The State of N.C. …Poetry (pt. 1)

25.07.08

Poetry haters and sympathizers alike can agree that poetry somewhat resembles avian influenza: to the former, it’s an aberrant plague to be avoided at any cost; while the latter notice it cropping up in the most unexpected places. My native North Carolina hasn’t exactly been regarded as a poetry hotspot since the heady days of Black Mountain College, and those days seem impossibly distant. I once gave a reading at the Black Mountain Museum in Asheville and discovered that all that remains of the place is a broken sign.

Poetry haters and sympathizers alike can agree that poetry somewhat resembles avian influenza: to the former, it’s an aberrant plague to be avoided at any cost; while the latter notice it cropping up in the most unexpected places. My native North Carolina hasn’t exactly been regarded as a poetry hotspot since the heady days of Black Mountain College, and those days seem impossibly distant. I once gave a reading at the Black Mountain Museum in Asheville and discovered that all that remains of the place is a broken sign.

I wouldn’t be so brash as to compare my own, modern NC poetry environment to those halcyon days. But there is unquestionably Something Up in North Carolina poetry. (Which is not to say nothing’s happened between the demise of Black Mountain and now, but at age 28, I’m still allowed to be historically myopic; I’ll pay for it in my 30’s.) Maybe it started with the first Carrboro Poetry Festival in 2005 (organized by Patrick Herron, who, at the time, was the poet laureate of Carrboro), which featured such out-of-town luminaries as Rod Smith, Linh Dinh, Christian Bök, and Lee Ann Brown alongside a host of local talent, and pretty much single-handedly put Carrboro on the poetry map.

But probably it started with the formation of the Lucifer Poetics Group (of which I’m a member) shortly prior, which brought together the diverse NC poets working under the ambiguous “post-avant” banner. Tastemaker Ron Silliman, who came to read for us as part of the currently dormant but once-formidable Desert City reading series (helmed by Lucifer Poetics founder Ken Rumble), blogged that we were “very possibly the liveliest poetry community not integrally a part of a major metro in the U.S.” There’s plenty of NC poetry beyond Lucipo––Andrea Selch’s Carolina Wren Press, for instance, has published Lucipo people and participated in Lucipo events, but predates and operates independently of Lucipo; its contribution to NC poetry cannot be overstated. Ditto for the Lucipo-affiliated but staunchly independent minor american reading series.

(I’m tiptoeing and qualifying so carefully because to attempt any definitive survey of a given poetry scene is to piss off a lot of people, since poets are understandably starved for attention and easy to accidentally slight. Here’s hoping that an up-front acknowledgement of my non-definitive, Lucipo-biased perspective will render my ellipses inoffensive. This isn’t really a state-of-NC-poetry article anyway; I’m just getting carried away with my set-up.)

It’s not like North Carolina is just spontaneously barfing up great poets: many if not most of the Lucipo poets came here from far-flung corners of the country, drawn into the ambit of the area’s universities (Duke and U.N.C., plus U.N.C.-Greensboro, N.C. State, et al.). It’s more of a right-place right-time thing, a fortuitous alignment of stars. Within a half-hour drive from my home in Durham, I’ve got Patrick Herron, Tony Tost, Ken Rumble, Chris Vitiello, Kate Pringle, David Need, Allyssa Wolf, Jon Leon, Joseph Donahue, and too many others to name here. If none of these names mean anything to you, then you’re probably one of the many, many Americans who don’t read modern sub-mainstream poetry. If you recognize them––hell, drop me a line, because I probably know you; it’s a small world.

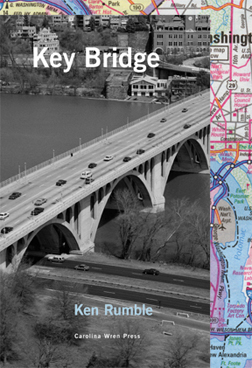

All of this set-up is just context for the real occasion of this article, a review of three killer books by three Lucipo peeps, all of which were released within the past twelve months and cumulatively made me just blush with NC-pride: Chris Vitiello’s Irresponsibility (Ahsahta Press), Tony Tost’s Complex Sleep (University of Iowa Press), and Ken Rumble’s Key Bridge (Carolina Wren). Note that I’m using the word “review” loosely: I’m stepping out from behind the veil of journalistic objectivity to extol the virtues of three good friends, whom I’m going to refer to by their first names, and about whom I’ve nothing but good things to say. I stand before you gloriously biased; my objectivity gleefully compromised. I’m assuming this will be okay with you, since I imagine you come to Fanzine for a respite from being sold things by allegedly disinterested parties.

All of this community-based, time-and-place stuff is relevant because, although their voices are very distinct, the books emanate from the same living community. They grew up together, from little bobbins sallied forth at readings and meetings to completed manuscripts. They cross-pollinated. These are books that know each other. Two of them are closely bound to worldly times and places, while one has more of an eternally echoing quality; all three of them revel in slippages of mimesis and syntax. And all of them use lapidary language and pyrotechnic erudition as dams to hold back a great flood of yearning and loss. It’s in Chris’s book that these qualities are writ largest, and it’s with Chris’s book we’ll begin.

In Irresponsibility (Chris’s second book, after Nouns Swarm a Verb), his voice is flat and uninflected; one might describe the way it picks itself apart as cagily neurotic. His meta-language opts for maximum transparency. Imagine language as a glass, and poetry, as mud splattered onto that glass in compelling or pleasing patterns. Chris wipes the glass clean to reveal all of its light-bending flaws and distorting curves. Through this glass, syntax tangles and untangles: “Tidal pools pock the beach/ Seagulls loiter as they evaporate/ That is vague and snowballs[.]” At first we see the scene: the pools on the beach, the loitering seagulls. We only notice the vagueness after Chris points it out to us. Are the seagulls themselves evaporating? What is “that?” Is “snowballs” a noun or verb? Chris lends new weight to the phrase, “You really had to be there,” as he undermines English usage until we no longer trust it to accurately describe experience.

Each poem in Irresponsibility is titled according to the date and location of its composition, but these are far from naturalistic idylls. The book’s opening lines—“Midmorning beachcombing/ This rock is four letterforms”—project its first thought into the interstice between the object known as “rock” and the word that signifies it, like the inevitable moment in a David Lynch film when the camera zooms into an object and emerges in an alternate reality. Chris worries this gap relentlessly, so that by the book’s end, signifier and signified seem to us to be connected only by gossamer strands of convention. Time and place are jumping-off points for Chris’s peculiar brand of intellection, which describes an eternal reconnaissance inward, or, in his words, “Not a vicious circle but a vicious spiral.” These poems chase their own splintering ramifications through the echo chamber of one quietly attentive mind, “toward the end of one’s ability to diagnose[.]” Each line takes us further from the physical scene at hand, deeper into the catacombs of language carved into the landscapes, up to the point where all fundamental terms have been so thoroughly destabilized that there’s simply nothing left to say. At moments like these, the book asks the reader to insert the actual objects it can’t quite pin down with words: “Glue a small piece of sandpaper in the white space below.”

Postmodern poets, steeped in poststructural theory, have long been obsessed with the gap between words and things. But Chris stands out from the crowd because of how meticulously and reverently he pursues this line of thought. This is not coy language play, with its deliberately evasive meanings and whiff of aloof superiority. This is the emulsion of a mind at war with itself, not veiling but tearing down veils, behind which: always more veils. And Chris is less interested in the chasm between a rock and “rock”‚—between things and nouns—than he is in the nested implications of conventional syntax and mimesis. In particular, the way he treats demonstrative pronouns would be classified by any sane administration as torture. A million tiny cuts flay them open and reveal them to be hollow, recursive, and much less stable than their ossification in everyday usage would imply: “Also this is four letterforms and this/ is a pronoun which represents/ this.” By the book’s conclusion, the word “this” seems the dead letter office of language, a place where messages disappear.

Irresponsibility is, in part, an attempt to use a language that is insufficiently sophisticated to describe the world to do just that: “The door is either open or closed and/ there are many degrees of being open.” In this, it is a heroic act, an urgent attempt to expand the continuum of degrees language collapses into vertices. But it is much more than that; seldom has a book so obsessed with the vicissitudes of language carried such emotional weight. It’s not just that Chris seems desperate to escape from the hermetic gyre of his mind, a bifurcated mind in search of a true center, although these moments—“Brent, I have to break out of this and/ not just to try something new”—are profound. (“Brent” refers to Chris’s friend, the Californian poet Brent Cunningham.) Chris watches and catalogs the increments of his life as carefully as the increments of his language, and his theoretical diary of slippage skews personal. “Doorways frame/ where inside touches outside/ Not itself a space or place but a planar edge,” and “Iris hesitates in doorways/ and has to be touched on the back of her head.” (Iris is Chris’s daughter, who, at another point in the book, “played with toy guns for the first time today.”)

It’s as if this unraveling of the sequences and durations implicit in language (“Duration masks condition/ Watch the whens”) is a deflected attempt at coming to grips with the sequences and durations of life itself. While it’s tempting to read the book as a complex metaphor for intellection, Chris says: “Each wave regressing affects/ the breaking of the next wave/ This is not metaphorical/ This/ is about waves/ This is easy.” He knows that the world is already a metaphor for itself, and the only deceptive statement here is “this is easy.” Nothing in Chris’s poems seems to come easy; it’s hard work to “establish the minimum and then have just more than it.” Irresponsibility encourages the reader to mistrust language; its paradox is that you come away from it trusting the author, who is not a deconstructive maze-maker, but a guide trying (and heroically, inevitably failing) to lead us out of the maze we enter the moment we try to communicate with each other, or try to make sense of our own lives with only the most rudimentary tools at our disposal.

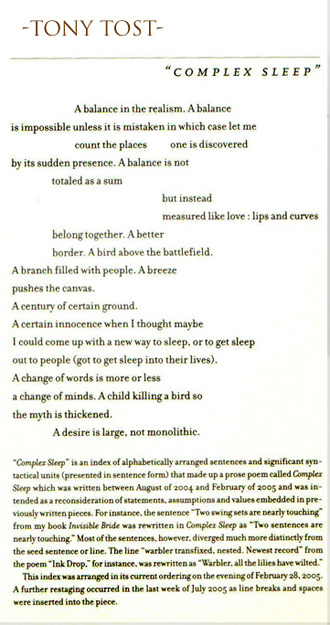

Tony Tost is the editor of Fascicle (to my mind, the best and most ambitious journal of poetics to hit the Internet in recent years) and the author, before writing Complex Sleep, of the Whitman Prize-winning book of prose poems, Invisible Bride. It was via the questing, Rimbaudian prose of Invisible Bride that I got to know and love Tony’s work, and it took a minute for me to get used to the mostly-lineated poems of Complex Sleep. The first few lines of the poem that opens the book, “Imaginary Synonyms” is a fair description of Tony’s transition from prose to verse: “Eventually we take it apart/ dissecting it palate by plate/ only to get smaller[.]” The oneiric weavings that comprised Invisible Bride are here intact, but they are more dispersed, more porously connected, and more fearless, unencumbered by the safety net of narrative logic. Tony’s verse is a marvel of extreme contrasts. We feel at once amid and above his psychic landscapes: “Up on Breeze : for what is isolation/ but Song in and not via Wind? We are still in the wind.” His lines have the grace of verse, but the weight of prose; a strange combination of lightness and heaviness, like anchors sailing easily through the air, or feathers clanging down like anvils. Careful enjambments slam home gossamer lines with unaccountable force: “[G]rief may be rotting half my brain/ but I remember all of your face/ faintly.” Tony’s voice manages simultaneously to boom like a god’s, and to tremble like a small, hurt bird’s.

Besides imbuing Tony’s poems with a massive breadth, these extreme contrasts suggest a sort of spiritual schism—language as a stitched seam attempting to reunify something cloven. Like Chris, Tony is interested in waves, which move in one direction only, and seems to lock oars against them, pushing backwards toward a point of origin even as he’s borne ever forwards: “Come home/ your father’s birthday is today[.]” “Squint” is the book’s second poem, a sequence of self-contained yet interconnected sentences, each quartered by comma-bound caesurae. Each is a sort of baroque aphorism unto itself, radiating a densely interior and subjective meaning: “But who has a parent, dark pools of blood, if a truth is uttered, there are no hours.” But taken together, a broader interconnectivity emerges. “Squint” begins with a creation myth—“Far from being, the music is already there, near the beginning, nearer everything.”—and ends with a kind of eschatological prayer. “The mercy of winds, the navel of an ape, the end of flesh, it was the mercy.” This sweeping scope is typical of Tony’s work, as is the sense of inestimable loss it entails—note the conflation of “the beginning” and “everything” and how far from both we’ve traveled.

“Imaginary Synonyms” and “Squint” are supplicated, prayerful poems, which kneel inside their own austere architecture. The tone superficially changes with “World Jelly” (previously published as a chapbook by Effing Press), which burns that austere architecture to the ground. According to the book’s notes, “World Jelly” was inspired by the poems of Chris Vitiello (“put this poem on your shoulder[,]” it commands, as befits a poem that is both Vitiello-redolent and engaged in an act of parroting), the lyrics of Robert Pollard and Bob Dylan, and Jack Kerouac’s haiku. It is a frothing mutant of a poem, blurring the line between aphorism and non-sequitur, replacing the first two poems’ quiet beatitudes with lewd innuendoes (“You will receive yours/ beneath the blanket”) and stentorian commands (“Asshole serpent/ write this down”). “Do not turn into me[,]” Tony warns, as if acknowledging the slippery slope of the poetic nihilism implicit in this “self-portrait with/ spiders in the grapes[.]” It appears to be a desecration of the lyric, but is actually a different, more belligerent kind of consecration: “Here I keep a record/ of what can be accepted/ what the lad has collected/ in the balance[.]”

This to me seems a crucial, exemplary moment in Complex Sleep, framing it as an elaborate scrapbook aiming to preserve “what the lad has collected” and to take a measure of the balance. The sequence titled “An Emperor’s Nostalgia” is dedicated to Tony’s wife, Leigh, and we can follow this preservationist thread through its declarations of fealty, so fierce that they come to seem like prayers against the past that bears us away and the future that bears down upon us: “This is the end of terror” and “We are not for the flies” and “You cannot lose to dying/ If your case is love.” And we follow it especially through the book’s long titular sequence, whose circuitous history—first, Tony rewrote or reconsidered various sentences and assertions from older work into a new prose poem, and then arranged the “significant syntactical units” of that prose poem into the alphabetically ordered index that appears here—makes for formal fireworks and a great spirit of play, as the index’s alphabetical arrangement shapes the propositions’ meanings and contexts. But I think the real power of the poem lies not with the fireworks, but the yawning existential sky that is their background; the great and nameless yearning from which the urge to preserve arises. Was it the narrator of Leonard Cohen’s Beautiful Losers who cried over his cut hair, consecrated his fingernail clippings? Isn’t a line of poetry just the same bodily emulsion, universal yet profoundly specific—and might not a worshipful man feel a pang of something like despair at the prospect of any of it slipping away? Might not one strive to make a record, a song suspended in, not swept away through, time’s windy passage?

