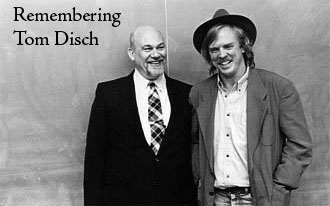

And Where Might That Be Now, Tom?

12.07.08

I just learned that Tom Disch, one of America’s funniest and most entertaining novelists and short story writers, died in New York a few days ago. I was extremely fond of Tom, who I met in 1990, when he was one of the first writers I invited to UCONN for a Visiting Writers series I had just started; and ever since discovering his work as a thirteen-year-old science fiction fan in the late Sixties, I have always been amazed by his productivity, his energy, and his creative joy. The first thing of his that I read was his paperback original novel, The Genocides, in which an awful middle-American family is casually decimated by a mindless alien race; not surprisingly, in Tom’s version of the universe anyway, the mindless alien race triumphs, and the awful family just does as it should do—dies horribly. Tom’s biggest obstacle in life was probably the intrepid stupidity of science fiction fans and literary critics, who simply didn’t get him. He annoyed people, as writers are supposed to do; and obstreperously set about upsetting all those boring unexamined assumptions that clog our minds and media—about the genres he loved, the religions he loathed, and even the literary lions he didn’t feel should be lionized. (One of his funniest essay titles was “Our Embarrassing Ancestor: Edgar Allan Poe.”) To this day, the boring people who spend their time in London and New York foraging for reputations offered him nothing but blithe disregard. It made him irritable; he often got caught up in pointless vendettas against people who cared for him; and, as a result, he wasn’t always an easy person to correspond with, or to speak with on the phone. In person, however, Tom was always all charm.

I just learned that Tom Disch, one of America’s funniest and most entertaining novelists and short story writers, died in New York a few days ago. I was extremely fond of Tom, who I met in 1990, when he was one of the first writers I invited to UCONN for a Visiting Writers series I had just started; and ever since discovering his work as a thirteen-year-old science fiction fan in the late Sixties, I have always been amazed by his productivity, his energy, and his creative joy. The first thing of his that I read was his paperback original novel, The Genocides, in which an awful middle-American family is casually decimated by a mindless alien race; not surprisingly, in Tom’s version of the universe anyway, the mindless alien race triumphs, and the awful family just does as it should do—dies horribly. Tom’s biggest obstacle in life was probably the intrepid stupidity of science fiction fans and literary critics, who simply didn’t get him. He annoyed people, as writers are supposed to do; and obstreperously set about upsetting all those boring unexamined assumptions that clog our minds and media—about the genres he loved, the religions he loathed, and even the literary lions he didn’t feel should be lionized. (One of his funniest essay titles was “Our Embarrassing Ancestor: Edgar Allan Poe.”) To this day, the boring people who spend their time in London and New York foraging for reputations offered him nothing but blithe disregard. It made him irritable; he often got caught up in pointless vendettas against people who cared for him; and, as a result, he wasn’t always an easy person to correspond with, or to speak with on the phone. In person, however, Tom was always all charm.

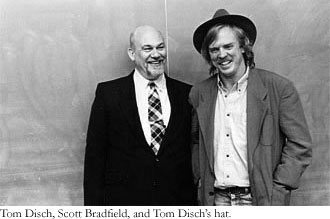

He was large, loud, quick, funny, honest, and thrilled by any form of attention. On several occasions, when I had him out for repeat guest appearances at UCONN, he delighted everybody he met. On one particularly memorable visit, he performed his one-act theatrical monologue in iambic pentameter, “The Cardinal Detoxes”, wearing a wide grey fedora and emoting like mad. This play constituted one of his many verbal assaults on religion, and for a while, he enjoyed (thoroughly) the sudden notoriety of having his play shut down by the Archdiocese of New York. On another occasion, he snored so loud in my guest bedroom that one of the wide-open windows slammed shut with a titanic crash. And every time we met, he talked beautifully and enthusiastically about books and art and music, and listened just as hard. Those of us who enjoyed his company when Tom was Tom were very lucky indeed.

