Supergroup in Reverse: The Afterlife of cLOUDDEAD

13.11.07

SUPERGROUP IN REVERSE:

SUPERGROUP IN REVERSE:

Yoni Wolf, Odd Nosdam, Doseone and the Afterlife of cLOUDDEAD

Every once in a great while when a band breaks up, it’s like a supergroup in reverse; each performer’s independent project is packed with an exactness of vision that seemed impossible in collaboration: as if Bob Dylan had always just been the guy who played rhythm guitar in the Traveling Willburys and then – Bam! – came out with Blonde on Blonde; a complete inversion of the rock archetype of Paul McCartney’s post-Beatle blandness.

Eccentric hip-hop trio, cLOUDDEAD, part of the Anticon collective, formed in Cincinnati in 1999 and relocated to Oakland together in 2001. Producer Odd Nosdam (David Madson) built murky soundscapes from archaic keyboards, flea market reel-to-reel tapes and a Roland SP-202 “Dr. Sample” while rappers Doseone (Adam Drucker) and Why? (Yoni Wolf) overlapped non-sequitur lyrics about paint-spattered eye-glasses, their neighborhoods and the universality of death. As self-described shut-ins who shared apartments in various permutations, on their albums they sound telepathically close: Why? and Doseone completing each others’ sentences while the production mirrors their hypnotic, sometimes morbid humor.

cLOUDDEAD split up in 2004 on the verge of something that might look like success if you squinted at it just right: a recording session with BBC tastemaker DJ John Peel, a remix by Boards of Canada and the cover of Wire magazine for their final album. The trio dissolved in hopes of preserving their increasingly acrimonious friendships and due to “creative differences”––a term that always recalls press release boilerplate, but which now, in retrospect, seems astonishingly true. After storming off in disparate artistic directions, each has created unusual, innovative work.

Most immediately striking is Yoni Wolf’s much ballyhooed departure from hip-hop into psych-folk-pop. Wolf surrendered his longtime rap moniker “Why?” which instead became a signifier for the band formed along with his brother, drummer Josiah Wolf, and fellow Cincinnati native, multi-instrumentalist Doug McDiarmid. Born Jonathon Wolf, he reverted back to an earlier nickname, yoni, the ancient Sanskrit word for vagina.

The band came into its own with 2005’s Elephant Eyelash, an album packed with up-tempo guitar hooks and a lyrical abundance that exceeds anything Wolf concocted in his previous collaborations. Its title is Wolf’s odd metaphor for male sexuality: imagine an enormous curved hair from a pachyderm’s eyelid, the length and shape of a boner.

If at first glance the lyrics seem non-sensical, an autopsy of the album’s exquisite corpse reveals a broken heart as the cause of death. In this baffling, romping elegy for a failed relationship, each song develops a curveball poetic conceit worthy of a slacker John Donne in a bomber jacket. Each line is an indelible image; specific, surreal, sensual, funny and emotionally engaging––“It moves slow like an exercise bike on an airport walkway.”

The song “Fall Saddles” is an epistle to Wolf’s father, a Messianic Jewish rabbi within a sect that believes Jesus was the messiah. In his youth, Yoni Wolf was forbidden to listen to secular music and, at age 15, when he first heard David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” it came as a transgressive revelation. Some of this mystique clings to Wolf’s approach to pop music while his themes of love, death and the afterlife (or probable lack thereof) seem handed down from his early infusion of sacred songs.

On “Light Leaves,” the album’s final track, Wolf asserts his desire to lie exposed and rotting on the ground after his death, rather than inside a casket. Thinking of the physical legacy he will leave behind, he includes a shout-out to the sperm shed in his various masturbation sessions: “My smaller selves down the sewer somewhere/under Berkeley, Cincinnati or on tour/(Airplane rears/and hotel lobby ladies rooms beware.)”

“I feel the more straight-up you are about the way you live and the secrets you have, the more you realize everyone is the same and has the same hang-ups and the less-likely you’re going to war with people,” Wolf said in an interview with the UK Guardian. “It’s political to me that I’m being so honest and saying shit to people that’s very personal to me; saying: ‘This is me, I jack off in the back of airplanes and so do you.”

