George Kuchar: an appreciation and resurrected (self) interview

30.09.11

I don’t recall the first time I saw one of George Kuchar’s movies, but I’m certain it must have been in the early 1970s at the Fox Venice Theatre, the legendary L.A. area grindhouse that introduced vast numbers of underground, cult and outlaw movies to an entire generation of young filmgoers. I want to think it was Portrait of Romona (1971), but it could have easily been any of several dozen 16mm shorts that George produced (either singly or with his twin brother Mike) starting in 1954 when the boys were a mere 12-years-old.

I don’t recall the first time I saw one of George Kuchar’s movies, but I’m certain it must have been in the early 1970s at the Fox Venice Theatre, the legendary L.A. area grindhouse that introduced vast numbers of underground, cult and outlaw movies to an entire generation of young filmgoers. I want to think it was Portrait of Romona (1971), but it could have easily been any of several dozen 16mm shorts that George produced (either singly or with his twin brother Mike) starting in 1954 when the boys were a mere 12-years-old.

What is remembered vividly about that first Kuchar movie is just how funny, outrageous and way over-the-top it seemed, a sensation that would persist and grow over the years through dozens of other films like Pagan Rhapsody (1974), The Devil’s Cleavage (1975), A Wild Night in El Reno (1977), The Nocturnal Immaculation (1980), Ascension of the Demonoids (1985) or, deliciously, The Deafening Goo (1989). Such overwrought titles reflect the satiric sensibility and playful irony that inform or, rather, run riot in all of his movies. They are in equal part homage to and parody of that greater, glittering artificiality that is the product of the Hollywood dream factory, a factory whose most sacred cows are viciously skewered and served piping hot off Kuchar’s cinemagraphic grill.

These are not in the strict sense films about film, but instead are movies about the cinematic imagination, specifically about pushing the limits of that imagination to their farthest and ultimately most (il)logical conclusion. In an effort to transcend (or, if you prefer, transgress) the stifling pieties of conventional Hollywood filmmaking, Kuchar produces something that is instantly recognizable, comfortingly familiar, yet still manages to be wholly subversive. Hollywood’s favored tropes and techniques are made grist for his low or no budget mill. Lush orchestral soundtracks, elaborate costumes and make-up, loving close-ups and epic panoramas are all systematically subverted, distorted, trashed and turned on their heads; conventional cinema’s verities are stripped of their sanctimony and seriousness, leaving us laughing at the hapless emperor in all his glorious and grainy nudity.

Like all great comedic directors, Kuchar tackles the big themes––love, sex, war and, of course, aliens from outer space––and he does it with a touch so light and so uniquely his own that he might easily be dubbed the Lubitsch of the underground. His work resembles the great Viennese director in its heartfelt celebration of the commonality of human frailty and the humor that ensues from our vainglorious attempts to depict it. The difference (and it’s an important one, separating as it does mainstream from underground) is Kuchar’s embrace of the absurd, his innate sarcasm and his almost obsessive adoration of pop culture.

The death of someone like George Kuchar diminishes more than an artistic community tragically short of revolutionary perspectives, it leaves us yearning for an artist who can articulate the absurd, the ludicrous, the crazy part of ourselves that was created by the movies we watched and the TV shows in whose flickering shadow we were formed.

The death of someone like George Kuchar diminishes more than an artistic community tragically short of revolutionary perspectives, it leaves us yearning for an artist who can articulate the absurd, the ludicrous, the crazy part of ourselves that was created by the movies we watched and the TV shows in whose flickering shadow we were formed.

* * * * * * * *

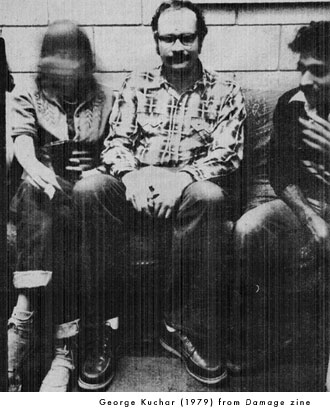

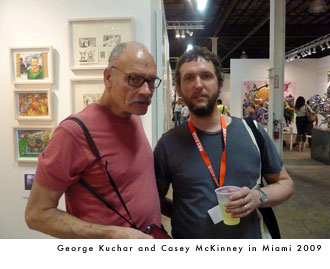

In 1977 I moved to San Francisco and found myself involved in the burgeoning punk scene. A few years later, mutatis mutandis, I started a small underground zine called Damage and, for the premier issue, I resolved to do an interview with George Kuchar who, conveniently enough, was teaching and making films at the nearby San Francisco Art Institute. We arranged to meet at a café in North Beach and I spent the days before the interview carefully crafting the questions I wanted to ask. When at last we sat down to do the interview, I pulled out my tape-recorder and watched in astonishment as George’s face drained of color. In a lifetime of doing interviews, I’ve never seen anyone so freaked. I dutifully asked my questions and he haltingly, hesitatingly answered almost monosyllabically. It was like pulling teeth and I was feeling increasingly desperate. To make matters worse, when I looked down at the tape recorder, I suddenly realized the cassette wasn’t turning. The batteries had died. “Oh man,” I moaned, “this is a total disaster.” George’s reaction was to instantly perk up, like he’d been born anew. “No problem,” he said, smiling widely, “no problem at all. I’ll tell you what, I’ll interview myself. I’ll do the whole thing. It’ll be great.” Well, I didn’t have much of a choice and, to tell the truth, the idea sounded way better than anything I could’ve come up with. George had only one stipulation, his autobiographic authorship was to remain strictly entre nous. “It’ll be our secret,” he said, chuckling, “just between you and me, you know?”

And I did know and now so do you. May he rest in peace forever and always and may the pagan angels sing him rhapsodically to sleep.

Link to George Kuchar films on the web: http://www.ubu.com/film/kuchar.html/

Why do you make movies?

Well, if I wasn’t spending money on movies, I’d be throwing it away on vices and dirty habits. Films help me get back on the track to creative and healthy living. This makes my ugly vices more fun to indulge in once I finished making a move.

What is your film background?

I attended movies early in my youth. I never did care for too much bright sun and dark places appealed to me. It was also fascinating to see grownups doing make-believe, like we kids did all the time. From going to the movies I acquired a certain film language that came in handy when I bought my own smaller-scale movie equipment. In this way you can be a kid all the time and not have such heavy equipment to lug around.

Do you incorporate your “ugly vices” into your movies?

Do you incorporate your “ugly vices” into your movies?

They are in there but they aren’t ugly on film. I don’t like making ugly things and I’m sure a lot of people don’t enjoy going to the cinema and paying to see ugliness. If that were so, then the theater manager would leave the houselights on to give the audience their money’s worth.

Why don’t you make films in Hollywood?

I like going to Hollywood to whore around. It’s fun to be cheap meat in that environment. I don’t drive a car so I’d be trapped in one spot if I lived there. I’d rather go to Salt Lake City and work with the Osmond family.

Do you like foreign films?

I always enjoyed the early Sophia Loren Italian movies where she played a fish saleslady and would get into fights with other salesladies and they’d smack each other across the face with mackerels. Foreign films also meant not so much an import of culture to American shores as, in those days, they were more like a tide of smut and lurid sexpots. They also were closer to comic books as written words appeared in the frame with the pictures. That is why they probably were so successful here in America.

Do you go to the movies regularly?

I go when I can but I don’t go every week. I guess it’s not one of my dirty habits. I think 70mm and Dolby sound are great, and I’d even like to see that combined with 3-D and Smell-o-Rama for an even bigger experience. William Castle should make another horror film with all of this plus throw in his “live” gimmicks. Maybe theaters could start giving dishes out once a week (like they did in the past) instead of stomach distress bags.

How do you use music in your films?

I never went along with the old saying that a film score is good only if you weren’t aware of it. I like to hear what I’m listening to. In the past I’d go to a movie if a certain composer did the score. Big orchestras with blatant love themes were a great experience and make you aware that people can create the silly on a grand scale. That is good for the spirit, as it’s less oppressive and leads to experimentation.

Did you ever make a musical?

Yes. A film I did with my students at the San Francisco Art Institute and called “Symphony for a Sinner” was, in some respects, a musical. Since none of the cast could sing it was humiliating for them at times. But, since I couldn’t write what are considered good lyrics, what’s the difference? If you want to make a musical, then make it. There are hundreds that have fine songs and singing and dancing. The other side of the coin should be experienced also.

Do you handle the choreography too?

Do you handle the choreography too?

Yes, as that is the thrill of making independent, underground movies. You get a chance to do everything you’ve ever wanted. In a way I’m like a blotter or a paper towel dripping with stains. Squeeze me and watch what spills out. I’ve absorbed enough Rita Hayworth and Rita Moreno to know what constitutes good choreography.

Do audiences object to this sort of digested regurgitations?

Certain individuals do, but they’re not much fun. What I regurgitate is a very definite part of me. What comes up is not only what went down but incorporates elements that were already sloshing around inside me.

What do you think of the punk scene?

Any movement that sanctifies dyed hair, ripped clothes, makeup and cigarette smoking is fine in my book, as these are the elements that make for good cinema.

What’s your feeling about porno films?

Movie theaters have always been pornographic as far as I’m concerned. They’re dark and there are lonely, repressed and bored people in the back rows and in the rest rooms. It was, in the Bronx anyway, a house of shame. Now that the “shame” is up there on the screen, it helps to alleviate the pressures that were building up in the audience. The most sexually explosive and gnawing feelings were generated by movies made by such people as Ozzie & Harriet Nelson with their son Ricky. It was such alien material that the viewer sought out and nurtured the most basic drives at the root of his being. It was either that or scream silently with a mouth full of popcorn. Ricky Nelson was too nice-looking to be sleeping in pajamas. A pervert was needed to direct this material.

What’s the key to unleashing filmic creativity?

Very little money, a miserable personal life and no script. If you don’t have these things, don’t despair: just pray for a flop so you can be kicked into the gutter with other imaginative minds. Remember…the vapors from a sewer always aim skyward. Chemicals in the body have a harder time being generated when everything is going smoothly. Filmic chaos and panic can be exhausting, but very seldom do they lead to constipation.