Roid Rave: Steroids, They Do A Body Good?

05.03.09

In 1995, when Bob Clapp entered the supermax federal prison in Florence, Colorado, he possessed the body of an athletic 30-year-old. With striated quads, robust biceps, and six-pack abs, he was in peak physical shape. Just 24 months later, the Arizona native left the Alcatraz of the Rockies a shell of his former self. Forty pounds lighter, four inches wider in the waistline, and with 14 percent more body fat, Clapp reentered society a flabby, withered old man. There was no hunger strike, no physical illness or abuse by guards, no crippling depression that left him sedentary while doing his time. In fact, Clapp had spent nearly every waking hour of his incarceration lifting weights and exercising; he paid close, meticulous attention to his diet, and even had friends from the outside regularly ply him with vitamin and mineral supplements. Clapp’s physical decline, as it happens, was simply a matter of returning to normal—normal, that is, for a 61-year-old man.

In 1995, when Bob Clapp entered the supermax federal prison in Florence, Colorado, he possessed the body of an athletic 30-year-old. With striated quads, robust biceps, and six-pack abs, he was in peak physical shape. Just 24 months later, the Arizona native left the Alcatraz of the Rockies a shell of his former self. Forty pounds lighter, four inches wider in the waistline, and with 14 percent more body fat, Clapp reentered society a flabby, withered old man. There was no hunger strike, no physical illness or abuse by guards, no crippling depression that left him sedentary while doing his time. In fact, Clapp had spent nearly every waking hour of his incarceration lifting weights and exercising; he paid close, meticulous attention to his diet, and even had friends from the outside regularly ply him with vitamin and mineral supplements. Clapp’s physical decline, as it happens, was simply a matter of returning to normal—normal, that is, for a 61-year-old man.

You see, Mr. Clapp was incarcerated for the federal crimes of smuggling, dealing, and illegally possessing anabolic steroids. As a byproduct of his jail time, he had to do without the synthetic testosterones that were helping to reverse the negative effects of aging.

“I can’t see why someone would want to cave into the idea of, ‘We get old and we should just accept it and age gracefully,’” says the now–72-year-old Clapp, who, excepting his time in prison, has been taking anabolic steroids for 50 years. Since his release, he’s been obtaining his steroids legally, via a prescription from an anti-aging physician, and claims to maintain the biological age of a 36-year-old. Without his “tools,” as he calls them, Clapp says he would run the risk of osteoarthritis, cardiovascular issues, muscle wasting, depression, fatigue, a lessened mental capacity, and zero sex drive—in other words, Mr. Clapp contends he would suffer the ravages of being old.

“If you can take something that allows you to continue to wake up and smell the roses,” says Clapp, a retired educator and self-described philosopher about human existence, “why wouldn’t you?”

To buttress his argument, he offers his own body as evidence: At just over six-feet-one, the septuagenarian weighs 190 pounds and has a 32-inch waist and 11 percent body fat.

What’s lost in the noise of the steroids debate is the example of Bob Clapp, who, after a half century of steroid use, has ostensibly suffered no irreparable negative side effects. Some would argue that Clapp is an outlier, the exception that proves the rule. But to do so would be to misunderstand how steroids work.

For the unversed, a primer: Testosterone is an anabolic steroid primarily secreted by the testicles. It’s the principal male sex hormone and plays a key role in general health and well-being. Specifically, it helps the body maintain sex drive, sperm production, mental and physical energy levels, bone density, and, yes, muscle mass and strength.

For the unversed, a primer: Testosterone is an anabolic steroid primarily secreted by the testicles. It’s the principal male sex hormone and plays a key role in general health and well-being. Specifically, it helps the body maintain sex drive, sperm production, mental and physical energy levels, bone density, and, yes, muscle mass and strength.

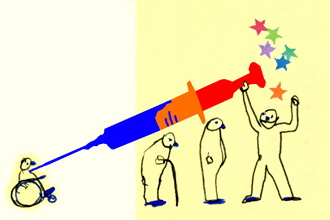

Generally, after the age of 30, a man’s testosterone levels begin to decline, and with them, all of the aforementioned benefits. Hence, the reason a 40-year-old sags and bloats, and loses the definition of his muscles, is due to a lower level of testosterone. If he takes anabolic steroids exogenously, that is, originating from outside the body, his testosterone level will increase. Thus, a 40-, 50-, or even 60-year-old man can dial back the clock to the hearty physiology of a 30-year-old. Some might argue that, taken out of the context of professional sports, using steroids is akin to taking a pill to combat high cholesterol or high blood pressure—you’re merely refusing to give in to old age.

Where people get into trouble is when they surpass an optimal physiologic range of testosterone—which can easily be established with a blood test—and move into the superphysiologic. Think the difference between the svelte and powerful body of Ben Johnson, the disgraced Canadian track star of the 1988 Olympics, and the overgrown physique of Hulk Hogan.

“It’s a drug like any other,” says Clapp. “There’s use, and then there’s overuse. It’s like if you get a prescription from your doctor that says take X. Well, the people who get into trouble take X + X + X; it’s the fool’s logic of more chocolate ice cream must be better.”

Of the negative effects that can result from overuse, there’s acne, high blood pressure, lower sperm count, and the potential for gynecomastia, known in the gym as “bitch tits”—none of them fatal, and none of them irreversible. But what we hear in the public outcry against steroids is much more alarming: There’s the nightmare story of Chris Benoit, whose so-called “roid rage” led the pro wrestler to murder his wife and son before committing suicide; the fatal heart attack at age 40 of one-time Major League Baseball MVP Ken Caminiti; the teenage suicide of high school athlete Taylor Hooton; and the deadly brain tumor of NFL legend Lyle Alzado. To be sure, all tragedies in their own right, but there’s no medical evidence linking any of these deaths to anabolic steroid use.

If you scratch beneath the surface of the sensational headlines, what’s plain is the absence of the authoritative voice of a doctor. That’s probably because the voice of reason from the medical community often turns up on the unpopular side of the issue. Take Norm Fost, M.D., who served on President Clinton’s Health Care Task Force and is currently director of the bioethics program at the University of Wisconsin. At a Bob Costas–moderated debate on performance-enhancing drugs in sport held last year in New York, by a forum called Intelligence Squared U.S., Fost had this to say: “Lyle Alzado died of a brain tumor. Then the New York Times and Sports Illustrated told us that this was due to steroids, without a single quote from an informed physician or a single source showing any association with steroids … because there is none!”

“It’s all anecdotal,” says Mauro DiPasquale, M.D., a widely renowned expert on ergogenic aids, of the so-called evidence linking steroids to various health issues. “The studies that blame steroids for certain heart problems, for sudden death, etc., are not the kinds of things that make up evidence-based medicine. In other words, they don’t really mean all that much. Bottom line: the adverse effects of steroids have been wildly overstated.”

When it comes to the non-medical use of steroids, the fact of the matter is that conclusive long-term studies have yet to be done. Because of the stigma attached to steroids, many researchers and doctors would rather not get near the subject. And while Dr. DiPasquale won’t say that steroids are innocuous, he does allow that, under the right conditions, he’d give the green light to a healthy adult male wanting to use them.

“If it was legal, and no one had any moral or ethical objection,” he offers, “I’d say ‘Go for it.’ Why not? They’re drugs. They can be misused, but they can be used properly, too. Let’s face it, if all the objections were removed, there would be very little difference between prescribing steroids to an adult male and prescribing birth control pills to a woman. What an anabolic steroid user has to do is weigh the possibility of an increased risk of prostate cancer—which we don’t know yet—against the fact that they look and feel great, have a decrease in depression, an increase in sexual activity, and decrease in fatigue. It will give you better quality of life, there’s no doubt about it.”

Over the past century, the medical community has made great strides in technology and pharmaceuticals that have directly resulted in people enjoying longer and better quality of life than their ancestors. So one might ask, why draw the line at anabolic steroids? If it’s good for treating muscle wasting in those suffering from cancer and AIDS, then why not for augmenting the general health and well-being of the average Joe?

The resistance goes all the way up to the congressional level. In 1990, the U.S. Congress passed the Anabolic Steroid Control Act, which classified these substances as Schedule III drugs, making them illegal to possess without a legitimate medical reason and a prescription from a licensed physician—despite the fact that expert witnesses from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the Federal Drug Administration (FDA), and the American Medical Association (AMA) all testified and were unanimously opposed to any such criminalization.

The events that led up to congressional action might help explain the reasoning behind it. In 1988, just two years prior to Congress taking up the issue, steroids became front-page news when aforementioned track star Ben Johnson was stripped of his Olympic gold medal over the revelation that he’d enhanced his performance with anabolic steroids. Although the original clamor was about maintaining a level playing field in professional sports, the policy and media debates that led to criminalization focused not only on cheating elite-level athletes, but on the at-risk youth who look up to them. Any rational debate on the subject was quickly muffled by the emotional outcry, “Think of the children!”

The problem with such politicization of the issue, says Harvard-trained endocrinologist Michael Scally, M.D., is that “anabolic steroids are not looked upon as a class of drug used for medicine, they just look like a class of drug in which criminal activity surrounds. So physicians don’t get near the subject or near the use of them for fear of reprisal by the medical board, and the law.”

The problem with such politicization of the issue, says Harvard-trained endocrinologist Michael Scally, M.D., is that “anabolic steroids are not looked upon as a class of drug used for medicine, they just look like a class of drug in which criminal activity surrounds. So physicians don’t get near the subject or near the use of them for fear of reprisal by the medical board, and the law.”

Dr. Scally should know. In 2005, the Texas Board of Medical Examiners took his medical license away, for prescribing anabolic steroids for non-medical reasons. Scally denies ever having advocated the non-medical use of steroids, much less ever acting as a “drug dealer.” Instead, the doctor maintains he was treating lapsed steroid abusers who were left with a resulting condition known as hypogonadism, wherein the testicles cease to produce testosterone on their own.

As Dr. Scally tells it, as a result of coming in 2nd place in a Mr. Texas competition in 1994, at the age of 42, he was brought into contact with people in the gym who were having trouble coming off of steroids, who ended up being hypogonadal. After hearing one too many stories involving these past users seeking the help of a physician, only to be told, “Get out of my office, I don’t want anything to do with you,” Dr. Scally went about studying the literature to see what he could do. “These guys were looking for help,” he says, “and they were treated as pariahs.”

Scally’s basis from the very beginning was for treatment only once a person had discontinued anabolic steroid use. Ironically, however, the treatment he prescribed involved legitimate administration of steroids. The medical board wasn’t buying it.

“One of the board’s so-called experts in my case said that even just taking care of the side effects of anabolic steroids, you should have your license taken away,” marvels Scally.

To his mind, the hysteria and politicization surrounding steroids have caused the medical and research communities to regard the issue of its prescription and use not as a medical problem, but as a legal problem. “Hence, heroine users who come to a doctor’s office are not treated as badly as some of the people who use anabolic steroids,” he says. “From what I hear from these people, they were literally treated like they were felons. I don’t understand that.”

Robert Tan, M.D., founder and director of the Houston-based OPAL Medical Clinic, which focuses on men’s health, has one explanation: “Public policy and public opinion have been based on people who use steroids in larger amounts,” he says. Tan, whose practice has been incorporating hormone replacement therapy for 15 years, says that in Texas, “every prescription is tracked by the DEA, so a lot of physicians are not comfortable. If I write a lot of steroids prescriptions, very soon they’ll be knocking down my door and looking at my records.”

Most of the people who come to see Tan, he says, “are very symptomatic and … really need help, and they’ve often been turned away by other doctors.”

Luckily for Donnie Parks, a 49-year-old man from the Houston area with no past connection to steroids, who began suffering four years ago from extreme testosterone deficiency, Tan was the first physician he went to for help. After having enjoyed a lean, 5-foot-9-inch-tall frame for the entirety of his adult life, Parks had gone from a fit 155 pounds to a grossly out-of-shape 225, all in over the course of just one year. There was no discernible reason for such a dramatic transformation—Parks’s diet and physical routine was the same as it had always been.

“Aside from the weight gain,” says Parks, “I suffered depression, decreased libido, an inability to get or maintain an erection, swelling of my breasts, and extreme tenderness of my nipples.”

With the help of a blood test, Tan diagnosed him as having the testosterone level of a 90-year-old man. After exhausting all natural methods of kickstarting Parks’s own testosterone production, Tan resorted to the exogenous introduction of anabolic steroids. To this day, Parks has been on a compound formula of testosterone and cypionate (a concoction not foreign to the body-building community).

“I started to feel better within a week to ten days,” says Parks. “Aside from the weight loss and increase in muscle strength, the depression’s gone, I have energy, I think more clearly, I’m virile again.”

Cognizant of the public’s tendency to view this type of drug use within the context of the gym, he adds, “My motive wasn’t about being Mr. Universe; it was about getting back to normal, about being a normal, functioning male [again].”

But some medical ethicists do not accept Parks as someone with a legitimate medical condition. Andropause—or, male menopause—remains a controversial topic in the mainstream medical community. As Peter Conrad, a Brandeis professor of medical sociology and author of the book The Medicalization of Society, contends, “After it was synthesized, testosterone became a drug in search of a disease to treat, by both the endocrinologists and by pharmaceutical companies. It clearly became a vehicle by which doctors and drug companies medicalized male aging. Subsequently, men sought it out as an anti-aging elixir.”

The underlying message is that Parks’s symptoms are nothing more than the natural byproduct of getting older, and that to characterize them as a medical condition in need of treatment is not only unnecessary, but, perhaps, unethical.

“I’ve heard this before,” says Tan. “This attitude of ‘Why do you want an advantage? Why can’t you just accept the fact that you’re dying? Why can’t you just behave yourself and be your age?’ There are academics out there who have this philosophy … all of them don’t see patients. When I see people walking through my door who need help, not helping them would be against my creed.”

Parks’s reaction to the medicalization argument is similarly subjective: “The people who say that aren’t the ones who are suffering,” he says, adding that, “Look, I see nothing ethically wrong with wanting to live a fuller life and every aspect that that fuller life encompasses. I’m truly grateful that there was someone out there who knew what was going on with me, and that there was a medicine that could treat it. And I can equate that to a diabetic who’s grateful that there’s insulin.”

Steve Mead, a 52-year-old restauranteur from Phoenix, Arizona, is equally as impassioned as Parks on the matter. At 45 years old, standing six-feet-one, Mead weighed 315 pounds—“all in my stomach,” he says. He suffered many of the same symptoms as Parks did, in addition to severe sleep apnea. After a doctor tested his hormone levels and documented them as being medically deficient, Mead was prescribed testosterone. Within four months, he lost 68 pounds, as well as all the lethargy that went with it. (Today, he weighs 245 pounds, with a mere 7 percent body fat.) Asked what other benefits he enjoys as a result of the treatment, Mead hesitates for a moment, seemingly a little choked up at the robust state of his health.

“Just overall well being,” he says. “It’s hard to explain, but it’s easy to live. It takes all the side effects of getting old, and puts them back to in your mid 20s.”

Had he never had hormone replacement therapy, Mead believes he would deteriorate. “Personally, I think I’d just go in the hole,” he says. “My energy level would go down, my libido would go down, I’d start losing muscle. And then you don’t feel good about yourself so you just start overall depression.” Mead acknowledges these symptoms would, for so many other men, be considered just a state of normal progression. But it’s his right if he wants, he argues, to “fight nature.”

“I don’t want to age as fast as other people,” he says. “I want to be around when my boys have their kids. And that’s my personal choice.”

Mark L. Gordon, M.D., the medical director of Millennium Health, a group specializing in interventional endocrinology, has a more medicine-based rebuttal against the medicalization argument. In his experience, an untreated testosterone deficiency is what oftentimes leads to more medicalization. Take the case of “James,” a patient of his. “He had ADD,” Gordon says, “so he was put on Ritalin. Ritalin causes blood pressure to go up, so he’s put on blood pressure medication. The blood pressure medication causes him to be irritable and he gets depressed, so they put him on anti-depressants. We found out that he had a testosterone deficiency, so we put him on an ultralow dose of testosterone. His symptoms disappeared and he got off all three medications. His ADD disappeared, so he was taken off Ritalin. Without the Ritalin, his high blood pressure disappeared. Since the Ritalin and the blood pressure medication weren’t causing the irritability and the depression, he didn’t need his antidepressants anymore.”

Gordon fears that the current trends in drug policy are only becoming more restrictive. He cites the Human Growth Hormone Restriction Act of 2007 as an example. “It’s congressionally dictated,” he says, exasperated. “You can only prescribe it for six medically defined illnesses. The physician’s acumen, the physician’s training, the physician’s experience is what should guide them in what they can/should be able to use. We shouldn’t have federal interdiction telling us what drugs we should use, and how we should use them.”

“Bodily sovereignty,” says Clapp, placing an ideology to the choice by patients to use these drugs without government intervention. “It’s the notion that your body belongs to you and no one else. And as soon as they step in and say they will take charge of your body in any manner, that’s the first stage of slavery.”

Clapp’s Roe v. Wade-like argument may be compelling, but what’s more likely to change public opinion and policy regarding anabolic steroids is the fact that these drugs are the bedrock of a burgeoning anti-aging industry, where those nearing 40 and beyond can go to a clinic and take effective and controlled steps that will aid them in reversing the aging process. Science, in the long run, will win out.

At least that’s what Clapp, who takes a Darwinian view of the matter, believes.

“If you have the intellectual capacity to move against [when you’re going to die,]” he says, “you’re going to move against it.

“There’s many more important things here than how a man gets a bigger bicep or hits a ball farther,” adds Clapp. “The survival of the human race can be based in this thing we’re talking about.”

Jordan Heller is a writer living in Brooklyn. He can be contacted at jordhell@gmail.com.