The books of poetry I like best seem to illuminate a truth that attains universality by being exquisitely personal, where each line seems an instance of the author’s mind momentarily seeing itself clearly. Usually this comes through intuitively, although in this case, I can verify the hypothesis. Like his poems, Chris’s personal energy is quizzical and attentive. Tony’s is paradoxically strong and gentle, a bird’s heart in a bear’s sinew. And Ken Rumble’s is giddy and carnival-esque, implying fireworks, ringing bells, flashing lights, arcs of speed and force. Key Bridge, his debut book, follows suit. These poems are radiant sprays of typography: the lines slalom down the pages in serpentine ranks; unclosed brackets and parentheses hang like bursting rockets; dashes slash out staccato music; words splatter into painterly constellations of letterforms. But preceding all of this, the book opens with two concise lines that comprise an internal manifesto of sorts: “breath. )/ Now )[.]” The poems must be living things, and they must unfold in the eternally expanding moment of the present.

This call to presence might initially seem to be at odds with the book’s fixation on the past. The real Key Bridge spans the Potomac, and the book Key Bridge is a stuttering, elliptical survey of the texture, history, and strife of Ken’s native home of Washington D.C.. But this is not a museum-culture survey, history under dusty glass: Ken rips D.C. from its historical moorings and rejuvenates it with cinematic jump cuts; jags of overheard vernacular; montage-like splices of time, place, event, so the book becomes less about history than about a mind actively engaged with it, in a process that is living and ongoing. The dated entries comprise less of a temporal sequence than a series of rip-ups and start-agains, each a sortie against some chink in D.C.’s armor, trying to pierce its veiled heart. Ken courses through D.C.’s incandescence (“D.C. light crests on lampposts/ ripples through streets/ ripples through buildings/ through trees/ through cars/ through clothes/ ripples through you”), inhabits its sky (“way far from D.C. & way below, a river winds/ through a pancake middle”), plies its streams (“trips downstream with my parents & sister in/ from the suburbs through Rock Creek Park”), scales its architecture (“A low brick tower/ with turrets/ in the middle of the Northwest/ suburbs atop the hill end/ of Fort Reno Park”). A dream city sprouts like a dark garden, ever shifting, ever unsettled.

This call to presence might initially seem to be at odds with the book’s fixation on the past. The real Key Bridge spans the Potomac, and the book Key Bridge is a stuttering, elliptical survey of the texture, history, and strife of Ken’s native home of Washington D.C.. But this is not a museum-culture survey, history under dusty glass: Ken rips D.C. from its historical moorings and rejuvenates it with cinematic jump cuts; jags of overheard vernacular; montage-like splices of time, place, event, so the book becomes less about history than about a mind actively engaged with it, in a process that is living and ongoing. The dated entries comprise less of a temporal sequence than a series of rip-ups and start-agains, each a sortie against some chink in D.C.’s armor, trying to pierce its veiled heart. Ken courses through D.C.’s incandescence (“D.C. light crests on lampposts/ ripples through streets/ ripples through buildings/ through trees/ through cars/ through clothes/ ripples through you”), inhabits its sky (“way far from D.C. & way below, a river winds/ through a pancake middle”), plies its streams (“trips downstream with my parents & sister in/ from the suburbs through Rock Creek Park”), scales its architecture (“A low brick tower/ with turrets/ in the middle of the Northwest/ suburbs atop the hill end/ of Fort Reno Park”). A dream city sprouts like a dark garden, ever shifting, ever unsettled.

Like Barthelme’s Paraguay, this D.C. cannot be found on any maps. This D.C. only exists as a teeming chamber in Ken’s mind, for which his words are “an entrance, a door jamb/ from which to survey the room.” And so it is a jumble—quoted speech, geographical detail, Chamber of Commerce-caliber civic data collation, sense impressions, snippets of music, news items both pithy and mundane, the susurrus of streams and the “(whup, (whup, (whup” of helicopters blur into one stream-of-consciousness ramble through a dream D.C. parallel to the waking, collective one. Along the way, we meet a couple of Jennies, many bridges and rivers, crooks and cops, Lee Boyd Malvo (“shooting star”) and John Allen Muhammad, some herons and rooks, Tom Waits and John Wilkes Booth, Amos and Andy, Francis Scott Key, Artemis and Diana, Pierre L’Enfant and Muhammad Ali. All of these and more stride in Bunyanesque proportion to the mercurial landscapes they inhabit—whatever their actual relationship to the actual D.C., in Key Bridge, they become as sentinels, tirelessly treading the bounds of the city’s mythology. Their orbits give Ken’s D.C. its nebulous shape while simultaneously illuminating its conflicts.