During cLOUDDEAD, Yoni Wolf and Doseone would walk together through their East Oakland neighborhood or the BART train’s suburban end of the line, writing about whatever they saw. Always on the outskirts of hip-hop, cLOUDDEAD instead took the sound of the streets literally. On “Our Name,” the last track of their final album, a recording of a crack dealer berating Doseone’s neighbor serves as a stand-in for the band’s own internal conflicts. “And it ain’t no friendship, blood, cause I see when shit went down that what’s really going on behind all this is that dope. That’s what got everybody’s mind fucked up but my mind ain’t fucked up because I’m about to get my money.” Doseone’s lyrics lament the band’s demise: “Oh, what has/our name become…/a guilty pleasure/and Nosdam’s drums.”

On Odd Nosdam’s Level Live Wires, released in August, “Burner” begins with Nosdam sliding open his window after hearing a screech of tires while lying in bed. Shocked to see a burning SUV in front of his apartment, he splutters, accidentally dropping the weighty microphone of his 1970s Dictaphone, which can be heard dangling from its cord, scraping against the side of the house; the resulting track builds off the sound of the dying vehicle’s car alarm.

Urban field recordings are just one method Nosdam uses to bathe his tracks in a lived-in sound. He pours tape hiss, popping vinyl and the 60 cycles per second hum of electricity over compositions of singing Farfisa keyboards, throbbing drones and slumbering hip-hop beats. In the vast bulk of electronic music, soundwaves are confined to the airless interior of a laptop’s hard drive, never allowed to reverberate off the uneven surfaces a physical space; instead Nosdam creates a warm, spacious sound. It’s ambient hip-hop with a short attention span; each track punctuated with meticulous, ongoing tweaking of the layers upon layers of sound. Whenever a drone, a melody or a rhythm vanishes it reveals previously imperceptible elements in the mix.

During the recording of his 2005 album, also titled Burner, Nosdam lived upstairs from a group of East Oakland gang members. “Choke” includes samples of neighborhood gunfire; while “11th Avenue Freakout” uses the startled shouts of a beat-down’s victim as the launching point for a transcendent pop gem on par with Jackson 5’s “I Want You Back” or Talking Heads’ “Once in a Lifetime.” After listening to this track probably 200 times, my heart still thrills when I hear the incredible kick-off drum lick. Recorded in collaboration with Mike Patton and Why? band drummer Josiah Wolf, the song roars and crashes along in a state of exultant frustration before concluding with a remarkably self-recriminating vocal sample from someone who sounds like George Orwell: “I’d rather do something for peace but, alas, I am a coward; I prefer my comfortable home and I don’t do a thing. I hate myself.”

While Nosdam’s samples of neighborhood felonies could be construed as voyeuristic, it comes across as more autobiographical. “[That] vocal sample…speaks for people who passively sleepwalk through life,” Nosdam said in an interview with Undercover Magazine: “They know that there’s shit going on but they don’t act on it…Hopefully my meager little album can slap some sense into those people.” For anyone who has lived in a tough neighborhood, it recalls nights of listening to shouts and breaking glass; debating whether to call the police, go back to sleep or open the window and yell back.

cLOUDDEAD’s single “Dead Dogs Two” was marked “cLOUDDEAD 9 of 10” and the final album appropriately titled Ten. “For 20 days we were going to call the album Eminem,” Doseone said in a 2004 interview with ‘Sup Magazine. “This was our last record and I was all like, ‘Fuck it, man, let’s do that shit. It would be intense! Just think about what that speaks to, even if it’s a mistake and thousands of people buy it incorrectly! And they [Why? and Nosdam] were like, ‘They’ll sue us!’ and I was like, ‘No, just turn the E the other way!”

More than just a jab at the mainstream, Mr. Mathers played an inadvertent role in the formation of cLOUDDEAD. Yoni Wolf first approached Doseone after watching him battle Eminem in the second annual Scribble Jam freestyle competition held in Cincinnati in 1997. Wolf was as struck by Dose’s performance as he had been by that first transgressive blast of David Bowie a few years earlier.

“Despite all the meanmugging, [Eminem] and I had a beer between the semis and the finals,” Doseone said in an interview with cokemachineglow. “We were all cordial, both us respecting the other’s moxy. We were the two unknowns in the whole thing and I guess there was camaraderie in that.” Both competitors lost out to Chicago’s freestyle champ, JUICE, in a competition that Dose claims was weighted in favor of the marquee names and overly permissive of pre-written battle rhymes. He and Eminem exchanged phone numbers and CDs, although afterwards when Dose listened to Mather’s demo he was disappointed to hear the best of his competitor’s “freestyle” lines already recorded.

A magnetic and show-stealing performer, Doseone has said his original attraction to rap was as much about the “persona/ego projection” as a love of words, but this chance encounter with Yoni Wolf and the resulting friendship initiated his transition from the solitary bravado of battle rhymes into the collaborative ethos of Anticon.

Doseone’s most consistent collaboration has been with producer Jel as Themselves. The duo has joined forces with German indie rockers The Notwist as “13 & God” and with other musicians in their current project Subtle. Between 2004 and 2007, Doseone, solo and in these collective permutations, released six studio albums, two remix EPs, a spoken word CD, a book of poetry and a board game. Doseone is prolific, strange and onto something big. Two standout albums are his solo Ha (2005) and Subtle’s For Hero: For Fool (2006).

While Doseone’s early recordings feature a calmly taunting persona not unlike his freestyle battles, in his more recent albums this is just one of many characters elbowing their way to the forefront of his voice. On Ha’s “The Tale of the Private Mind,” Dose uses different vocal styles, microphones and filters to play the parts of a narrator, a scientist and a nine-year-old girl, describing the plight of an enormous brain (4’ x 5’) held against its will in a glass tank and, through chemical and psychological reinforcements, induced to think about nothing but finances. The track showcases his skill at arranging complex, seemingly cumbersome ideas and lyrics into tight pop phrasings.

On “By Horoscope Light I & II” from the same album, Dose disassembles his earlier rap battle persona. “Thank you, you’re too kind,” he shouts to an obviously canned loop of crowd cheers and then raps an apocalyptically bad newspaper astrology forecast: “My horoscope today was 1500 pages long/and in bullet form it read:/bad person, last chance/bad choice, no change.” After another rapid-fire verse, the production stops abruptly and Dose summarizes into the microphone of what sounds like a handheld tape recorder what the rap would have said if he’d bothered to finish it: “And the rest goes something like ‘In my vomit there was a last meal, a tin can, an old boot and a bunch of other stuff I never knew I had in me,” audibly crumpling the paper as he reads it. Layers of artifice are peeled back and arena rap collapses when faced with nauseating foreknowledge of one’s own doom.

On Subtle’s album For Hero: For Fool, Dose literalizes this vivisection of rappers in the song “Midas Gutz” about an ESPN reality TV show in which rappers, supervised and anesthetized by attendant doctors, cut open their own stomachs to determine which contestant has the most hardcore lengths of intestines. The panel of judges includes “Charles Bronson’s angry and gay only daughter/Ice Cube back from when he was hard/and a framed 8 x 10 of Joe Namath’s kneecaps.” The winner is set free in the Ozarks with a buck knife to test their survival skills.

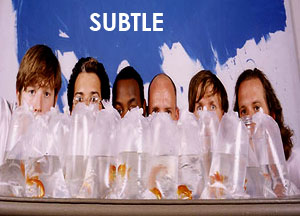

SUBTLE

SUBTLE

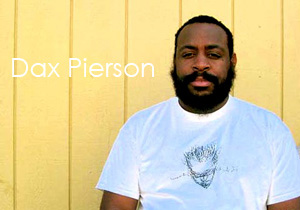

Doseone, Jeffrey Logan (Jel), Dax Pierson, Jordan Dalrymple, Martin Dowers, Alexander Kort

Capable of flipping from frantic aggression to paranoid breakbeat ballads, the six musicians in Subtle tackle autoharp, electric cello, guitar, horns, flute, a bevy of samplers, harmonica, and live and mechanized drums; without ever overcrowding a song. The group is known for its theatrical live shows that include plastic forks, cardboard Roman column facades, painted skulls and red pleather outfits.

