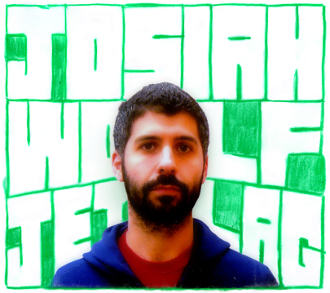

Josiah Wolf: Jet Lag (Anticon)

10.03.10

During the last five years, Josiah Wolf has been known primarily as the drummer for Why?, his brother Yoni Wolf’s band that signaled the Anticon label’s departure from hip-hop into more indie rock-based terrain. With the release of Jet Lag, Josiah is embarking on a new identity as a solo artist. Truly going it alone, Josiah played every instrument on his debut album. “I am actually doing the first tour myself,” Wolf said in a recent email exchange. Opening for Why? on the upcoming tour, Wolf will perform his songs solo “It will be a stripped down version (I don’t believe in backing tracks) so we will see how that goes.”

During the last five years, Josiah Wolf has been known primarily as the drummer for Why?, his brother Yoni Wolf’s band that signaled the Anticon label’s departure from hip-hop into more indie rock-based terrain. With the release of Jet Lag, Josiah is embarking on a new identity as a solo artist. Truly going it alone, Josiah played every instrument on his debut album. “I am actually doing the first tour myself,” Wolf said in a recent email exchange. Opening for Why? on the upcoming tour, Wolf will perform his songs solo “It will be a stripped down version (I don’t believe in backing tracks) so we will see how that goes.”

Adding to this new sense of independence, Wolf recently divorced after an 11-year relationship and relocated from California to Ohio, where he grew up, was taught drums by his rabbi father, and studied at the University of Cincinnati’s music conservatory. Much of the album was written in a cottage in the woods outside of Cincinnati. Jet Lag is a very personal account of the intricacies of his separation, communication, and change. Lyrically, some of the songs feel like diary entries, focused and sincere, with precise vocals: “And I couldn’t sell the bed/So I put it up for free/And this man he came to me/And then the house was clear”

The most successful moments on the album are the simple but emotionally-loaded lines that seem to come out of nowhere that make you feel like you’re right there with Josiah, wondering what is going on. The lyrics are not sad, or even very emotional, as one might expect from a breakup album. Instead, they capture the hopeless feeling of giving-up and being-given-up-on. My favorite line on the album is in the last part of the song “The New Car,” when he sings, “But when you told me I wasted your twenties I didn’t know what to say,” and then lets the line sit there for a few beats before going back into the chorus.

In the same song, Josiah sings: “You went and bought another car to help with the separation/But the night you got it home the black blood went all over the pavement/And I was waiting for the tow truck when it hit me how things are changing.” In order to relate to the lyrics, we have to imagine Josiah standing there, having this epiphany while standing in the street thinking about two seemingly disparate events (along with a strangely indistinct image of blood being spilled). As far as I can tell, this is how epiphanies actually happen. They come, almost unnaturally, out of inadvertently combining thoughts or reformulating a memory to redefine the way we are taking in an experience. And because this feels sincere and unforced, especially compared with the more clichéd, rhyming, break-up songs of mainstream, it is easy to picture ourselves having a similar experience.

Wolf was “inspired and influenced by [Why?] in many ways,” and it’s clear that they share a confessional nature and a strong interest in the everyday aspects of life. Josiah comes off as even more honest and direct than his brother Yoni, who has a definite hipster/ironic vibe that Josiah steers clear of. This same openness and sincerity, however, was something of an obstacle for him.

“Before I started much of the writing,” Josiah writes, “when I was learning cover songs, my ex-wife was the only one who knew of that for a while. I didn’t really keep my music writing a secret, though. People knew I was working stuff out. I didn’t play my songs for many people and some of the songs I didn’t play for anyone for a long, long time (until the recordings were almost finished). There is something about keeping a thing to yourself that makes it more powerful but I knew that eventually I wanted to share it. I am too reliant on others’ opinions and feedback to keep it hidden for too long. I always admire those artists who keep their work a secret their whole life, but perhaps that isn’t the healthiest way to live.” Appropriate to its lyrical content, the songs were recorded in similarly private and diaristic manner, but in the end one’s private creations become public.

Artists of all kinds seem increasingly dependent on the events of their own lives. They becoming accustomed to exposing themselves and being exposed to others — making realistic films with lifelike plots, writing books based directly on their mundane lives, writing songs about writing songs, and photographing their friends hanging out at parties. And consumers, increasingly, want to know whether or not they are consuming something “real”. Instead of adding to the poignancy and intimacy of the art, this kind of direct translation seems to simplify feelings and events into something immediately relatable, which makes things easier to understand and takes less mental energy to consume, but ultimately, for me, flattens the experience. In some cases, too, I almost see this full disclosure as a defense mechanism, a built-in argument against any potential criticism, artistic or formal, when the answer is always “Well, that’s what really happened.”

Artists of all kinds seem increasingly dependent on the events of their own lives. They becoming accustomed to exposing themselves and being exposed to others — making realistic films with lifelike plots, writing books based directly on their mundane lives, writing songs about writing songs, and photographing their friends hanging out at parties. And consumers, increasingly, want to know whether or not they are consuming something “real”. Instead of adding to the poignancy and intimacy of the art, this kind of direct translation seems to simplify feelings and events into something immediately relatable, which makes things easier to understand and takes less mental energy to consume, but ultimately, for me, flattens the experience. In some cases, too, I almost see this full disclosure as a defense mechanism, a built-in argument against any potential criticism, artistic or formal, when the answer is always “Well, that’s what really happened.”

While I admire the honesty, lyrical playfulness and inventive sonic juxtapositions of the album, I take issue with its marketing. Whether it was the decision of Josiah, Anticon or the publicists, the album is presented in press releases as a “divorce album” and, as often happens, the tone of the press release innevitably finds its way into reviews of the work including this one. That type of presentation of this or any work is in the end reductive. It’s obvious enough, in listening to the lyrics that a significant breakup has happened. But the content of the album is much deeper and more complex than that, and it was difficult to separate what I heard on the record from the information I had been presented with. Of course, songwriters have used material from their own lives as a source of inspiration throughout history, but it seems like a step backward to take it to another level and spell out what the songs are about beforehand.

Then again, it can be therapeutic to be explicit about one’s personal life. “Creating something is always a good way to get through difficult times,” Josiah writes. “I had lots of emotions through the whole experience. Emotion puts melodies and words into my mind. That is why Vivaldi only composed at night. He said he couldn’t get emotional in the morning.”

Josiah seems self-conscious about the extent of his information-giving, as in the song “Is The Body Hung” when he sings: “Am I giving you partly the wrong cue of what my life is?/ Am I giving you partly the wrong view of just how nice it is?”

“Anytime you put personal songs into the public it is a bit of a strange thing. Think about Elliott Smith or Daniel Johnston. Your entire view of them is based on their deepest emotions yet you know nothing about their daily selves. This is my first time doing this so I am a little unsure about it,” Wolf said, when I asked about the experience of publicizing his feelings. “My ex-wife likes [the album] a lot. That made me feel very good. I was afraid for her to hear it but when she did it was a definite part of the healing process for me. My family likes it. It makes my mom sad. My girlfriend likes it. It doesn’t bother me at all to have people I care about hearing it. If anything makes me nervous it is having strangers hearing it but obviously I’m willing to take that risk.”

________________________________________________________

Related Articles from The Fanzine: