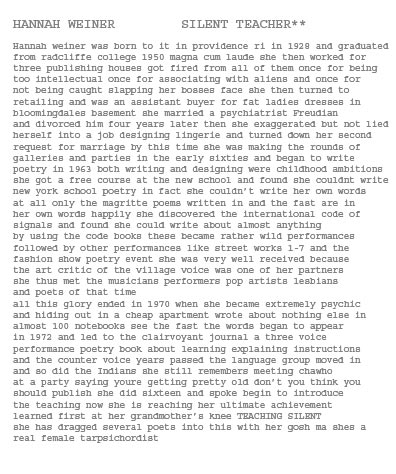

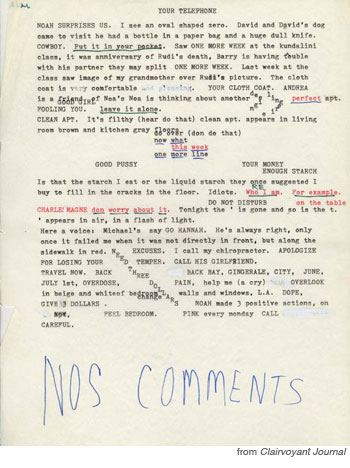

In the early 1970s poet, “live” artist, lingerie designer, friend to Downtown fellow travelers and self-professed “clairvoyant” journalist and “silent teacher” Hannah Weiner began to have hallucinatory visions of words. The first page of Weiner’s 1974 book, Clairvoyant Journal, explains the situation succinctly:

I SEE words on my forehead In THE AIR

on other people on the typewriter on the

page These appear in the text in CAPITALS

or italics

Such visionary experiences, shared by few others throughout recorded history, were celebrated this past Wednesday, November 28th 2007 at St. Mark’s Poetry Project during a night curated by Poetry Project director, Stacy Szymaszek. The gathering of poets, artists, friends, acolytes and scholars of Weiner’s work came about around the recent publication of Hannah Weiner’s Open House, a selection of Weiner’s work edited, introduced, designed and published by Patrick Durgin through his distinguished Kenning Editions (kenningeditions.com). That 2007 should mark the tenth anniversary of Weiner’s passing also offered a fitting moment for commemoration, reflection and tribute.

To begin the evening, Szymaszek handed the mic off to Durgin, who proceeded to talk about an aspect of Open House’s publication he hadn’t discussed publicly before: the book’s design. In his address, Durgin spoke specifically about how he and a co-designer, Jeff Clark, were waylaid in their plans only to arrive at a design more fitting the careful errancies of Weiner’s work. As Durgin himself explains in an entry posted to his blog, Da Crouton:

Clearly it requires great care to set the type in a book of Weiner’s work, especially her work from the 1970s; and I address this in the introduction. But I simply didn’t have the mechanical reasoning required also to design the cover. And so I collaborated with Jeff Clark, aka Quemadura. We decided to replicate, at an elegant angle, the invitation Weiner printed for her “Open House” event. That’d be the front cover. We’d use a dull matte gloss on the front cover and the spine, and use what they call a “spot varnish” on the text. The intended effect was to make the text gleam. The back cover, filled with blurb, was printed in reverse—the white background is glossy and the text has a duller matte finish. All of this trickery cost the equivalent of printing a full color cover, so it’d at least be nice to see it pay off somehow. When the books came back from the printer, though, the effect was so subtle that it goes unnoticed—some texture would have helped.

However, I gradually noticed that the ultra-high-contrast black and white, the negative and positive and other bogus oppositions are undercut by the reverse patina, which by chance manages to render the blacks a very dark grey. If you hold it at the proper angle, that is.*

I liked this admission of fortuitous miscalculation, as it attests to the special care Durgin gives to whatever he publishes. This admission also seemed significant since Weiner herself was involved with design through her employment by the lingerie trade and publishing industry, and was especially subtle and careful in the ways she typed her manuscripts where words sprawl across the page in three different type faces, forming less a linear prosody than a total visual field felt in its typographic immediacy. As Durgin also recognized, “when we encounter Weiner’s work, we are met with the shocking recognition that the autonomy of lived experience is a pernicious hoax”. This observation, characteristically well-put by Durgin, may sum up Weiner’s position as she continuously acted as a medium for perceptions, information, encounters with other people, communities, free-floating signs, signals and “intermedia”—the stuff of “lived experience”!—throughout her career.