I particularly remember the thick brilliant narratively- rapturous late horror-ish novels about those diabolical creatures of our world that Tom really feared: priests, substitute teachers, doctors, salesmen and, of course, Santa Claus. Then there were the vigorously intelligent and absorbing and always surprising stories: “Casablanca,” in which elderly tourists wander through a post-war landscape as vaguely and unresponsively as, well, tourists, snapping endless photos in a foreign land that never seems to surprise them; or “Fun With Your New Head,” a hype- ebullient sales patter hawking that most intimately- irreplacable item of designer apparel. (Tom worked on Madison Avenue for a few months way back in the Sixties and, like any writer worth his salt, milked that thin vein of experience for all it was worth.) Then there was “The Birds,” in which a pair of ducks suffer the worst fates our too-human world has to offer—or “The Shadow,” or “The Alien Shore,” or “102 H Bombs,” or “The Wall Around America”—so many great stories, and almost all of them neglected by the big boring anthologies that teach our high school and university students how not to read. Unlike the work of most modern writers, Tom’s books were good right from the very beginning with all those great titles: The Businessman: A Tale of Terror, The Brave Little Toaster, Camp Concentration, The Right Way to Figure Plumbing, Getting Into Death and Other Stories, and, my personal favorite, Here I Am, There You Are, Where Were We. His books and stories and poems were always thinking faster than you were from the very first sentence to the very last one. And this in a world where most books are too busily rethinking what was already thought better by somebody else.

Tom’s books were always excited about going somewhere new, much like Tom. It always amazed me how few people seemed to recognize his abilities and cantankerous talent, but then he didn’t always help himself, either. For while he loved the play and performance of most genres—sf and fantasy and gothic and horror and mysteries and opera and children’s bedtime stories—his work was too good for the boobs and tweenies who mindlessly hid away in them, like troglodytes in caves. Tom had a regal air; he expected to be respected; people, he seemed to think, were supposed to come to him, and he was probably (as usual) right. But I suspect that most of the people who truly loved Tom and understood him best never actually met him. They only needed to read him—and so experience that dependable repeatable sudden thrill of pleasure we all felt when opening up each new story, or essay, or poem by Tom in all his guises: Thomas M. Disch, Tom Disch, and even the ornate, publicity-shy Victorianish lady-novelist, Cassandra Knye.

Tom’s books were always excited about going somewhere new, much like Tom. It always amazed me how few people seemed to recognize his abilities and cantankerous talent, but then he didn’t always help himself, either. For while he loved the play and performance of most genres—sf and fantasy and gothic and horror and mysteries and opera and children’s bedtime stories—his work was too good for the boobs and tweenies who mindlessly hid away in them, like troglodytes in caves. Tom had a regal air; he expected to be respected; people, he seemed to think, were supposed to come to him, and he was probably (as usual) right. But I suspect that most of the people who truly loved Tom and understood him best never actually met him. They only needed to read him—and so experience that dependable repeatable sudden thrill of pleasure we all felt when opening up each new story, or essay, or poem by Tom in all his guises: Thomas M. Disch, Tom Disch, and even the ornate, publicity-shy Victorianish lady-novelist, Cassandra Knye.

It wasn’t easy being friends with Tom, and many years ago I gave up trying to speak with him on the phone. He was probably the worst phone conversationalist I have ever known—nothing but a dim uninvolved sequence of slow gentle deeply uninterested yesses and okays and well maybes, as if you were always on the verge of being judged or hung up on. When Tom was alone (but never, it seemed to me, when he had company) he was clearly deeply depressed. A few years ago, he lost his long time partner, Charles Naylor; and while Tom continued to produce fine books up until his death, those books continued to be disregarded. And there was talk that he might lose his rent-controlled book-lined apartment in Union Square. He was not ready to be that alone.

He was one of the few contemporary genre writers who deserves to be read in a hundred years. Maybe Bradbury, maybe Ballard and Moorcock, maybe Elmore Leonard, and very very maybe Tom Disch. He excelled at verse, essays, nasty and illuminating book reviews, teleplays, screenplays, the first interactive computer novel, children’s stories, opera librettos, you name it—roaming through all the sequestrated and self-obsessed literary wonderlands with an axe, chopping everything to bits and putting it back together in ways that pleased him (and, by default, his readers.) There will never be another Tom. I know that’s something they always say in these quickly-written eulogies by admirers and friends, but really, there never will be. We deserved to keep him longer.

Those who haven’t read Tom should try The Priest: A Gothic Romance, his best and most completely successful novel. And any collection of his short stories—he was easily one of the best and most inventive story writers of his generation. His very critical books on contemporary poetry and science fiction—The Castle of Indolence, and The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of—enraged the practitioners of both. And what can you say about that? Only: Good going, Tom.

I didn’t get many letters from Tom over the years, but there are two that I’ll always recall with pleasure. When my son was born, he sent us—out of the blue—a huge beagle-sized deer puppet, with the note: So now you’ll learn how to make animals talk just like your dad. (Tom was the only writer who responded favorably when I sent him what I considered my best book, Animal Planet.) And just a few years previously, after I wrote to say how sorry I was that his best novel, The Priest, had been ignored by so many people, he sent me a brief, self-illustrated post card. It read:

I blame Knopf, the Catholic Church, and God.

Yes, Tom. Me, too. As usual, you were right.