Subtle’s albums, A New White and For Hero: For Fool, are the first two installments in a planned trilogy profiling the life and times of Hour Hero Yes, a struggling fictional rappers with a black and white zebra-striped face; an image that recalls both the role of race in rap and the bars of a cage. The storyline is adapted from a board game created by Doseone and his fiancee, illustrator Erin Perry, implying that a “rap career” may be based on little more than a role of the dice. When success arrives, as it does in the album’s disco-jock rock single, “The Mercury Craze,” it takes an unusual form: Hour Hero Yes learns he has the rarest blood type in the world and is wined and dined by a fabulously rich family with a terminally ill son.

Subtle’s own story is a similar mixture of success and tragedy. After a recent tour with TV on the Radio and having now signed to Lex Records (Madvillain, Dangermouse, a division of EMI) the group is receiving some much-deserved acclaim. Sadly, they are perhaps best known for their February 2005 tour van accident on a patch of Iowa black ice that left multi-instrumentalist Dax Pierson paralyzed from the shoulders down.

Although quadriplegic, confined to a wheelchair and unable to perform live, Pierson remains active in the group. The band waited for ten months until Pierson was able to return to Oakland from a treatment center in Texas to complete For Hero: For Fool on which he contributes backing vocals throughout. The album’s final track “The Ends” is built around recordings salvaged from Dax’s apartment, including an incredible “simultaneous piano and beatboxing one-take demo.” With the full accompaniment of the group, the finished version sounds like a more muscular take on Pinback’s math-pop, made more haunting by the likelihood that Dax will never play the piano again. In a fan’s concert video, the band introduces themselves backstage. “And Dax,” Doseone says, “who couldn’t be with us, although he’s always with us.” Pierson’s spinal cord will never regrow, but the band remains hopeful of further recovery through physical therapy.

There’s something about Subtle that has always seemed hopeful in the face of unlikely odds. Many of the band members met as clerks at Berkeley’s Amoeba Records during a time when Jel and Dose were stopping by frequently to shill their albums in order to pay rent; and then later working as clerks themselves. In promotional photos the band members––lifelong music fans, some of them in their mid-30s and 40s––look stunned to be finding success at a time when the opportunity seemed to have passed.

A TALE OF APES

For Hero: For Fool begins with a pair of tracks “A Tale of Apes I & II.” The first of which is a furious account of a gaudy stage show in which the performer unzips his ape suit to reveal an anchor tattoo, a pair of roller-skates and the knowledge that he has nothing worth saying; leading the crowd in a call and response of “Everything is empty.”

Both of Subtle’s albums have been followed by a remix-remake EP in which the album tracks are torn apart and re-conceived in collaboration with other artists. Yell&Ice, the remix companion to For Hero: For Fool, includes a one-off cLOUDDEAD reunion. “Falling,” their reinvention of “A Tale of Apes I,” is surely the clubbiest track the group has ever produced; its dancefloor synths are anchored by Yoni Wolf’s instructions “to better get a North Star underneath your tongue”––the hope for a better sense of direction.

But it’s the second of the original pair, “A Tale of Apes II,” that tells a story more in fitting with cLOUDDEAD’s origins. In it, a pair of guerilla artists in a basement apartment make absurd installation art: a sculpture of a bucket of blood, hand prints traced across the floor and covered in egg yolks and a black and white photograph of “Einstein growing frustrated over a sinkful of dirty dishes.” The imagined photograph recalls Doseone’s statement on the frustrations of living with collaborator-friends––even when you believe them to be geniuses––in the 2004 Wire profile: “It’s really hard to believe in your friend as this incredible artist that you share all this stuff with and then you’re cleaning his dishes.”

In For Hero: For Fool’s liner notes, Doseone writes of “A Tale of Apes II,” “This song is an ode to the touching and affecting time Why? and Adam had back in the Apartment A [in] Cincinnati [during] … cLOUDDEAD days, influencing and pushing one another to the lip of our potential.” The antithesis of the first ape track, the song is a tribute to the pleasure and occasional frustrations of art created in community rather than a solitary ego blasting from the stage; a testament to the fun and self-discovery of the time in which cLOUDDEAD shared apartments and created an enclave in which it was safe to get strange.

“The Hollows,” a new single from Why?, will be released on November 27 with their next full length, Alopecia, due out in March. Subtle’s new album, ExitingArm, is scheduled to arrive in May.

(Photos on pgs. 1 and 2 by Jessica Miller)

Related articles from The Fanzine:

Ross Simonini on Animal Collective

Los Angeles speed rapper Busdriver