I liked this admission of fortuitous miscalculation, as it attests to the special care Durgin gives to whatever he publishes. This admission also seemed significant since Weiner herself was involved with design through her employment by the lingerie trade and publishing industry, and was especially subtle and careful in the ways she typed her manuscripts where words sprawl across the page in three different type faces, forming less a linear prosody than a total visual field felt in its typographic immediacy. As Durgin also recognized, “when we encounter Weiner’s work, we are met with the shocking recognition that the autonomy of lived experience is a pernicious hoax”. This observation, characteristically well-put by Durgin, may sum up Weiner’s position as she continuously acted as a medium for perceptions, information, encounters with other people, communities, free-floating signs, signals and “intermedia”—the stuff of “lived experience”!—throughout her career.

Taking the mic after Durgin was Laura Elrick and Roberto Toscano, poets currently residing in New York. They staged an early poem from Weiner’s Code Poems entitled “Romeo and Juliet”. In “Romeo and Juliet,” the Shakespearian couple’s amorous encounter is retold hilariously through “code,” specifically the semaphore alphabets used by the British and American navies. On the cover of Weiner’s original book the words “Not Yet. By and Bye,” “Never,” “Not Often. Seldom,” “Soon. Shortly,” “Ago. Since,” and “At Once. Now. This Time” appear spinning around a Mandala whose center reads “When Does It Or You Begin?”

In Elrick’s and Toscano’s staging of the poem the couple paced around the audience at St. Mark’s speaking their lines through walkie-talkies. Through this staging the audience could feel the quirky effects of Weiner’s version of Romeo and Juliet, as the sexual foreplay of the couple is imagined as two ships meeting at sea, sheepishly negotiating their gam through “friendly fire”:

TU Romeo: Have you a clean bill of health?

GHI You are in a very fair berth

GIA Juliet: This is my best point

SHJ Some swell

XOR Romeo: Thank you

GDS May I begin to?

GIT Juliet: The sooner the better

MFO Romeo: Entrance is difficult

MFD Juliet: Try to enter

KZU Romeo: I am in difficulties; direct me how to steer

OOX Juliet: You should swing and enter stern first

HBK Romeo: What is the nature of the bottom or what kind of bottom have you?

HAY Juliet: Double bottom

FHR Romeo: Stern way. Going astern (Open House, 38)

Following Elrick and Toscano was art critic John Perreault, a friend and colleague of Weiner’s who participated in Weiner’s 1969 “Open House,” the event for which Durgin’s collection is named, and which also featured Vito Acconci and Arakawa among other notable artists. In Perreault’s presentation he highlighted Weiner’s involvement with the performance-based climate of the 1960s and 1970s. In addition to reenacting the semaphore language of Weiner’s Code Poems by waving flags fashioned from dish-rags, Perreault recalled some of Weiner’s other performance works. These works included a collaborative “Fashion Show Poetry Event” where Weiner presented a cape with hundreds of pockets proclaiming “one should wear their own luggage.” A piece where Weiner waited in a specified location in New York City to meet her doppelganger, Hannah Weiner, a “psychodramatist” sharing Weiner’s name who she found in the phone book. As Perreault noted, Weiner’s name-sake never showed-up for the meeting. A work where the audience viewed a ping-pong match from the side of only one player, and a similar work where the audience was asked to listen to one side of a phone conversation. Another where Weiner waited on a street corner dressed as a prostitute, only instead of soliciting customers she threw “stars” onto the sidewalk. The last of Weiner’s performances described by Perreault was one in which Weiner distributed free hotdogs in front of a hotdog stand called “Weiner’s Wieners” and a durational performance involving a long, extemporized speech about “anxiety”.