When one takes an entire landscape and history inside of one’s self, one begins to feel responsible for it, and a lot of the book is taken up with Ken’s struggle with this dwarfing sense of responsibility—particularly for the various privileges and depredations of race. “Coming up, if I’d said the ‘N-word’/ my parents/—liberal, kind, pale/ as book pages, freckly, Catholic,/ love Cézanne—/ would’ve made me pray.” Ken goes on to overhear racial slurs in Georgetown and Cleveland Park, rolls through the dangerous parts of town, talks jive with other honkies, teases the seam between black majority and white fright, and contemplates how the “City Beautiful, City of White” can “hold so much time.” The cumulative result is less of an attempt to explain than simply to perceive, to document, and to palpate: the history of D.C. as an ineffable radiance, refracted through the prism of Ken’s busy mind. If Key Bridge is a map, it is a purely cognitive one, a grid of latitudes and longitudes coordinated along the axes of events and perceptions. Events transpire during the book’s composition, like the previously mentioned sniper attacks, and quickly sink beneath its bubbling surface. An entry dated “15.september.2001” reads, “I know nothing/ even about my city/ my wounded angel/ my paramour my geometry/ I’ve been so long for you/ Where am I? Where am I now?/ trying to clasp the whole/ (all of you, all of us)/ to love the broken enough[.]” There is no reconciliation, only yearning, curiosity, and the boundless love that informs Ken’s personality. If it is, at times, a love letter to the city, it is also a eulogy for the place of Ken’s origin, which, the book implies, he left without ever truly understanding. The longing that animates it is a longing to understand, and also to preserve: when a story ends without any solid conclusion, perhaps our only recourse is, to quote one entry in its entirety, to “write what’s gone.”

When one takes an entire landscape and history inside of one’s self, one begins to feel responsible for it, and a lot of the book is taken up with Ken’s struggle with this dwarfing sense of responsibility—particularly for the various privileges and depredations of race. “Coming up, if I’d said the ‘N-word’/ my parents/—liberal, kind, pale/ as book pages, freckly, Catholic,/ love Cézanne—/ would’ve made me pray.” Ken goes on to overhear racial slurs in Georgetown and Cleveland Park, rolls through the dangerous parts of town, talks jive with other honkies, teases the seam between black majority and white fright, and contemplates how the “City Beautiful, City of White” can “hold so much time.” The cumulative result is less of an attempt to explain than simply to perceive, to document, and to palpate: the history of D.C. as an ineffable radiance, refracted through the prism of Ken’s busy mind. If Key Bridge is a map, it is a purely cognitive one, a grid of latitudes and longitudes coordinated along the axes of events and perceptions. Events transpire during the book’s composition, like the previously mentioned sniper attacks, and quickly sink beneath its bubbling surface. An entry dated “15.september.2001” reads, “I know nothing/ even about my city/ my wounded angel/ my paramour my geometry/ I’ve been so long for you/ Where am I? Where am I now?/ trying to clasp the whole/ (all of you, all of us)/ to love the broken enough[.]” There is no reconciliation, only yearning, curiosity, and the boundless love that informs Ken’s personality. If it is, at times, a love letter to the city, it is also a eulogy for the place of Ken’s origin, which, the book implies, he left without ever truly understanding. The longing that animates it is a longing to understand, and also to preserve: when a story ends without any solid conclusion, perhaps our only recourse is, to quote one entry in its entirety, to “write what’s gone.”