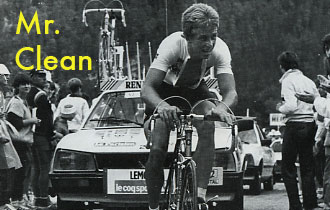

MR. CLEAN: Greg LeMond and Pro Cycling’s Doping Problem

07.07.07

During his thirteen years as a professional cyclist, Greg LeMond never used performance-enhancing drugs or artificial hormones or transfused blood, nor was he ever accused of doing so, and yet in a sense his legend has become the greatest casualty of doping’s encroachment into the sport. LeMond—who retired in 1994 and who has to be bored selling frames with his name on the down tube—is acutely conscious of his withering legacy. He knows that his “clean” achievements, which once appeared superhuman, now look mortal.

During his thirteen years as a professional cyclist, Greg LeMond never used performance-enhancing drugs or artificial hormones or transfused blood, nor was he ever accused of doing so, and yet in a sense his legend has become the greatest casualty of doping’s encroachment into the sport. LeMond—who retired in 1994 and who has to be bored selling frames with his name on the down tube—is acutely conscious of his withering legacy. He knows that his “clean” achievements, which once appeared superhuman, now look mortal.

And perhaps as a consequence, LeMond has established himself as the go-to whistleblower whenever a new doping scandal crops up. He is perfect for the job, admittedly. When he rode in the peloton, he often behaved like cycling’s spoilsport, pointing out the cheaters and the dopers to racing authorities and the velo press—who, to his frustration, were generally unsympathetic.

So when American racer Floyd Landis tested positive last July for spiked testosterone levels just four days after winning the Tour de France, it was entirely predictable that LeMond would emerge from the woodwork and give television interviews encouraging the accused to come clean for the good of the sport. What was somewhat less predictable, though, was LeMond’s testimony on behalf of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency at Landis’s arbitration hearing several weeks ago.

The purpose of LeMond’s May 17 appearance, everyone assumed, was to reiterate his insider opinions about cycling’s doping problem—even if they were hardly news to anyone who follows the sport. But instead, under oath, LeMond stated the following: That in order to prevent his appearance, Landis’s manager had called him the day before and threatened to reveal that an uncle molested LeMond when he was six years old. (For an excellent account of the hearing and how blackmail entered the picture, see VeloNews. LeMond explained that he had confided this information to Landis last August by telephone. He had wanted to persuade Landis that keeping a dark secret would inevitably eat away at him. “This will come back to haunt you when you are 40 or 50 . . . this will destroy you,” he said, recounting their conversation. LeMond, now 45, must have known what he was talking about. This was the first time he had publicly spoken about his sexual abuse.

It is of course understandable why, prior to Landis’s hearing, LeMond had not been forthcoming about his molestation. And yet his decision to break his silence now is striking for how closely it fits the tragic profile he has always cut.

It is of course understandable why, prior to Landis’s hearing, LeMond had not been forthcoming about his molestation. And yet his decision to break his silence now is striking for how closely it fits the tragic profile he has always cut.

LeMond was the first American man ever, in 1986, to win the Tour de France, cycling’s premier stage race (Marianne Martin of Fenton, MI won the inaugural women’s course in 1984—talk about forgotten). But LeMond’s career was stymied by repeated misfortunes, and he lost two years at his physical peak to a nearly fatal hunting accident. That he subsequently launched a one-for-the-ages comeback has only deepened the ironies. For LeMond’s story, in his own country at least, has been overshadowed uncannily by Lance Armstrong’s.

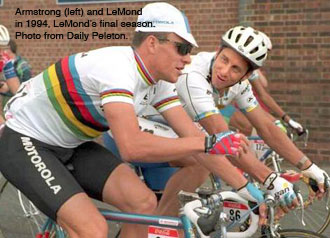

In contrast to LeMond, Armstrong, who retired two years ago, has consistently been on the receiving end of doping accusations, although last year he was cleared of any remaining official charges. As you might guess, among those who have been skeptical of Armstrong’s denials is LeMond. In July 2004, at a time when Sheryl Crow’s then-squeeze was collecting the fifth of his record-shattering seven consecutive Tours, LeMond told a French daily, “I don’t know how he can continue to convince everybody of his innocence.”

The reality is that Armstrong didn’t need to. The prevailing attitude about doping in pro cycling circles—the view shared by the athletes, the coaches, the organizers and sponsors, the doctors, and the lawyers—can be most succinctly described as don’t ask, don’t tell. Or, to paraphrase the unreflective contentment of one Crow anthem, if doping makes you go faster, it can’t be that bad. Having prevailed in the Tour himself a mere three times, LeMond’s remarks about Armstrong were easy to dismiss as sour grapes, a perception he reinforced by later retracting his comments.

Still, there is more to his role as cycling’s self-appointed watchdog than rank bitterness. LeMond’s most admirable trait as an athlete was his sense of probity, even if he could be irritating about it. This is a man after all who risked a private confession in the naïve hope that Landis might be inspired to rescue the sanctity of his beloved cyclisme (according to LeMond, Landis responded, “What good would it do?”) By insinuating himself into the Landis scandal, LeMond has reminded us that as recently as twenty years ago it was possible to become a cycling titan on the strength of one’s own two legs.

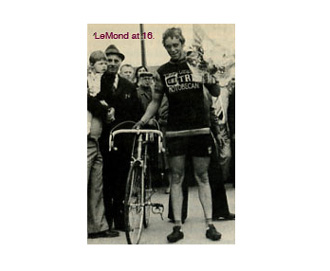

Greg LeMond was born in 1961 in Lakewood, California, an archetypal mid-century Los Angeles suburb originally settled by aerospace workers and their families. The San Gabriel River divides Lakewood from Cerritos, the town where I was raised, and amateur cyclists use its paved banks to pedal south to the Pacific or north to the mountains.

Greg LeMond was born in 1961 in Lakewood, California, an archetypal mid-century Los Angeles suburb originally settled by aerospace workers and their families. The San Gabriel River divides Lakewood from Cerritos, the town where I was raised, and amateur cyclists use its paved banks to pedal south to the Pacific or north to the mountains.

The future wunderkind didn’t start biking, however, until after his father transplanted the brood to Nevada. There, Bob LeMond made a comfortable living in real estate, affording him the leisure time to share his zeal for outdoor sports with his son. It was 1974 and freestyle skiing—which involves tricks and aerial maneuvers—was Greg’s first love. Cycling was just a means of off-season conditioning. But his instant aptitude—especially for mountain climbing, the most physically demanding aspect of road racing—was undeniable, and as a teenager he was already considered his sport’s rising prodigy. The gold medal at the Moscow Olympics would have been his for the taking, and when the Carter administration initiated its boycott, the logical next step for LeMond was to go pro. That said, for an American cyclist to be signed by a European team in 1980 was simply unheard of.

He didn’t go with just any team either; he joined Renault-Elf-Gitane, coached by the revered directeur sportif Cyrille Guimard. Although he was expected to develop his talent and win selected smaller races, LeMond was hired as a domestique, the traditional role for a talented apprentice, as well as the older and less gifted riders on the team. As their servile title implies, the domestiques are expected to do as they are told.

If this sounds like the plot of a Henry James novel (“the American with that boyish demeanor” declared one CBS Sports announcer), LeMond was ideally cast as the Yankee ingénue: He would let the sophisticates mock him, but only for so long. Within two years, during which he studied the sport’s archaic customs and learned French, useful for understanding not only his teammates and the press but the rivals trash talking him in a breakaway, LeMond became the first American to win the annual World Championship road race. His victory was especially impressive because, as in the Olympics, athletes compete as members of a national team, putting him at a distinct disadvantage. A year later, in 1984, he finished third in his first Tour de France, earning the coveted white jersey awarded to the top neophyte rider. (The overall champion wears a canary yellow jersey, le Maillot Jaune).

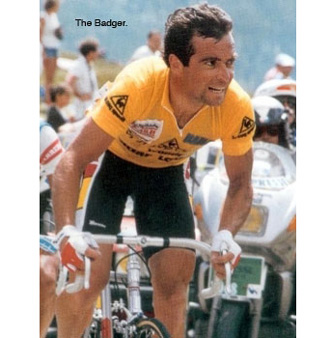

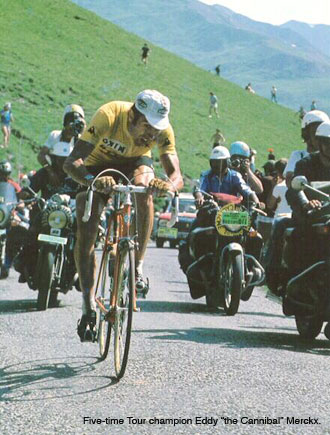

At age 23, LeMond was the heir apparent to Bernard Hinault, the handsome, feisty Breton known to the rest of the peloton as the Le Blaireau, or the Badger. By that time, Hinault had accumulated a whopping four Tour victories. He planned to retire in two years, on his 36th birthday, but before that he had his sights set on a fifth Tour, which would put him in a tie for the then all-time record with Jacques Anquetil (1957, 1961-4) and Eddy “the Cannibal” Merckx (1969-72, and 1974). Hinault persuaded LeMond to abandon Renault and join him as the co-leader of his La Vie Claire squad, promising that the team would be his to rule in two years. The ultimate effect of this new partnership, though, was to set the stage for the first tragedy of LeMond’s career.

Cycling fans—and French fans in particular—require panache from their champions; it is not enough for one to win, it must be done in style. It had long been Hinault’s habit, when in possession of the yellow jersey, to ride at the front of the peloton and set the day’s pace, his teeth bared. Typically, this is considered a poor strategy for defending the Maillot Jaune, but in Hinault’s case it was an expression of panache—a flamboyant challenge to his opponents.

Cycling fans—and French fans in particular—require panache from their champions; it is not enough for one to win, it must be done in style. It had long been Hinault’s habit, when in possession of the yellow jersey, to ride at the front of the peloton and set the day’s pace, his teeth bared. Typically, this is considered a poor strategy for defending the Maillot Jaune, but in Hinault’s case it was an expression of panache—a flamboyant challenge to his opponents.

However, on the afternoon of the ascent to Luz Ardiden in the Alps, the 1985 Tour de France’s most grueling stage, the Badger was recovering from the shock of a nasty fall he had incurred the day before. It was all Hinault could do to stay with the main pack when Irishman Stephen Roche, who was 6:14 behind, broke away. LeMond, who was in second place in the standings, 3:38 behind, followed Roche.

Ostensibly, LeMond was counterattacking. It is the responsibility of a senior domestique not to let a rival forge ahead unchaperoned. But the truth, plain to see on television, was that LeMond was eager to drop his breakaway companion and take the stage—and with it the Tour—for himself. Soon (this was all still on camera) the La Vie Claire team car pulled alongside them. Hanging from the driver’s window, Paul Koechli, La Vie Claire’s directeur sportif, pleaded with LeMond to slow down and protect the Badger’s vanishing lead. Following a heated argument en français, LeMond at last eased up on the pedals. At the finish line, he could not conceal his tears.

Out of duty, LeMond had deliberately thrown the 1985 Tour de France.

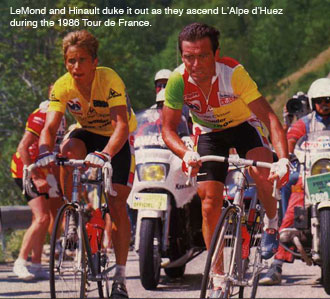

To thank him for this sacrifice, Hinault declared on the winner’s stage that he would ride for LeMond’s benefit in 1986. “But as the Tour approached, his tune changed,” LeMond later said. “First, he said that he would work for me only if I was clearly stronger than him. Then, at a press conference on the eve of the opening stage, he said the leader of our La Vie Claire team would be the one who was the strongest when we began the key stages in the mountains.” Until the final days of the race, Hinault maintained these mindfucks and rode to win.

To thank him for this sacrifice, Hinault declared on the winner’s stage that he would ride for LeMond’s benefit in 1986. “But as the Tour approached, his tune changed,” LeMond later said. “First, he said that he would work for me only if I was clearly stronger than him. Then, at a press conference on the eve of the opening stage, he said the leader of our La Vie Claire team would be the one who was the strongest when we began the key stages in the mountains.” Until the final days of the race, Hinault maintained these mindfucks and rode to win.

It didn’t matter. LeMond was unquestionably the peloton’s strongest rider that July, and he finished not only with the Maillot Jaune but with the garish jack-of-all trades “combination jersey,” for his prowess in every facet of the race—climbing, individual time trials, sprinting. Showing uncommon good grace after his victory, LeMond even settled for second place a couple of weeks later at the Coors Classic–the sole America stage race that drew Europeans and an event which he had previously owned—so that the Badger could end his career with a swan song.

The summer of 1986 should have been the beginning of cycling’s greatest legend. But instead of winning a second Tour in 1987, LeMond was fortunate to be alive. That April, while turkey hunting in Northern California, he was accidentally shot by his brother-in-law. Approximately 40 shotgun pellets struck him, some 37 of which doctors ultimately left embedded because they had landed in vital organs and were not safely removable. LeMond frequently underwent surgery over the next two years, including procedures for appendicitis and tendonitis.

Did anyone other than LeMond himself believe that he could make a viable comeback? Cycling’s ruling class certainly didn’t. They had always respected l’américain but never much liked him. It was clear to them that LeMond was washed up, and they hurried to pass judgment on his demise. The consensus was that he had had no business hunting during the racing season. As with his ridiculous attachment to golfing, it showed he wasn’t serious.

Meanwhile, in LeMond’s absence, two absurdly mediocre riders he could easily have crushed—Roche and the Spaniard Pedro Delgado, respectively—won the next two Tours de France. Roche never came under any serious doping suspicions, but no can deny he faced a weak field. Delgado, on the other hand, during the last week of his 1988 victory, tested positive for probenecid, a steroid masking agent. But Tour organizers let him off the hook on a technicality. The ban on probenecid was conveniently not scheduled to take effect until a week after the Tour was over; so as far the bylaws were concerned Delgado was clean. The modern doping age—in which no one inside cycling would acknowledge what everyone outside it could see—had begun.

Americans—notably the members of the 7-Eleven team—were regularly competing in the Tour de France beginning in 1986, but only one besides LeMond (the gangly Andy Hampsten) was ever deemed the slightest threat. One reason for this was that these Americans were as shocked as LeMond had been in his rookie year to discover that syringes were everywhere on the circuit. And because they could barely keep up riding “clean,” the Europeans ridiculed them, claiming that they lacked a work ethic. By the time LeMond returned to the peloton in 1989, cycling’s biggest trophy appeared as if it would never be touched by American hands again.

Americans—notably the members of the 7-Eleven team—were regularly competing in the Tour de France beginning in 1986, but only one besides LeMond (the gangly Andy Hampsten) was ever deemed the slightest threat. One reason for this was that these Americans were as shocked as LeMond had been in his rookie year to discover that syringes were everywhere on the circuit. And because they could barely keep up riding “clean,” the Europeans ridiculed them, claiming that they lacked a work ethic. By the time LeMond returned to the peloton in 1989, cycling’s biggest trophy appeared as if it would never be touched by American hands again.

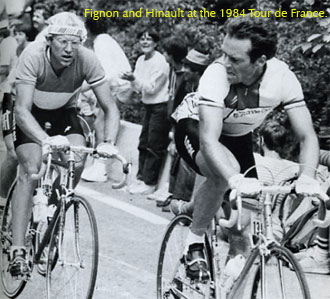

That July, Laurent Fignon, a Parisian called Le Professeur because of his granny glasses, entered the final day of the Tour with the Maillot Jaune on his back. Fignon, who had ridden to victory for Renault in 1983 and 1984, was a former teammate of LeMond and before that of Hinault, and he had apparently observed the Badger’s tactics for managing his protégé off the bike. Before the start of the last stage, Fignon congratulated LeMond on his second place finish.

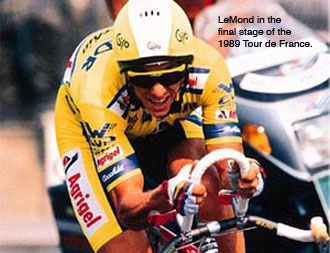

In any other year, Fignon’s transparent psych out would have been gratuitous, as it is an unspoken rule that no one attacks the yellow jersey on the final day. This is because the Tour, which always ends in Paris, traditionally winds down with a series of high-speed laps around the Champs-Élysées, which are dangerous and best left to the specialist sprinters to fight over. In 1989, however, the final stage happened to be an individual time trial, which meant that all bets were off. Still, to erase his 50 second deficit, LeMond would need to average nearly 34 mph over the 15.5 mile course. More than just an ordinary all-out effort, this would have to be the fastest recorded time trial in Tour history. Using state of the art aerodynamic gear—a teardrop helmet, solid rear wheel, a sloped bicycle frame with upturned handlebars—LeMond overtook Fignon by an eight second margin, the closest finish ever.

LeMond won the Tour again the year after, but even at the time his third victory felt like a bittersweet footnote. As awesome as his comeback had been, LeMond obviously wouldn’t reach the five-time Anquetil-Merckx-Hinault mark (worse, in the interim between his subsequent decline and Armstrong’s ascent, the Spaniard Miguel Indurain won a record five Tours in a row). LeMond can do the math, and when asked has admitted as much. Between the two he missed and the one he threw, he should have been the first cyclist—instead of Armstrong—to win six Tours.

In 1994, the last season LeMond rode professionally, he was already suffering from “mitochondrial myopathy, a degenerative muscle disease that drained his strength and may well have been caused by passive doping,” writes David Walsh in his new book, From Lance to Landis: Inside the American Doping Controversy at the Tour de France—an indispensable read for anyone who cares about pro cycling. “Passive doping” refers to the theory—supported by medical research—that “clean” riders like LeMond, by overcompensating to keep up with the dopers, do irreparable harm to their health.

In 1994, the last season LeMond rode professionally, he was already suffering from “mitochondrial myopathy, a degenerative muscle disease that drained his strength and may well have been caused by passive doping,” writes David Walsh in his new book, From Lance to Landis: Inside the American Doping Controversy at the Tour de France—an indispensable read for anyone who cares about pro cycling. “Passive doping” refers to the theory—supported by medical research—that “clean” riders like LeMond, by overcompensating to keep up with the dopers, do irreparable harm to their health.

As the conclusion to an improbable comeback, LeMond’s fade into illness makes for a decidedly less happy ending than Lance Armstrong’s seven Tours, never mind his beating testicular cancer. But as Walsh argues, there is overwhelming circumstantial evidence to suggest that Armstrong is not the miracle man he claims to be. Indeed, there is reason to believe that doping was the cause of his cancer in the first place.

Walsh lays waste to the favorite chestnuts of Armstrong mythology, including the laughable fallacy that he possesses, literally, a “big heart” or the idea that his comeback successes can be attributed to weight he lost while battling cancer (he didn’t lose any). Whereas LeMond won his third Tour decisively, Armstrong took 36th place in his third, almost an hour and a half behind the yellow jersey. That, by the way, was the first Tour Armstrong was able to even finish; before that, he had always crumbled in the mountains, where the Tour is usually decided. In Walsh’s view, the pre-cancerous Armstrong was a solid all-around rider, but a below average climber—not the stuff of a Tour champion.