Following Elrick and Toscano was art critic John Perreault, a friend and colleague of Weiner’s who participated in Weiner’s 1969 “Open House,” the event for which Durgin’s collection is named, and which also featured Vito Acconci and Arakawa among other notable artists. In Perreault’s presentation he highlighted Weiner’s involvement with the performance-based climate of the 1960s and 1970s. In addition to reenacting the semaphore language of Weiner’s Code Poems by waving flags fashioned from dish-rags, Perreault recalled some of Weiner’s other performance works. These works included a collaborative “Fashion Show Poetry Event” where Weiner presented a cape with hundreds of pockets proclaiming “one should wear their own luggage.” A piece where Weiner waited in a specified location in New York City to meet her doppelganger, Hannah Weiner, a “psychodramatist” sharing Weiner’s name who she found in the phone book. As Perreault noted, Weiner’s name-sake never showed-up for the meeting. A work where the audience viewed a ping-pong match from the side of only one player, and a similar work where the audience was asked to listen to one side of a phone conversation. Another where Weiner waited on a street corner dressed as a prostitute, only instead of soliciting customers she threw “stars” onto the sidewalk. The last of Weiner’s performances described by Perreault was one in which Weiner distributed free hotdogs in front of a hotdog stand called “Weiner’s Wieners” and a durational performance involving a long, extemporized speech about “anxiety”.

In the next two presentations, Weiner’s three-time publisher and tireless supporter, James Sherry, publisher of Roof Books and mastermind behind the ongoing Segue reading series (now housed at Bowery Poetry Club) talked about his relationship with Weiner during the preparation of her book, Little Books/Indians. To close, he read a poem by Weiner invoking the American Indian Movement (AIM) leader, Leonard Peltier, an acquaintance of Weiner’s who remains imprisoned to this day accused of murder and treason by the U.S. government.

In her presentation, poet Anne Tardos read a selection from Weiner’s early 70’s diary, The Fast, in which Weiner first begins to have the visionary experiences that would lead to her later “clairvoyant” writings. The Fast takes place over a month-long period and is both a lived (that is, suffered) durational performance and the text that survives the performance through Lewis Warsh’s United Artist Books. Hearing The Fast read aloud, I was struck by the urgency of Weiner’s bodily and psychic circumstances as she navigated consumer culture, purchasing ordinary household items from the supermarket that would either cause her pain or offer her relief from her personal hell (The Fast was originally subtitled “The Hell Manuscript”). During her Bardo Weiner feels, synaesthesiacally, colors emanating from objects in her environment. That Weiner’s “durational performance” was terminated by cops breaking down the door of her apartment punctuates the importance of The Fast as a transitional point in Weiner’s “transformation” from equipped New York School poet to postmodern Kabbalist.

I secured a detail watch over my body and then continued. In the groin area I saw a whole picture superimposed on my body. Red and green and black lines and dots going from one side down the urinary tract and the ovaries. It was a cartoon superimposition in the same place I months later saw the clock image which I interpreted as meaning this will take time. I was pretty impressed with that diagram and kept asking the so-called I myself spirit, a light outline of a face smoking a pipe, what to do. I had previously seen a picture of my spine superimposed on a drawing on the wall. The other things I saw images of on me were the instruments of my lingerie trade, a plastic ruler, a stapler, staples (in the knotted muscles of my hands), scissors and pins. This amused me and I made them go away with my mind or with the little words my mind taught me. (The Fast, 36)

Following Tardos, I read a statement I’d written specifically for the tribute, addressing my sense of Weiner’s privileged status as an “innocent,” one who “undergoes” the sensations and feelings of others in her world towards ethical and political consequence. To support this intuition, I read specifically from Weiner’s early 1980s book, Spoke, published by Douglas Messerli’s Sun & Moon Press. In a statement Weiner wrote for Poetics Journal (ed. Lyn Hejinian and Barrett Watten), Weiner explains that Spoke is a work of “transference”. The transferential environment that is Spoke is underscored by Weiner’s use of the personal pronoun “I” to identify with everyday objects (toilet paper, blankets, etc.) as well as with contemporary personages as opposed to each other as Ronald Reagan and Leonard Peltier. Through such uses of the “I,” Weiner presents a field created by words where things become their opposite, opposing energies interrelate, conflict, and, indeed, transfer. In consequence, Weiner brings a “psychoanalytic” phenomena (transference) to political-ethical tragedy—the further destruction of American politics by Reagan’s presidency, the ongoing plight of Native Americans under the thumb of the U.S. federal government.

Clairvoyantly, Andrew Levy, a close friend of Weiner’s in her later years (he knew her from 1985 on), chose to read overlapping passages from Spoke that also underscored Weiner’s commitments to ethical and political urgencies. He read these passages in tandem, reminiscing about Weiner’s love for popular culture, and especially for children’s cartoons. In closing, Levy read a longer passage from Weiner’s poem, “Radcliffe and Guatemalan Women,” where Weiner alternates lines lifted from writings by Radcliffe alumnae (Weiner herself was an alumna) and women workers in Guatemala during the 1980s. Here, it is striking how such a simple procedure—the juxtaposition of two texts from wildly different and conflicting contexts—can produce such an intense and angering effect in the right hands.

Clairvoyantly, Andrew Levy, a close friend of Weiner’s in her later years (he knew her from 1985 on), chose to read overlapping passages from Spoke that also underscored Weiner’s commitments to ethical and political urgencies. He read these passages in tandem, reminiscing about Weiner’s love for popular culture, and especially for children’s cartoons. In closing, Levy read a longer passage from Weiner’s poem, “Radcliffe and Guatemalan Women,” where Weiner alternates lines lifted from writings by Radcliffe alumnae (Weiner herself was an alumna) and women workers in Guatemala during the 1980s. Here, it is striking how such a simple procedure—the juxtaposition of two texts from wildly different and conflicting contexts—can produce such an intense and angering effect in the right hands.

For us, the earth is sacred

We will succeed

When I was fifteen, in 1973, my father was arrested for the first time

They can call on a lot of PHD’s for technical abilities

It was all the rich who persecuted us campesinos

Let’s make the most of them

He suffered a lot of pain and could not work in the fields

For all those women throughout the world who are torn by political and economic

revolution and by attacks against home and family

We taught the children how to guard the road during the day

A truly liberating education

Soon afterward my father was killed… burned alive inside the embassy

With an appreciation of the humanistic worlds (Open House, 95)

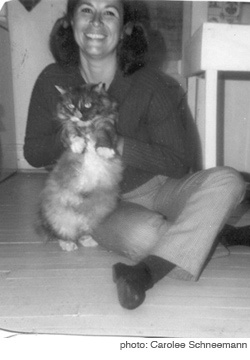

Before intermission, Carolee Schneemann presented a slide-show in which she “waited” for slides of Weiner to appear. In the meantime, Schneemann appeared in the slides with various lovers (many of whom she asked the audience to identify) and friends shared by herself and Weiner. I loved Schneemann’s performance for its playfulness and the dialogue it established with the audience. In this performance there was the air of a “trip down memory lane,” as Schneemann seemed surprised by the ordering of the slides showing herself and others at gatherings in the 1960s and 70s, having fun and hanging-out. Often, when Schneemann would not remember someone’s name (or claimed not to) someone in the audience would blurt out the name, exciting other audience members to do the same. When Weiner finally did appear in the slides, Schnemann recalled the photos were taken on a day when Weiner planned to cook dinner for others, and offered that Weiner was a great cook when she put in the effort. Among these photos were some of Weiner and Schneemann with their cats. Schneemann’s performance ended with a loud “meow” evoking the meeting of her cat with Weiner’s and joyously affirming the affinity and friendship of the two artists.

After the intermission, Weiner’s friend and literary executor, Charles Bernstein, his wife Susan Bee, and their daughter Emma Bee Bernstein, performed a selection from Clairvoyant Journal in the style of a performance Weiner and two co-performers gave in the mid-1970s at St. Mark’s Church “from the journal in May” (a recording of which is published by Durgin’s Kenning Editions). To this practical reenactment, the Bee-Bernsteins brought much of the spirit of Weiner’s 1970’s performance—laughter, overlapping words, outbursts of frustration at not being able to follow the score, and all. Afterwards, Charles Bernstein addressed the gathering, expressing his appreciation for Durgin’s efforts, as well as for the presenters and everyone assembled. That Bernstein acknowledged the many who would have liked to have presented at the tribute but did not attested to Weiner’s large sphere of friendship and influence. That he also expressed Weiner would have liked that so many were included in the event who did not know her, recalled her openness to new experiences and to making new friends.