Tell that to those Americans (the 2004 Democratic presidential nominee among them) who proudly wear their yellow LIVESTRONG bracelets. Gaudy numbers aside, Armstrong boasts the kind of hardscrabble Texas upbringing that appeals to casual Americans sports fans and the denizens of Madison Avenue, neither of whom have an appreciation for cycling, but whom can recognize Horatio Alger when they see him.

The time has come to reevaluate LeMond’s standing in cycling history. In retrospect the cheeks of that “boyish” face were always scarred by acne pits, the brow was prematurely lined, and the jowled demeanor mysteriously weary for someone his age. Is it too simple to say that we now understand why?

Doping is possibly as rampant in bicycle racing as in any other professional sport. This may be come as a surprise to American baseball fans, but truly cycling has long been a trendsetter in jockdrug fashions. The very same greenies, for example, that players surreptitiously palmed in the dugouts of the 1960s and 1970s were during the same period administered by cycling team doctors and soigneurs, who stuffed them in the lunch bags. Notoriously, during the 1967 Tour de France, Englishman Tom Simpson collapsed under a hot sun on the climb up Mont Ventoux and died, purportedly from “exhaustion.” No one inside cycling blinked when an autopsy found amphetamines in his system, mixed with alcohol from the night before.

Doping is possibly as rampant in bicycle racing as in any other professional sport. This may be come as a surprise to American baseball fans, but truly cycling has long been a trendsetter in jockdrug fashions. The very same greenies, for example, that players surreptitiously palmed in the dugouts of the 1960s and 1970s were during the same period administered by cycling team doctors and soigneurs, who stuffed them in the lunch bags. Notoriously, during the 1967 Tour de France, Englishman Tom Simpson collapsed under a hot sun on the climb up Mont Ventoux and died, purportedly from “exhaustion.” No one inside cycling blinked when an autopsy found amphetamines in his system, mixed with alcohol from the night before.

The 94th Tour de France begins today and Floyd Landis, who is still awaiting a ruling, will not be there. Rather, he will spend this July on a book tour, promoting Positively False, a title presumably not intended to send mixed signals. Should Landis be found guilty he would become the first Tour de France champion to be stripped of his title, but not exactly the first one who had it coming. Just a week after Landis’s hearing wrapped up, Bjarne Riis, a former Danish pro who won the 1996 Tour, admitted to using a range of banned substances when he competed. Riis’s belated mea culpa arrived, not coincidentally, a day after two of his ex-teammates had acknowledged doping. It is increasingly difficult to remember that, as Emma O’Reilly, a former soigneur for Armstrong, says, “Once upon a time you could do [the Tour] on spaghetti and water, but it’s become impossible now.”

Was it ever possible? By association alone, Walsh implicates a number of the sport’s luminaries, including Merckx, whom personally introduced Armstrong to the infamous trainer and doping apologist, Dr. Michele Ferrari. “Landis only did what he had to do. I wasn’t with him, but for me, it’s just a big mistake,” Merckx has said. Coming from a five-time Tour winner, it’s a disappointingly ambiguous statement, and at the very least hardly qualifies as an anti-doping stance.

For half a century now pro cycling has had a drug problem, and since the mid 1990s that problem has accelerated exponentially—much like the average speeds of the peloton—largely due to the widespread use of r-EPO, a synthetic hormone purchasable without a prescription in Switzerland. The conspiracy—there is no other word—to deny the vast extent of r-EPO’s abuse, together with a host of other laboratory concoctions, will continue unabated so long as cycling’s culture of silence also endures.

In more ways than one, Greg LeMond has courageously defied the social convention of keeping quiet about anything shameful. Although the record books tell a different story, the Tour de France has had no worthier champion than him.