After the intermission, Weiner’s friend and literary executor, Charles Bernstein, his wife Susan Bee, and their daughter Emma Bee Bernstein, performed a selection from Clairvoyant Journal in the style of a performance Weiner and two co-performers gave in the mid-1970s at St. Mark’s Church “from the journal in May” (a recording of which is published by Durgin’s Kenning Editions). To this practical reenactment, the Bee-Bernsteins brought much of the spirit of Weiner’s 1970’s performance—laughter, overlapping words, outbursts of frustration at not being able to follow the score, and all. Afterwards, Charles Bernstein addressed the gathering, expressing his appreciation for Durgin’s efforts, as well as for the presenters and everyone assembled. That Bernstein acknowledged the many who would have liked to have presented at the tribute but did not attested to Weiner’s large sphere of friendship and influence. That he also expressed Weiner would have liked that so many were included in the event who did not know her, recalled her openness to new experiences and to making new friends.

Following the Bee-Bernsteins, Lewis Warsh also read from Clairoyant Journal, a work his Angel Hair press published in 1974 with the help of Barrett Watten, who typeset the typographically intricate manuscript from the geographic remove of San Francisco. After Warsh, another of Weiner’s younger publishers followed, New York-based poet Lee Ann Brown, whose Tender Buttons published Weiner’s sileNt teachers/remeMbered sequel in 1993. Brown read passages from the Tender Buttons book, including Weiner’s candid biography statement in which she humorously recounts her life as a writer.

After Brown, scholar Kaplan Harris presented a previously unknown document from Radcliffe College’s alumni office archives. Kaplan’s offerings, from a questionnaire sent to Weiner by Radcliffe College in 1974 just after the completion of her Clairvoyant Journal, show Weiner having fun with the questionnaire format, a format intended to solicit information and patronage from Radcliffe alumnae. After the question “Describe work of past years” and the heading “title and position” Weiner wrote, “ DESIGNER of LADIES / UNDERWEAR 1959-1972 / Now I write full time / I stopped working in 1973 BECAUSE there was no more work at my job. FIRED.” Under the question “What experiments in your life have had a major effect on the choices you have made? List below briefly.” Weiner wrote in line number one, “TAKING ACID, becoming a 39 yr old hippie” reversing this answer with her answer in line number two, “STARTING TO WRITE + PERFORM at 34.” In line number three Weiner wrote, “SEEING WORDS ON MYSELF IN THE AIR, EVERYWHERE at 44.” In response to the question “Everyone’s life is somewhat different from the way she had expected it to be at a previous time. Could you list, briefly, some of the major differences between your life now and what you had expected it would be at the time of your graduation from college?” Weiner wrote, “I did not expect to have any psychic experiences TOO MANY. / The words in capitals are the ones I see. Psychic experiences begin at 40. I also / did not expect to WRITE POEMS, or do poetry events / DELIGHTFUL. I never expected to SEE WORDS.”

After Brown, scholar Kaplan Harris presented a previously unknown document from Radcliffe College’s alumni office archives. Kaplan’s offerings, from a questionnaire sent to Weiner by Radcliffe College in 1974 just after the completion of her Clairvoyant Journal, show Weiner having fun with the questionnaire format, a format intended to solicit information and patronage from Radcliffe alumnae. After the question “Describe work of past years” and the heading “title and position” Weiner wrote, “ DESIGNER of LADIES / UNDERWEAR 1959-1972 / Now I write full time / I stopped working in 1973 BECAUSE there was no more work at my job. FIRED.” Under the question “What experiments in your life have had a major effect on the choices you have made? List below briefly.” Weiner wrote in line number one, “TAKING ACID, becoming a 39 yr old hippie” reversing this answer with her answer in line number two, “STARTING TO WRITE + PERFORM at 34.” In line number three Weiner wrote, “SEEING WORDS ON MYSELF IN THE AIR, EVERYWHERE at 44.” In response to the question “Everyone’s life is somewhat different from the way she had expected it to be at a previous time. Could you list, briefly, some of the major differences between your life now and what you had expected it would be at the time of your graduation from college?” Weiner wrote, “I did not expect to have any psychic experiences TOO MANY. / The words in capitals are the ones I see. Psychic experiences begin at 40. I also / did not expect to WRITE POEMS, or do poetry events / DELIGHTFUL. I never expected to SEE WORDS.”

The final two presentations were given by Weiner’s friend from early on in her adult life, the poet Jerome Rothenberg, and Weiner’s best friend in her later years (1980’s on), the artist Barbara Rosenthal. In his presentation, Rothenberg covered a topic especially sensitive for the gathered, and to the discourse surrounding Weiner’s work at large: the relationship between Weiner’s “transformation” into “clairvoyant” journalist and her use of psychotropic drugs like LSD in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. Rothenberg addressed what one friend has called “the elephant in the room” of Hannah Weiner’s legacy in an especially sensitive way. The way he did this was to first present Weiner as he and his wife Diane Rothenberg knew her, before her use of acid. His depiction was of an entirely world-weary soul, yet responsible, professional even in her work designing lingerie. The transformation that occurred in Weiner was no doubt influenced by LSD, but also a response to the vital literary and visual arts communities flourishing Downtown in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Insofar as Weiner did “TOO MUCH ACID” (Weiner’s own words from Clairvoyant Journal) she was, in her own way, a victim of the climate of radical experimentation during the psychedelic era. Inasmuch as Weiner was a gifted, sensitive and educated person, she brought to her LSD trips insights about “the Word” as visible fact among a much wider conversation, a continuum of mainstream and marginal culture workers and artists, what poet Robert Duncan called “ a symposium of the whole.” Appropriately, Rothenberg likened Weiner to William Blake, on whose birthday the St. Mark’s tribute fortuitously fell. Also, appropriately, Rothenberg put Weiner in a line of mystic visionaries including the Kabbalist Jewish mystic, Abraham Albulafia, and the Mexican shaman, Maria Sabrina, who also hallucinated words, in fact dreaming up an entire alphabet. Troubled by the sensational speculations since Weiner’s death about her “transformation” and demise, I and many others who feel close to her person and writings felt relieved by Rothenberg’s address, which directly confronted the problem of Weiner’s “clairvoyance” head-on in a caring way. To close, Rothenberg read a poem triangulating Weiner with Albulafia and Sabrina, paying tribute to all three visionaries through his own shamanistic poetic practice.

The final two presentations were given by Weiner’s friend from early on in her adult life, the poet Jerome Rothenberg, and Weiner’s best friend in her later years (1980’s on), the artist Barbara Rosenthal. In his presentation, Rothenberg covered a topic especially sensitive for the gathered, and to the discourse surrounding Weiner’s work at large: the relationship between Weiner’s “transformation” into “clairvoyant” journalist and her use of psychotropic drugs like LSD in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. Rothenberg addressed what one friend has called “the elephant in the room” of Hannah Weiner’s legacy in an especially sensitive way. The way he did this was to first present Weiner as he and his wife Diane Rothenberg knew her, before her use of acid. His depiction was of an entirely world-weary soul, yet responsible, professional even in her work designing lingerie. The transformation that occurred in Weiner was no doubt influenced by LSD, but also a response to the vital literary and visual arts communities flourishing Downtown in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Insofar as Weiner did “TOO MUCH ACID” (Weiner’s own words from Clairvoyant Journal) she was, in her own way, a victim of the climate of radical experimentation during the psychedelic era. Inasmuch as Weiner was a gifted, sensitive and educated person, she brought to her LSD trips insights about “the Word” as visible fact among a much wider conversation, a continuum of mainstream and marginal culture workers and artists, what poet Robert Duncan called “ a symposium of the whole.” Appropriately, Rothenberg likened Weiner to William Blake, on whose birthday the St. Mark’s tribute fortuitously fell. Also, appropriately, Rothenberg put Weiner in a line of mystic visionaries including the Kabbalist Jewish mystic, Abraham Albulafia, and the Mexican shaman, Maria Sabrina, who also hallucinated words, in fact dreaming up an entire alphabet. Troubled by the sensational speculations since Weiner’s death about her “transformation” and demise, I and many others who feel close to her person and writings felt relieved by Rothenberg’s address, which directly confronted the problem of Weiner’s “clairvoyance” head-on in a caring way. To close, Rothenberg read a poem triangulating Weiner with Albulafia and Sabrina, paying tribute to all three visionaries through his own shamanistic poetic practice.

Barbara Rosenthal provided some reminiscence about her friend, emphasizing her closeness to Weiner. In fact Rosenthal felt so close to Weiner she imagined Weiner as an older version of her self at the time the two were friends. Following this idea, Rosenthal presented a series of videos playing on Weiner’s identity in relation to her own. The first of these videos, Rock a’ Bye Rock Lobster, featured Rosenthal singing the traditional lullaby while rocking a lobster in her arms. To the line “Rock a’ bye lobster” she added “Rock a’ bye rock lobster”. In the soundtrack of the video, one first hears Rosenthal intoning the lullaby, then Weiner, in her thickest of Rhode Island accents. The difference is striking as a moment of misidentification, Rosenthal not quite becoming Weiner nor Weiner quite Rosenthal. In the second video, Colors and Auras, one sees Rosenthal and a young girl identifying paint colors and color auras on Rosenthal’s body. These shots are intermingled with shots of Weiner watching-over the identified, naming them herself in the soundtrack. In the final video, Semaphore Poems, Weiner is seen in a grassy field (the literalized “open field” of her manuscript pages?) waving semaphore flags. Nothing is heard in the soundtrack except for the sounds of a rustic setting, seemingly amidst the lush greenery of upstate New York or Western Massachusetts. Far in the distance one sees an aged Hannah Weiner waving flags, ever the “silent teacher” (one of Weiner’s names for her profession). While this video is restive, even meditative, it is also a ghostly trace of Weiner’s person, hard to make out in the distance.

Barbara Rosenthal provided some reminiscence about her friend, emphasizing her closeness to Weiner. In fact Rosenthal felt so close to Weiner she imagined Weiner as an older version of her self at the time the two were friends. Following this idea, Rosenthal presented a series of videos playing on Weiner’s identity in relation to her own. The first of these videos, Rock a’ Bye Rock Lobster, featured Rosenthal singing the traditional lullaby while rocking a lobster in her arms. To the line “Rock a’ bye lobster” she added “Rock a’ bye rock lobster”. In the soundtrack of the video, one first hears Rosenthal intoning the lullaby, then Weiner, in her thickest of Rhode Island accents. The difference is striking as a moment of misidentification, Rosenthal not quite becoming Weiner nor Weiner quite Rosenthal. In the second video, Colors and Auras, one sees Rosenthal and a young girl identifying paint colors and color auras on Rosenthal’s body. These shots are intermingled with shots of Weiner watching-over the identified, naming them herself in the soundtrack. In the final video, Semaphore Poems, Weiner is seen in a grassy field (the literalized “open field” of her manuscript pages?) waving semaphore flags. Nothing is heard in the soundtrack except for the sounds of a rustic setting, seemingly amidst the lush greenery of upstate New York or Western Massachusetts. Far in the distance one sees an aged Hannah Weiner waving flags, ever the “silent teacher” (one of Weiner’s names for her profession). While this video is restive, even meditative, it is also a ghostly trace of Weiner’s person, hard to make out in the distance.

“A Reading for Hannah Weiner’s Open House” at St. Mark’s Church was an unprecedented tribute for a most unprecedented person. Though many of the presenters and audience members persist among poetry communities embattled by lacks of funding and support by mainstream culture, the event was also a reminder that Weiner’s work is irreducible to poetry culture alone. That a relatively small group of poets continue to read and devote themselves to Weiner’s work within and without “the academy” is a blessing. But for me Weiner’s legacy raises a larger problem of why poetry and visual art in particular do not make better friends these days. Weiner’s colleague Vito Acconci, for one example, started his career as a poet, and successfully forayed into visual art, and eventually architecture and design as well. Likewise, Carolee Schneemann might be considered a text-based visual artist, if not a poet, as her engagement with a poet as antithetical to her own project as the hyper-masculinist Charles Olson suggests (see Schneemann’s “‘Maximus at Gloucester’: a Visit to Charles Olson” in her 2002 MIT Press book, Imaging Her Erotics). While Weiner’s work must continue to be studied and paid tribute to by poets, it also deserves the attention warranted by an Acconci or Schneeman after recent retrospection by curators, critics and art historians. Personally, I tried to link-up the St. Mark’s tribute to Weiner with the recent PERFORMA biennial, but to no avail. That my own efforts failed as a writer “commissioned” by PERFORMA (I wrote for PERFORMA’s Writing Live initiative this past November) attests to a considerable disjunct between poetry and visual arts cultures, a disjunct undoubtedly damaging to both. As Weiner’s work intends to be read on and off the page, made “live” and “seen,” I only hope that more tributes to Weiner will crop up in the near future, in any variety of hybrid forms, venues and contexts.

“A Reading for Hannah Weiner’s Open House” at St. Mark’s Church was an unprecedented tribute for a most unprecedented person. Though many of the presenters and audience members persist among poetry communities embattled by lacks of funding and support by mainstream culture, the event was also a reminder that Weiner’s work is irreducible to poetry culture alone. That a relatively small group of poets continue to read and devote themselves to Weiner’s work within and without “the academy” is a blessing. But for me Weiner’s legacy raises a larger problem of why poetry and visual art in particular do not make better friends these days. Weiner’s colleague Vito Acconci, for one example, started his career as a poet, and successfully forayed into visual art, and eventually architecture and design as well. Likewise, Carolee Schneemann might be considered a text-based visual artist, if not a poet, as her engagement with a poet as antithetical to her own project as the hyper-masculinist Charles Olson suggests (see Schneemann’s “‘Maximus at Gloucester’: a Visit to Charles Olson” in her 2002 MIT Press book, Imaging Her Erotics). While Weiner’s work must continue to be studied and paid tribute to by poets, it also deserves the attention warranted by an Acconci or Schneeman after recent retrospection by curators, critics and art historians. Personally, I tried to link-up the St. Mark’s tribute to Weiner with the recent PERFORMA biennial, but to no avail. That my own efforts failed as a writer “commissioned” by PERFORMA (I wrote for PERFORMA’s Writing Live initiative this past November) attests to a considerable disjunct between poetry and visual arts cultures, a disjunct undoubtedly damaging to both. As Weiner’s work intends to be read on and off the page, made “live” and “seen,” I only hope that more tributes to Weiner will crop up in the near future, in any variety of hybrid forms, venues and contexts.

––T.D.

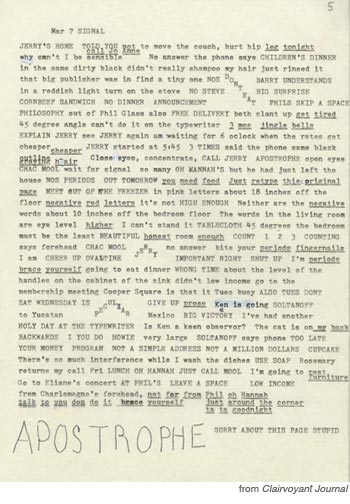

*Note we had similar problems as Patrick Durgin spoke of in laying out Weiner’s text here. Apologies, but the way our admin is designed, some of the quoted text will not come out correctly. Gaps become removed (as in the poem “Romeo and Juliet”), etc. And we have also italicized the text to show it’s a quotation, and that may also give an unitended effect. Just wish to point the reader to the illustrated texts that we have included to get the sense of the way the actual text looked as she inteded. There are more scanes here at Orpheus and more info on Weiner here.

Note on Images: Pg 1 combines the cover from Open House on right with text from Clairvoyant Journal. Pg 6 image “Hannah Weiner Silent Teacher”** is not from the original.